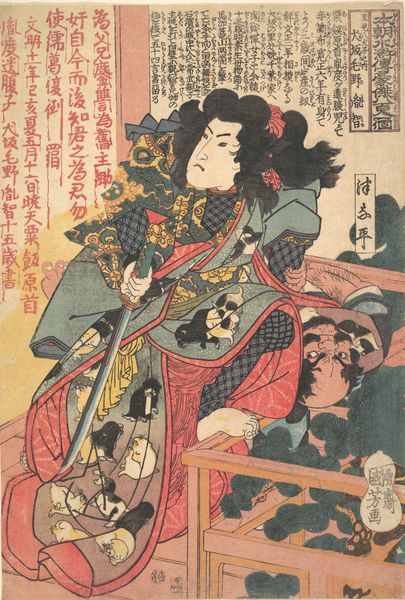

Bai Sheng (Hakujisso Hakusho), from the series "One Hundred and Eight Heroes of the Popular Water Margin (Tsuzoku Suikoden goketsu hyakuhachinin no hitori)" c. 1827 - 1830

0:00

0:00

print, woodblock-print

#

portrait

#

narrative-art

# print

#

asian-art

#

ukiyo-e

#

japan

#

figuration

#

woodblock-print

#

naive art

#

orientalism

#

tattoo art

#

history-painting

#

erotic-art

Dimensions: 39.3 × 26.9 cm (15 1/2 × 10 9/16 in.)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Allow me to introduce "Bai Sheng (Hakujisso Hakusho)," a woodblock print from the series "One Hundred and Eight Heroes of the Popular Water Margin" by Utagawa Kuniyoshi, created around 1827 to 1830. Editor: Woah! That's a wild first impression. It's a chaotic explosion of tattoos, snakes, and pure rage. Sort of makes you sweat just looking at it. Curator: Indeed. Kuniyoshi was known for his dynamic compositions and vivid depictions of historical and mythical figures. Notice the intricate linework of the tattoos. They speak to the societal role of body art, not merely as decoration, but as markers of identity and rebellion. And then there are all those snakes, actively wrapping themselves into the fight. Editor: Those snakes are wonderfully unsettling. I’m guessing that they have an intense symbolic significance, perhaps cunning or temptation? I mean, they give the piece a raw, visceral energy, like a heavy metal album cover. And look at the figures themselves! It’s interesting how Kuniyoshi uses caricature, almost humorously grotesque expressions, during what's ostensibly a violent clash. The dude being crushed under the table seems particularly displeased. Curator: Absolutely. It highlights Kuniyoshi's skillful balance between dramatic narrative and accessibility for a wide audience. The printmaking process itself, requiring careful carving and multiple blocks for each color, democratized art consumption in 19th-century Japan. Editor: True. Thinking about that painstaking process is amazing, knowing how the imagery feels so… immediate. It really underscores how ukiyo-e prints made these epic stories accessible outside the elite circles. Curator: Considering the source material in Chinese literature and Kuniyoshi’s context in Edo-period Japan provides layers to interpretation of this chaotic scene of the tattooed hero, caught in this tense interaction. The dynamic use of serpentine lines, the detail of the hero’s musculature…it all culminates in one of the strongest examples of ukiyo-e that can be found at The Art Institute of Chicago. Editor: I love that the artist isn’t afraid to be playful with what's essentially a story of conflict. It challenges the conventional “heroic” presentation, making it, paradoxically, more human. Gives us some things to reflect on about power, rebellion, and the narratives we construct around both.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.