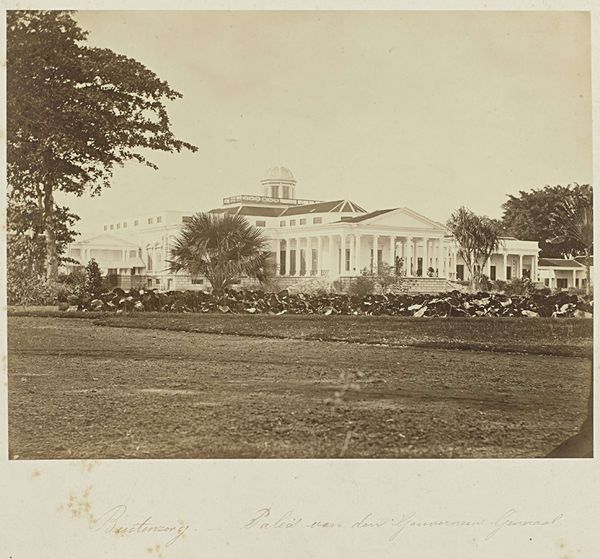

![[Government House, Allahabad] by John Constantine Stanley](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fd2w8kbdekdi1gv.cloudfront.net%2FeyJidWNrZXQiOiAiYXJ0ZXJhLWltYWdlcy1idWNrZXQiLCAia2V5IjogImFydHdvcmtzL2RlYWUyMWQxLWVjZWQtNGE5OC1iYzYyLWZiNGIzYmUzM2Y3MS9kZWFlMjFkMS1lY2VkLTRhOTgtYmM2Mi1mYjRiM2JlMzNmNzFfZnVsbC5qcGciLCAiZWRpdHMiOiB7InJlc2l6ZSI6IHsid2lkdGgiOiAxOTIwLCAiaGVpZ2h0IjogMTkyMCwgImZpdCI6ICJpbnNpZGUifX19&w=3840&q=75)

daguerreotype, photography, architecture

#

landscape

#

daguerreotype

#

photography

#

orientalism

#

architecture

Dimensions: Image: 7.1 x 7.6 cm (2 13/16 x 3 in.) Mount: 33 x 26 cm (13 x 10 1/4 in.)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: This is "[Government House, Allahabad]," a daguerreotype created by John Constantine Stanley in 1858. It's currently held in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Editor: There’s a somber, faded beauty to it. The sepia tones create a strong sense of history and almost feel like we’re peering through time. It’s austere, yet there’s a distinct aura of colonial power emanating from that architecture. Curator: Indeed. Daguerreotypes were a relatively new medium at the time, and their creation involved meticulously polishing a silver-plated copper sheet, sensitizing it with chemicals, exposing it in a camera, and then developing the image using mercury fumes. Consider the labor and skill needed! It challenges any easy distinction between art and industry. Editor: Absolutely. And looking at the social context, this image was produced during a period of intense colonial control in India. Government House represents the physical embodiment of British authority, standing amidst a landscape subtly shaped by imperial intervention. It's not just a picture of a building; it's a document of dominance. The architecture has classical elements yet sits distinctly in this Indian context; this tension speaks volumes about the period. Curator: Exactly. The material choices and the very act of photographing and circulating such an image played a role in constructing and reinforcing imperial narratives. Note, for instance, how the framing centers the architecture; any people are merely diminutive, faceless details. The process and its result reflect the dynamics of power at play. Editor: That’s a crucial point. Who gets represented, how, and for what purpose are all vital questions. It invites critical analysis of colonial photography's role in shaping perceptions and justifying political control. The gardens are carefully manicured, a symbolic reshaping of nature under imperial design. Curator: The very act of creating this photograph, employing imported technology and chemicals, underlines the economic imbalances inherent in colonialism. Each step in the process implicates the social relations of production and consumption. Editor: Seeing it now, after reflecting, I still sense an atmosphere, a strange disquiet amidst the structured composition. But I'm much more aware of the story behind that initial impression now. Curator: I think by viewing the layers, material and contextual, we are more prepared to engage with images like this thoughtfully and responsibly.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.