Dimensions: image: 24.77 × 30.48 cm (9 3/4 × 12 in.) sheet: 27.94 × 35.56 cm (11 × 14 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

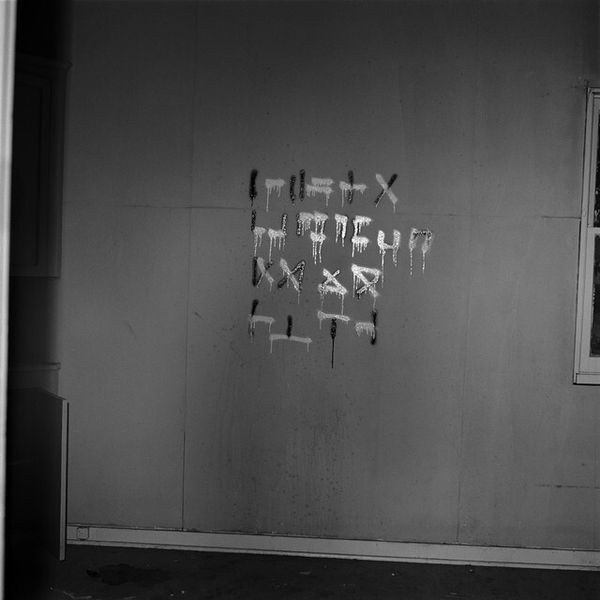

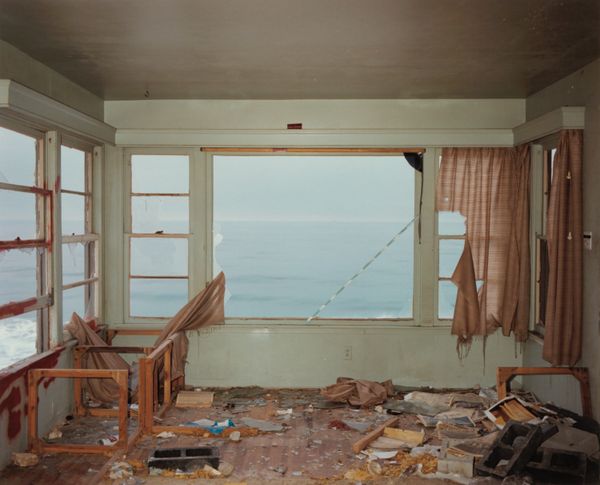

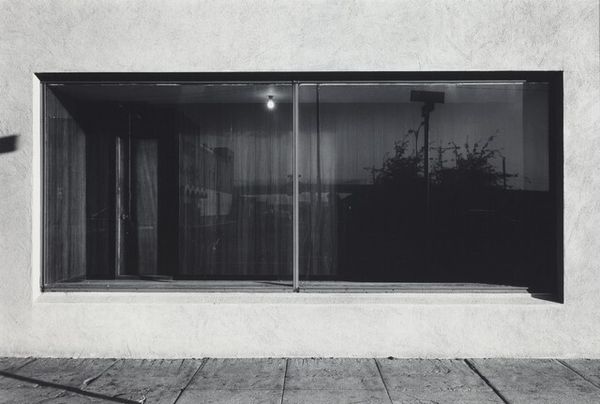

Curator: Let’s discuss John Divola's "Zuma #82," a mixed-media photograph from 1978. My initial reaction is how barren and desolate it feels, and what might have motivated him to stage a site like this one for artistic purposes. Editor: Barren is a great word. Immediately, I notice the stark contrast between the white walls marked with graffiti and the littered floor. It has a definite post-apocalyptic vibe, almost like evidence of a forgotten community, a hidden critique on the artifice of space and the performativity within its staged decay. Curator: Divola was indeed interested in the intersection of photography, performance, and the socio-political landscape of Southern California. This was part of a series shot in abandoned houses near Zuma Beach. He would break in, create temporary interventions using spray paint and other materials found on site, and then photograph the results. Editor: The choice of abandoned spaces is so pointed, too. It’s a visual representation of social abandonment and raises interesting questions about land use, housing crises, and systemic inequalities. What’s left behind becomes a canvas. Curator: Precisely. These aren't simply derelict spaces, they become sites of artistic intervention and documentation, raising the issue of whose stories and lives are considered valuable enough to be preserved and remembered. And he seems to make commentary on a very strong aesthetic and historical art conversation through that space. Editor: Yes! I see echoes of land art, where the artist engages directly with the environment, and the Situationist International, which disrupted urban landscapes through performative acts, revealing underlying social and political tensions. Here, graffiti becomes a gesture, a reclaiming of spaces deemed worthless. The red line cutting horizontally across the walls acts almost as a border, calling the segregation of socio-political landscapes to our attention, too. Curator: The location is key. Zuma Beach is known for its affluence and its presence in media and entertainment culture. But this series reveals another layer – a reminder that not all of Southern California enjoys such idealized representation, making us reconsider the idealized cultural symbols we are confronted with. Editor: Exactly. In this context, Divola's work isn't just about aesthetics; it's about activating a dialogue. What do we choose to see, what do we ignore, and how do spaces reflect larger socio-political realities? It's quite the wake-up call, reframing how we view landscape photography and its role in revealing uncomfortable truths about a specific time and context.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.