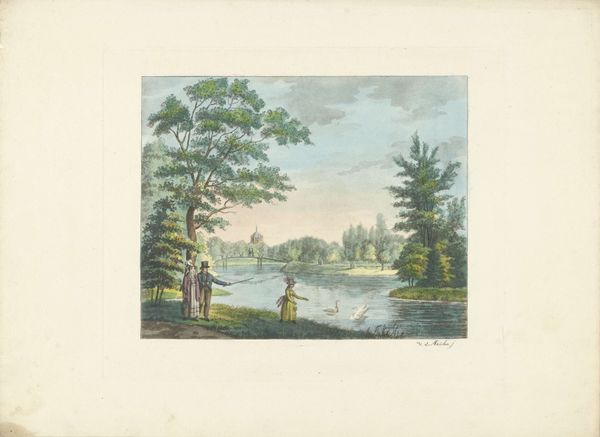

drawing, lithograph, painting, print, paper, watercolor

#

drawing

#

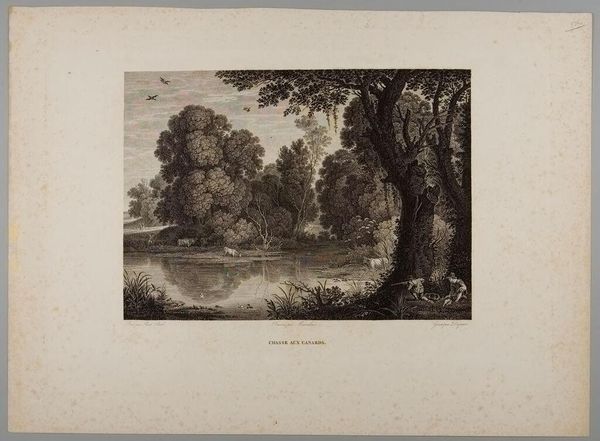

lithograph

#

painting

# print

#

landscape

#

paper

#

watercolor

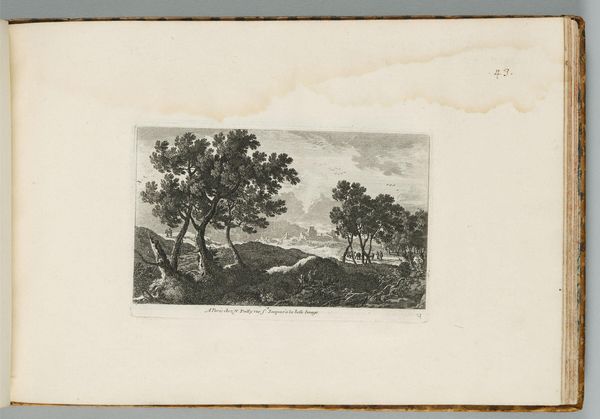

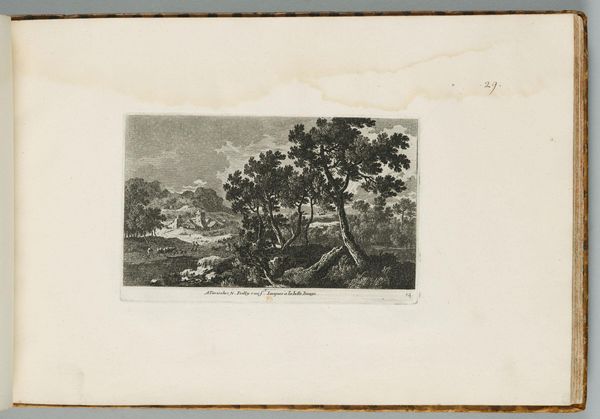

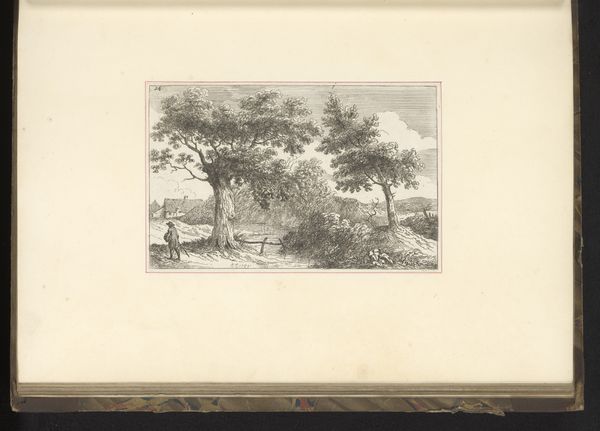

Dimensions: 79 × 108 mm (image); 141 × 195 mm (sheet)

