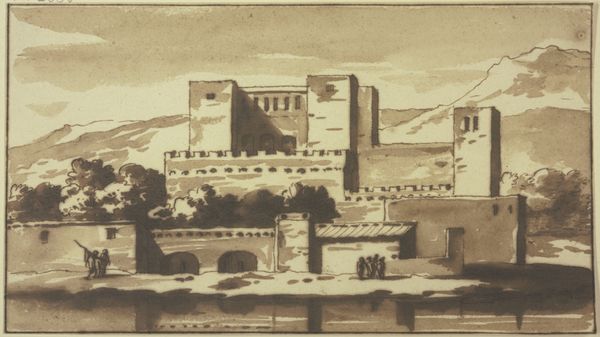

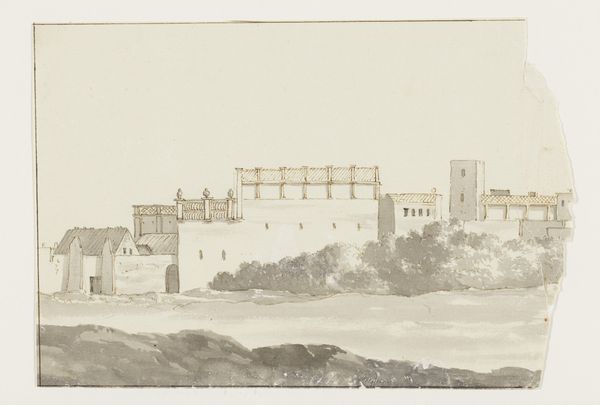

Italienisches Kloster hinter hohen Mauern, die Turmruine der Torre delle Millizie in Rom nachempfunden

0:00

0:00

drawing, paper, ink, architecture

#

drawing

#

baroque

#

landscape

#

paper

#

ink

#

14_17th-century

#

cityscape

#

architecture

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: So, this is "Italian Monastery behind High Walls, Modelled on the Tower Ruins of the Torre delle Millizie in Rome" by Jacob van der Ulft, created in ink on paper. The monochromatic color palette creates a certain austerity that I find compelling. What draws your eye when you look at this? Curator: Well, immediately, the title itself sets a historical stage. Consider the explicit reference to the Torre delle Millizie. Ulft isn’t just drawing any monastery, he's linking it directly to a potent symbol of Roman history, specifically the medieval power struggles played out in its urban fabric. It becomes less about architectural rendering, and more about historical contextualization, don't you think? Editor: Absolutely. The inclusion of the Roman ruin really contextualizes the drawing within a broader historical narrative. But is the "monastery" itself a real place, or is it just a stage for Ulft’s historical drama? Curator: That's precisely the point. Ulft is presenting an imagined reality. We, as viewers, are invited to participate in constructing meaning through the interplay between fact and fiction, reality and representation. The drawing acts as a social mirror, prompting the Dutch audience to reflect on their relationship to Italian history. Notice how the figures in the foreground are diminutive, almost like actors on a stage. It emphasizes the public role of art as both spectacle and interpreter of history. Editor: That makes so much sense! I was caught up in the architectural details. I realize now it's less about accurately portraying the monastery and more about creating a dialogue about power and history. Curator: Exactly. By placing the Dutch viewer in front of a staged Italian scene filled with social-political commentary, Ulft utilizes architecture and drawing as instruments for cultural exchange. It leaves one questioning how places we may never have seen or people we've never met can affect how we understand our own history. Editor: I never would have looked at this drawing in that light. Thanks for making me question my assumptions. Curator: It works the other way too. I always come away from these conversations with a fresh pair of eyes, questioning what narratives museums such as the Städel create by curating such artwork.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.