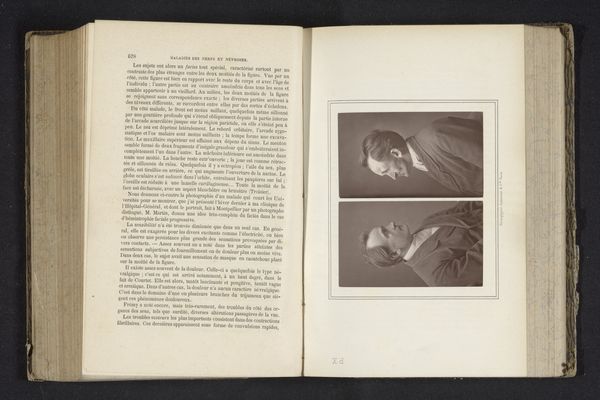

photography, gelatin-silver-print

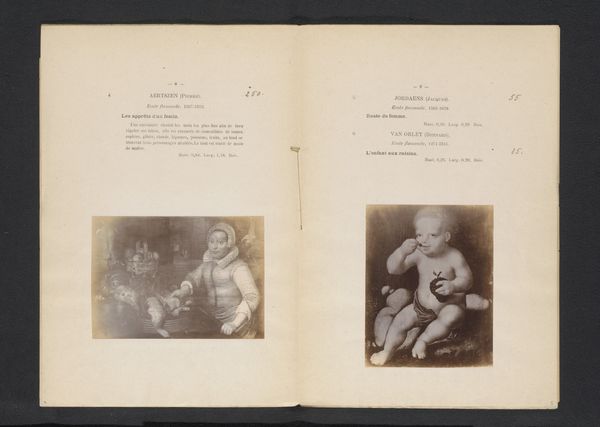

#

portrait

#

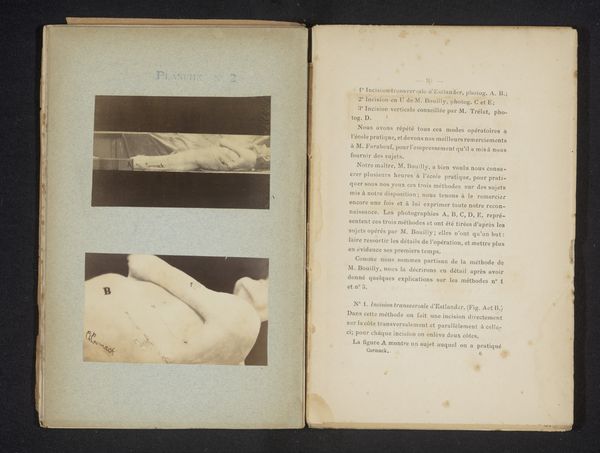

photography

#

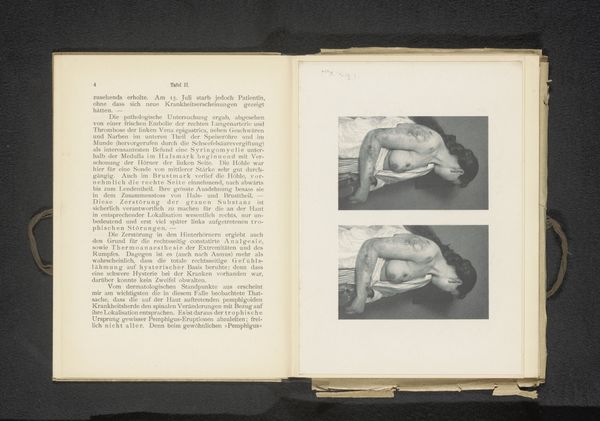

gelatin-silver-print

#

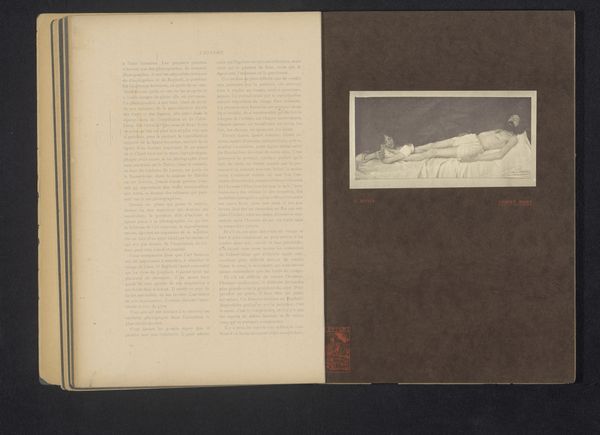

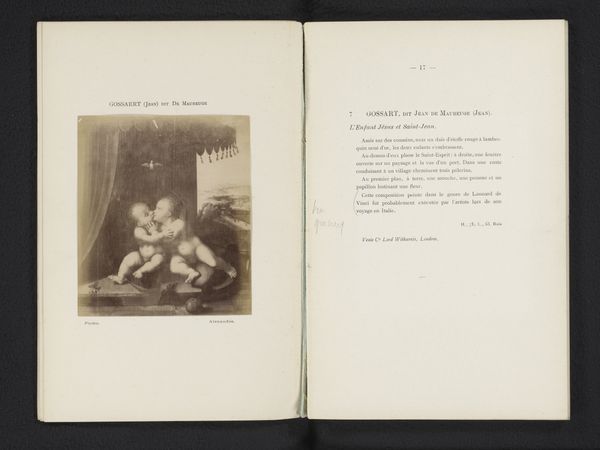

history-painting

#

academic-art

#

nude

#

modernism

Dimensions: height 109 mm, width 137 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: I’d like to introduce you to "Mannenlichaam met hechtingen onder de borst", which translates to "Male body with sutures under the breast". This gelatin-silver print, taken sometime before 1885, is quite the find. Editor: My immediate impression is one of starkness. It’s not just the subject matter, but the way the photograph confronts you. There's a sense of… clinical detachment that is at once fascinating and disturbing. Curator: Detachment, yes, it's certainly present. Given the historical context—think of 19th-century medical photography and the shift toward empirical observation—it becomes clear why Cormack adopted a certain unemotional recording of a human subject prepared for surgery. It speaks to a broader theme of the time: humankind subjected to the emerging techniques of scientific progress. Editor: Precisely. And those sutures, highlighted against the skin, carry so much symbolic weight. They're marks of vulnerability, of intervention, a potent visual metaphor for the precariousness of life. You could argue that these surgical interventions mirror a wider societal attempt to suture wounds—literal or otherwise. Curator: Absolutely. The image is loaded with this feeling that society is trying to stitch things together; bodies, countries, political ideologies... And photography itself, a medium on the rise at this period, also starts to resemble the empirical way wounds are described and classified. The gaze feels like a clinical observation. It makes one think of those early history-painting styles. Editor: Exactly. What strikes me is how the subject, despite being the focus, becomes almost secondary to the 'procedure'. It makes me wonder, in what ways does society prioritize advancement, innovation, and scientific inquiry over human agency, feelings, and dignity? Curator: That's where the modernist lens allows one to read more contemporary concerns within it. I guess every symbol we uncover carries as many questions about our world than it ever does about the period in which this photograph was taken. Editor: It's a visual probe that resonates even now. Thanks for guiding me. Curator: The pleasure was all mine. What better thing is there than unveiling the deeper scars of images like this?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.