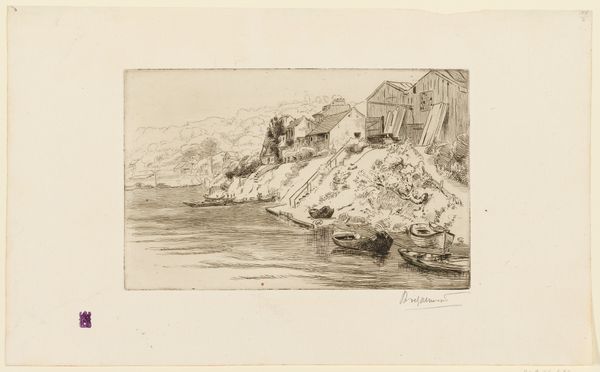

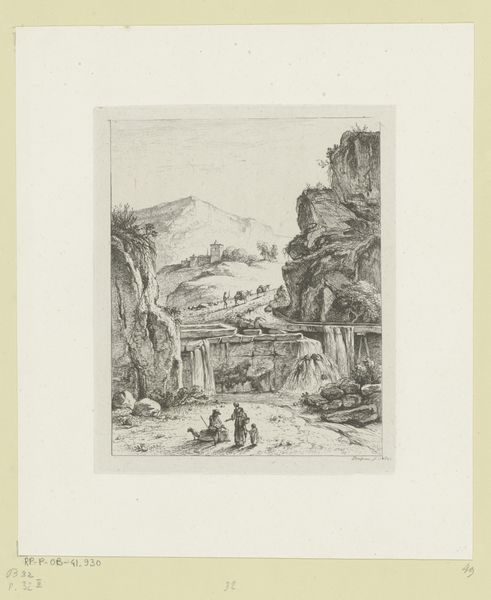

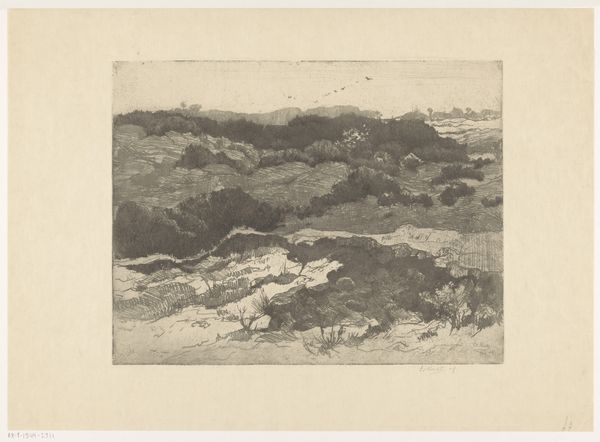

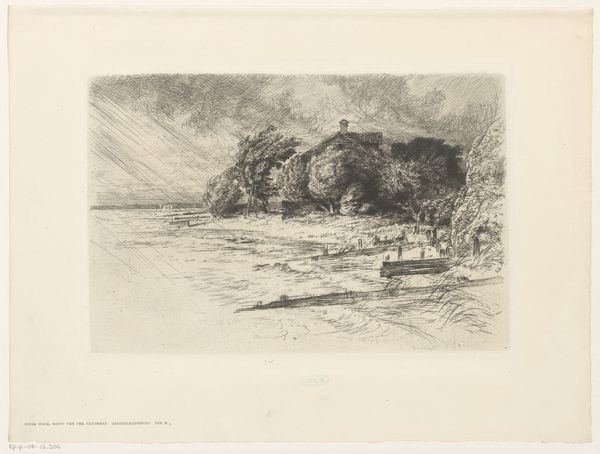

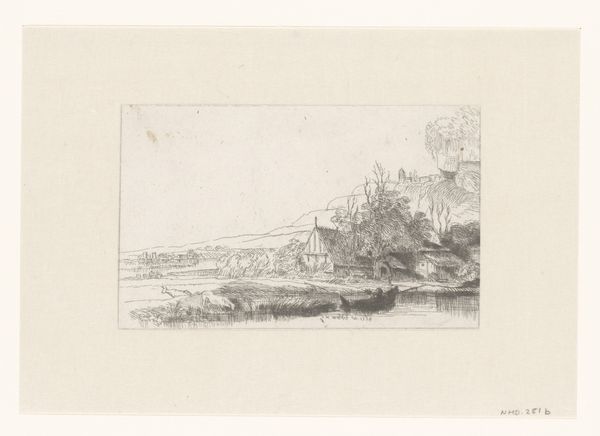

print, etching

#

pencil drawn

#

light pencil work

#

ink paper printed

# print

#

etching

#

pencil sketch

#

landscape

#

realism

Dimensions: height 235 mm, width 321 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Welcome. This print, an etching in ink on paper, is titled "Cattle Resting near a Ruin" by Karel Theodoor Hippert, likely created between 1849 and 1910. Editor: It's strikingly delicate. The light pencil work, particularly the landscape, creates this almost dreamlike stillness around figures who seem suspended in time amid the decaying architecture. Curator: Precisely. The scene presents a pastoral idyll juxtaposed with the remnants of civilization. Consider how ruins served as potent symbols in the 19th century. They represented the transience of power, the cyclical nature of history, and, in this context, perhaps even the decline of agricultural societies under the burgeoning wave of industrialization. Editor: That ruin speaks to something deeper. The method itself, etching, feels quite deliberate. Each line bitten into the plate is then reproduced; there’s this sense of imposed order, even though the lines appear spontaneous. I wonder, too, about Hippert's intentions. Was he sentimentalizing rural labor or critiquing encroaching urban life? Curator: It is likely more complicated than just nostalgia or critique. The late 19th century was marked by enormous shifts in art production. The art market and institutions were expanding, and this piece reflects a specific strand of Realism that often romanticized peasant life while being patronized by a bourgeois class seeking picturesque escapes. Editor: True, but the material execution cannot be divorced from that societal reality. The labor involved in creating such a detailed print, the specific skill set required – that's equally integral. What kind of workshop produced this, and for whom? Were these widely circulated? Curator: Records indicate Hippert often created prints to be included in portfolios aimed at amateur artists and collectors interested in landscape and genre scenes. They would have been a relatively affordable way to access "high art" for a wider segment of the middle class. Editor: It brings the focus back to this beautiful rendering and composition – how its production and consumption are undeniably social processes tied directly to shifts in class, taste, and technological changes of the era. Curator: Indeed. We can analyze the scene and style through its relationship to broader socio-political changes, connecting aesthetic choices to the social function of art in the late 19th century. Editor: It really showcases how much context transforms even the simplest of landscapes. You move away appreciating technique toward something deeply embedded within cultural and economic networks.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.