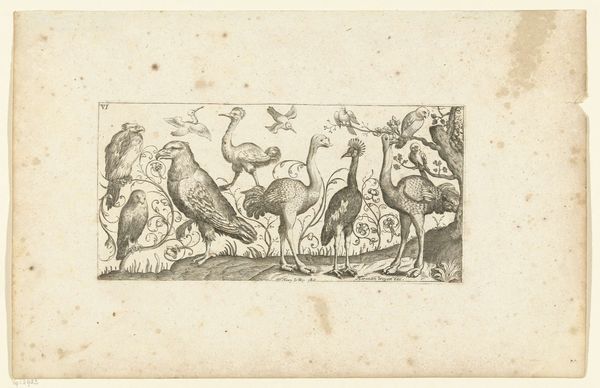

print, engraving

# print

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

italian-renaissance

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 68 mm, width 83 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Welcome! We’re standing before Christoph Jamnitzer’s "Liggend ovaal met putto," an engraving likely created between 1573 and 1610, during the late Renaissance. Editor: That's quite an odd creature depicted! It feels so unsettling. The contorted posture and the… hybrid form really disturb the balance of the landscape. Curator: Indeed. The artist's family, known for metalworking and goldsmithing, certainly influenced his printmaking, which blends Italian Renaissance themes with elements of the German Renaissance. I imagine the production process—the physical labor of carving those fine lines into a metal plate, printing many copies, would've been both intensive and valuable for wider consumption. Editor: Look at the lines; how meticulously the light falls to define form, especially those wings! There’s a tension, though—the fine detail clashes with that monstrous figure's awkward pose and peculiar morphology. Curator: Consider the period, though: The tension itself reveals an ambivalence about nature and the human form at this historical point. Prints like these democratized art production but also became subject to social and moral debates. Editor: And what does that say about the intention to replicate a so called mistake of the “mother” creator of everything? I want to draw your attention to the setting too: the flat, almost theatrical backdrop. It confines the subject into an unreal plane. Curator: The artist deliberately constructs artifice by manipulating perception. Think about the paper, and its own industrial lineage at the time... Each element here involved extraction, labor, exchange. Editor: A formal puzzle that seems to revel in disruption. Curator: An embodiment, you could say, of the shifting socio-economic landscape, imprinted and circulated through physical material and toil. The labor embedded is undeniable. Editor: I leave more disoriented than informed—though, certainly provoked—by this unsettling composition and I encourage visitors to pause here for another minute or so. Curator: And to remember how much work was embodied in its production, and in its arrival here for your contemplation. Thank you.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.