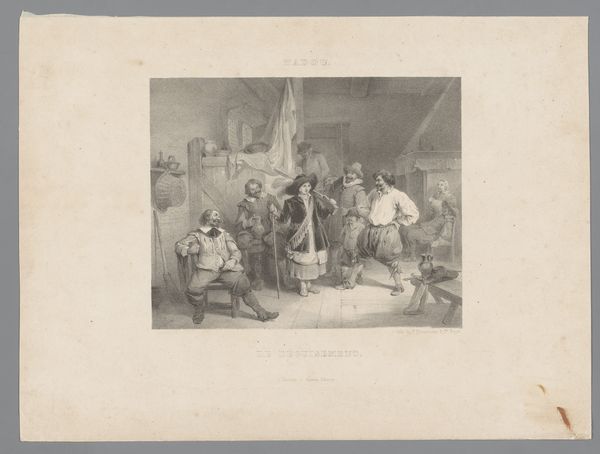

print, engraving

#

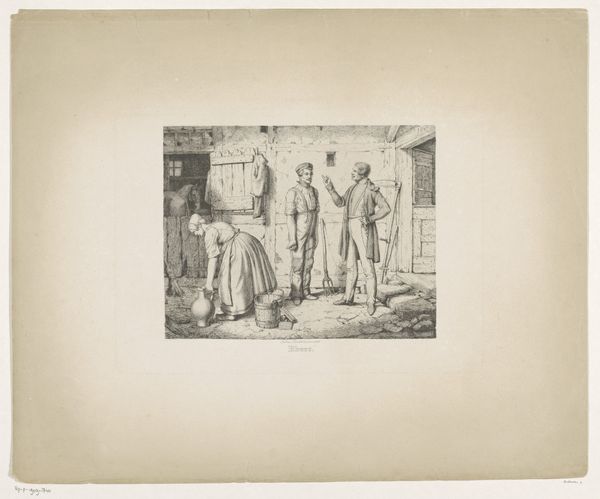

pencil drawn

#

light pencil work

#

narrative-art

# print

#

pencil sketch

#

old engraving style

#

romanticism

#

genre-painting

#

engraving

#

monochrome

Dimensions: height 285 mm, width 405 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

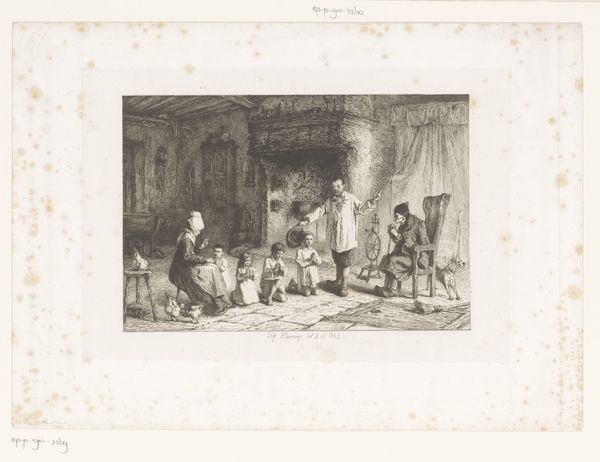

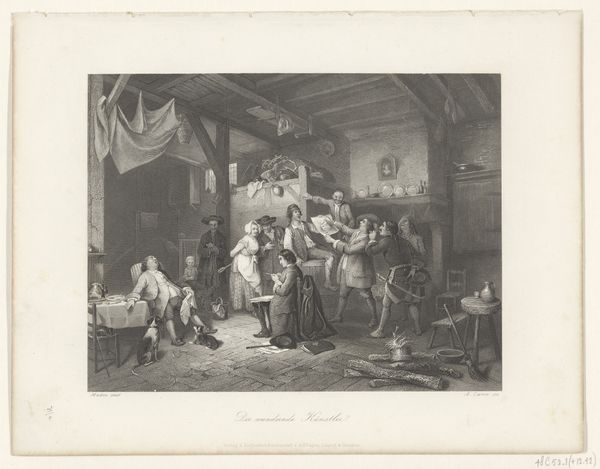

Curator: This is "Man toont priester een prent met Napoleon Bonaparte," or "Man Shows Priest a Print of Napoleon Bonaparte," created in 1834 by Hippolyte Bellangé. The piece is currently held in the Rijksmuseum collection and is an engraving. It strikes me immediately as a carefully constructed tableau. Editor: A tableau indeed! The crisp monochrome amplifies the narrative focus. Light and shadow create such clear delineation, directing the eye, a story unfolding in each face. But, what can you tell us about its creation and purpose in society? Curator: Bellangé, deeply engaged with the political landscape of post-Napoleonic France, offers a peek into how revolutionary figures were digested at the level of local life. The work highlights how symbols become embedded in a cultural and economic landscape. Consider the materials; prints like this would have been mass-produced for circulation. Editor: Quite so. Focusing on the form, the diagonal created by the man’s arm gestures sharply toward the Bonaparte print above the fireplace. Note the seated priest's closed posture. Do you see a silent resistance embodied in his demeanor? The faces of the children too - wonder mixed with skepticism. A dynamic visual interplay of conflicting emotions. Curator: Precisely. And beyond emotions, look at the materiality of this exchange. The print itself becomes a commodity; a representation that's both propaganda and folk art. This piece asks us to consider not just what the image portrays, but what it does; its utility. How did popular imagery function to form perceptions about power after Napoleon? How did individuals gain and spread access to these representations of power? Editor: Absolutely. And consider how skillfully Bellangé deploys a simple medium like engraving to weave complex webs of societal critique. The visual tension created through posture and expression reinforces his message, but the question remains of his relationship to that message: Is this satire? An homage? I can’t quite settle. Curator: Ambiguity is part of the charm and a nod to the contentious environment during the post-revolution. Editor: Indeed, it’s that visual tension and open-ended interpretation that render this work such a powerful object of study, one that persists.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.