Copyright: Public Domain

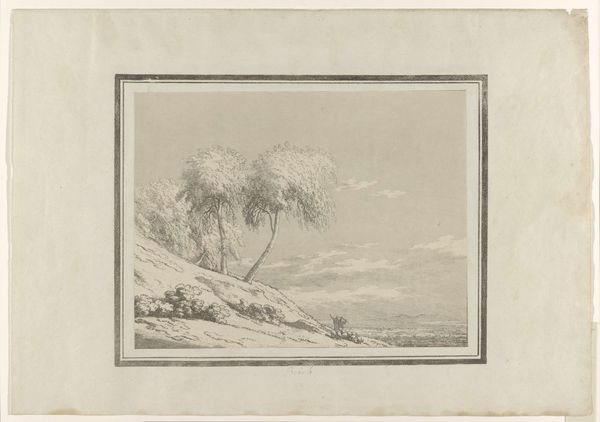

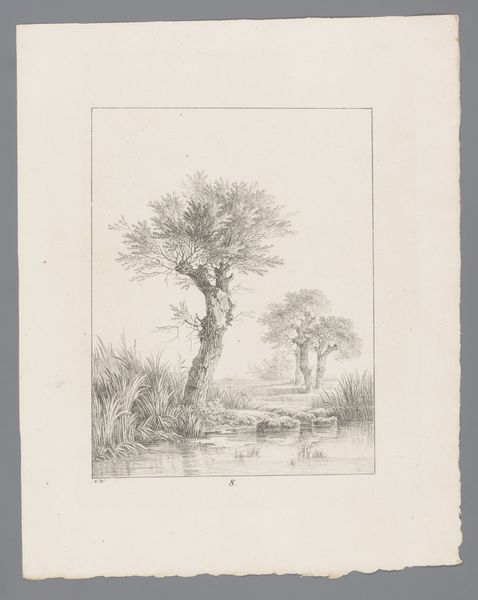

Curator: We are looking at "Landscape: River and Hills" by Victor-René Garson, housed here at The Art Institute of Chicago. It's undated, but its style suggests it was created in the late 18th or early 19th century, rendered in watercolor, drawing, and lithographic techniques on paper. What's your immediate take on it? Editor: It has a feeling of almost studied tranquility. It's pleasingly balanced and pastoral, a little idealized maybe, but still charmingly bucolic in its sentiment. It has a quietness that makes me wonder who exactly gets to have that quietness in a period defined by major historical changes? Curator: The presence of the figures is important here. Those relaxing by the riverside, along with the lone figure on the right bank—they introduce a human element that emphasizes the natural world as a backdrop for human activity and, to some extent, reinforces ideas about property and leisure. What about that iconic central tree? Editor: The tree anchors the scene and maybe symbolizes resilience and the passage of time. In a way, trees have served that way for so long in Western painting, representing everything from life cycles to knowledge itself. The winding river creates this lovely continuous flow from the figures, past the solitary one, and through the hills, offering an invitation into a calm space. But I also see this calm as constructed. Who is invited to experience this pastoral scene? And who might be excluded, based on socio-economic standing? Curator: That tension between the idyllic scene and its potential exclusions is exactly what makes these seemingly straightforward landscapes so engaging. There's a narrative unfolding beyond just the picturesque composition. Are those groups picnicking and creating an idyllic scene of ease, or are we, as contemporary viewers, right to ask questions about whose land is represented in this scene, who labors unseen to make such leisure possible? Editor: And even further, who owns the resources depicted. Those little signifiers become powerful icons for conversations on labor and leisure, or accessibility to resources like clean water or beautiful nature scenes. They become potent symbols, both aspirational and potentially deceptive, as access to natural settings is a deeply classed issue. Curator: Well, I feel it has opened my mind to new meanings of the picture and new dialogues with nature through art. Thanks! Editor: I am glad we could use history as a conduit to current concerns. Thank you!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.