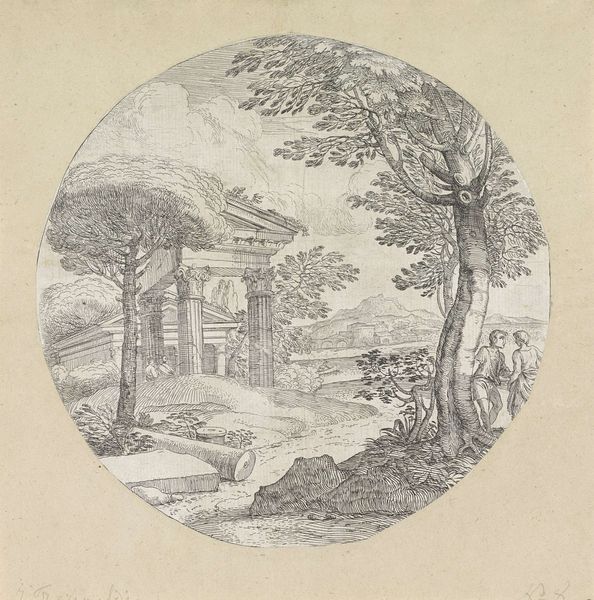

Dimensions: height 124 mm, width 127 mm, diameter 105 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Immediately striking—it’s almost ghostly, like a faded memory rendered in pencil. There’s a hazy dreaminess to this landscape. Editor: Indeed. This is Richard Wilson's "Italian Landscape with Two Figures in a Park," dating back to approximately 1754 to 1756. He employs pencil on paper, using the circular format often associated with studies or preliminary sketches. I see in its careful linework the burgeoning ideas around picturesque beauty. Curator: Picturesque, certainly. It evokes that curated naturalness, and you see how the different densities of pencil create such atmospheric depth. Think about the lead and paper qualities Wilson had to manipulate to arrive at that fogginess—a tangible texture shaped by his technique. Editor: And what kind of naturalism are we really talking about when Italian landscapes themselves became a commodity viewed through the lenses of wealthy patrons? Consider, also, the lives not represented—the labourers who toiled on these estates enabling leisurely strolls for the moneyed class. Wilson benefits directly from such inequities. Curator: True. I am also fascinated by the layering—how he builds up the forms using a limited range of tones. We see evidence of repeated lines, testing and refining his vision of an idealized space; we gain access to a mind at work. How deliberate are the tree canopies rendered by this laborious creation? Editor: These landscapes are rarely benign. They project social and political ideologies. The placement of the two figures so small—dwarfed, nearly, by the vast, manicured landscape—speaks volumes about man’s perceived relationship to land and ownership, to domination over nature. The round format softens some of that narrative impact but ultimately is there for artifice. Curator: So we see a pencil landscape created as a sort of meditation on ideal space, produced from labor that's quite intense, even on such a small scale. Editor: Precisely. Wilson's landscapes reflect and construct particular social viewpoints of his era. We must critically address what visions such images perpetuate. Curator: A necessary perspective to ensure these images prompt a broader, fairer reading.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.