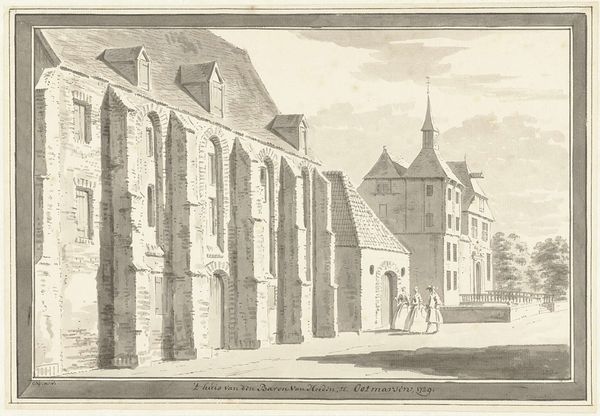

Gezicht op de abdij en het hof van Henneberg te Loosduinen 1685 - 1735

0:00

0:00

abrahamrademaker

Rijksmuseum

drawing, paper, ink

#

drawing

#

baroque

#

dutch-golden-age

#

landscape

#

paper

#

ink

#

cityscape

Dimensions: height 130 mm, width 210 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: It's a sepia-toned landscape. Stark and still, somehow. Gives me a sense of both strength and quiet solitude. Editor: That’s quite perceptive. We’re looking at "View of the Abbey and the Court of Henneberg in Loosduinen," a drawing in ink on paper. It was rendered sometime between 1685 and 1735 by Abraham Rademaker and it now resides at the Rijksmuseum. What draws me in immediately is its meticulous rendering. The attention to detail in capturing this architectural structure is really astounding. Curator: I agree. Rademaker masterfully uses the brown ink to depict texture and light. The walls look almost impenetrable and each tree and tiny window hints at stories locked inside. The visual weight conveyed feels very masculine to me, in a strange way, rooted in control and power. Do we know anything about the court and its associations? Editor: Loosduinen held particular significance, actually. This was the location where Countess Margaret of Henneberg was said to have given birth to 365 children in 1276—an origin myth designed to reinforce existing local power structures. Rademaker, by choosing to highlight the architectural space itself, visually participates in the process of creating and circulating such myths. It gives material and representational weight to these structures. Curator: Exactly. And you notice how the clouds mirror the shapes of the buildings? They are not separate from human activity; even the sky feels shaped by these buildings. The use of brown ink makes me think about age, archives, memory— all bound up within the sepia tones. It’s like he has stained the page with the weight of this local lore. Editor: It is important to also reflect upon this image from an aesthetic perspective. The Dutch Golden Age, with its embrace of realism, aimed to reflect the world with detailed precision, and as this imagery helped forge national identity. This image offers not merely a building, but participates in that artistic and social construction of reality. Curator: And to what end, precisely? Were these images neutral? Who benefitted from constructing this imagery and embedding these myths into public consciousness? It strikes me that it almost doesn't matter what actually occurred—only that the symbolic impact reinforces specific social relationships, such as fealty and patriarchy. Editor: Definitely, because those are exactly the kind of questions that we should be asking ourselves, questions this image almost implicitly poses about cultural memory and how landscapes themselves carry meanings shaped by us.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.