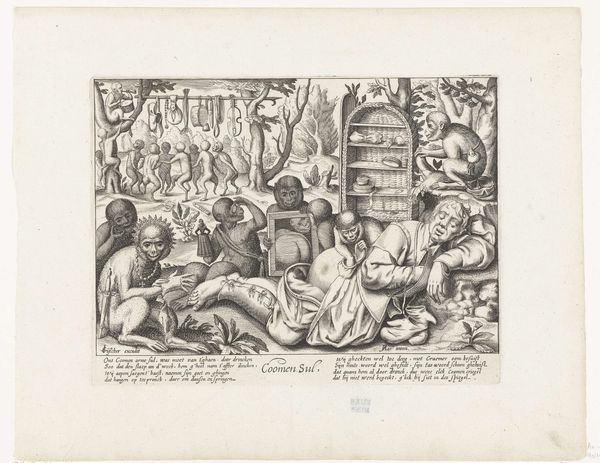

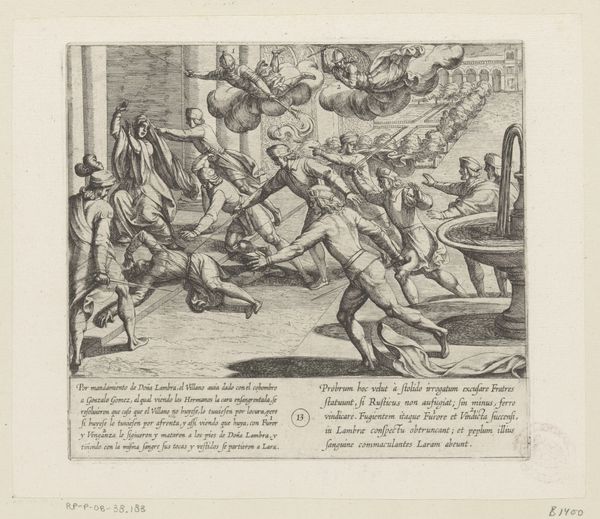

print, engraving

#

portrait

# print

#

old engraving style

#

figuration

#

islamic-art

#

genre-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 129 mm, width 167 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Let's pause here in front of this intriguing print titled "Kleding van bewoners van India," created in 1672. Editor: My first impression is how delicate the lines are, yet there's a certain stiffness to the figures. It feels both informative and slightly distanced from its subject. Almost clinical? Curator: As an engraving, the piece excels in rendering texture; you can practically feel the weight of the fabrics, and imagine the process it would have taken. The material is so clearly the focus, from paper to the artist’s mark itself! I wonder what paper they were using then, or how accessible printmaking was for the common person, if at all... Editor: That stiffness might come from the intention, which is more documentary than emotive. These aren't individual portraits in the traditional sense. They are studies of dress, attempts to record and categorize through line and form. The clothes define the man. They denote status and maybe trade, the swaggering curves and adornments speaking louder than mere material function... Curator: Absolutely. Consider, too, the broader context of its production. While we label the artist anonymous, the print inevitably bears the biases of its time. Who commissioned this work, and what purposes did it serve to represent foreign populations and the culture and manufacturing that surrounded this sort of opulence and regalia? Were these prints purely educational tools, or something else, serving a kind of cultural fetishization, that now adorn museum walls? Editor: Right. These weren't passive representations but active tools in constructing a European understanding of India, filtering lived reality through a specific lens—perhaps for trading purposes or maybe for military dominance. It makes one wonder about labor: where the inks and the fabrics are coming from, what that global footprint actually is... It also shows how quickly visual modes are taken and copied, perhaps garbled with distance and memory. Curator: Thinking of our present day, with a critical consciousness like that, reveals the distance but hopefully not disconnects from human history—and perhaps, also, our role in consumption and creation in a society, with more ethical implications for us all. Editor: Indeed. A detailed observation, it may invite conversations far deeper than simple, observational aesthetics.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.