engraving

#

portrait

#

old engraving style

#

15_18th-century

#

line

#

genre-painting

#

history-painting

#

engraving

#

rococo

Dimensions: height 522 mm, width 350 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

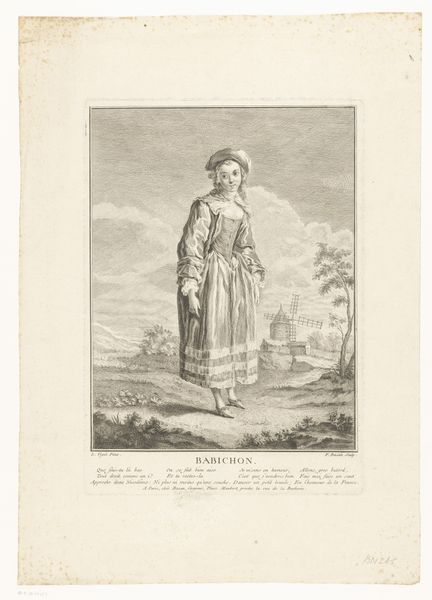

Editor: This is Jean Daullé's "Portret van Justine Favart als Bastienne" from 1754, an engraving at the Rijksmuseum. It depicts a woman in a pastoral setting, seemingly in costume. What interests me is the detail achieved through engraving. What can you tell me about it? Curator: Well, first consider the labor involved in creating this image. An engraving like this required a skilled artisan, someone deeply familiar with tools and the meticulous process of etching lines into a metal plate. It wasn’t just about artistic vision; it was about skilled craftsmanship. Editor: So, less "high art" and more... industry? Curator: Precisely. The engraver, Daullé, is reproducing another artist’s work, likely a painting. He’s acting as a conduit, using his material expertise to disseminate images to a wider audience. We need to think about the consumption of images in the 18th century. This print is a commodity, intended for a specific market. Consider the paper, the ink: these materials speak to the growing consumer culture of the time. And who was Justine Favart, what was her social position and role? Editor: Right, this image serves a purpose beyond mere aesthetics. Was this a popular method for distributing imagery? Curator: Absolutely. Engravings were a primary means of reproducing and circulating images. It’s a form of mass production, albeit on a smaller scale than we’re accustomed to today. Each line carefully etched, transferring from one surface to another, so that it might transfer again through ink to paper. It highlights not only artistry but the labor of reproducibility in the art world, it seems a way for a wider public to access a theatrical and celebrity culture. Editor: I see, so it's not just about the image itself, but about the entire material network that brought it into existence and to the public. That makes me rethink its importance entirely. Curator: Indeed. It’s a perfect example of how focusing on materials and production methods can open up new avenues for understanding art history.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.