Copyright: Public domain

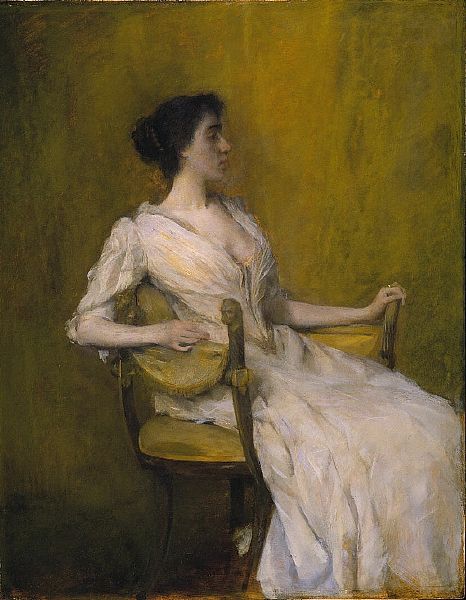

Curator: This is Frank Benson’s 1893 oil painting, “Firelight”. Editor: Oh, the mood is striking—that hazy, amber glow creates such intimacy. I feel like I'm intruding on a private moment, with the weight of expectation lingering in the air. Curator: Exactly, Benson’s process involved building up layers of impasto, focusing on the interplay between the figure's form and the firelight source, resulting in a soft yet vibrant surface. Consider the sheer labor required to capture that effect, from mixing pigments to layering the paint itself. Editor: That layering technique you've indicated almost obfuscates the woman's identity and I believe, whether consciously or not, Benson makes a broader statement here. How often were women like her rendered primarily in terms of light, as decoration? And this ghostly presence behind her only heightens this dynamic, suggesting all that society demanded she repress or sacrifice in service to it. Curator: The creation of a piece like this required skilled craftsmanship, as did the tailoring of her dress, another form of labor involved in the artwork's social circulation. The material cost involved reflects a world of wealthy patronage and elite commissioning, which can speak volumes about who controls cultural production. Editor: Indeed, that costume she’s wearing – a cage she’s donned for male consumption, constructed specifically for that exchange! But there is power here too. Looking at her poised stillness, she becomes not only a representation but a figure in resistance – against what, exactly? Against those limiting forces, and against those structures that denied her depth. She’s holding the fire inside. Curator: True enough. I think there's a genuine connection between Benson's artistic labour and the figure he represents – his engagement with material processes mirrored her own constraints, the shaping of her identity. It’s fascinating. Editor: It is. Looking closely makes you wonder whether that ‘firelight’ she basks under ultimately frees or imprisons. A challenging commentary even now, some hundred years later.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.