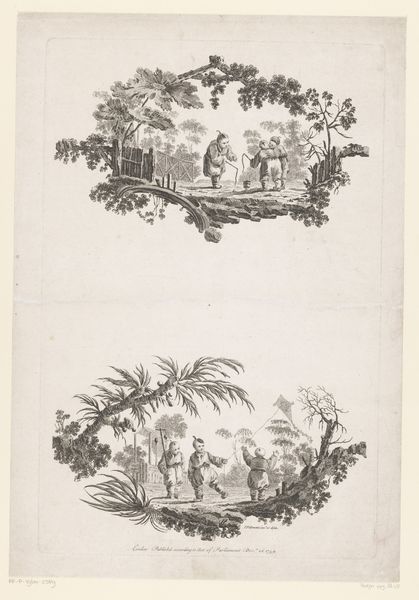

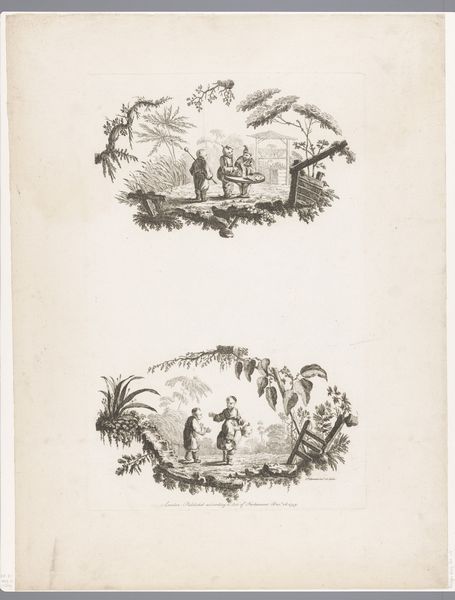

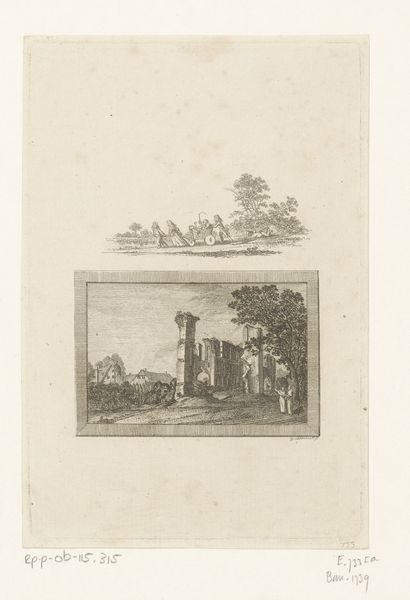

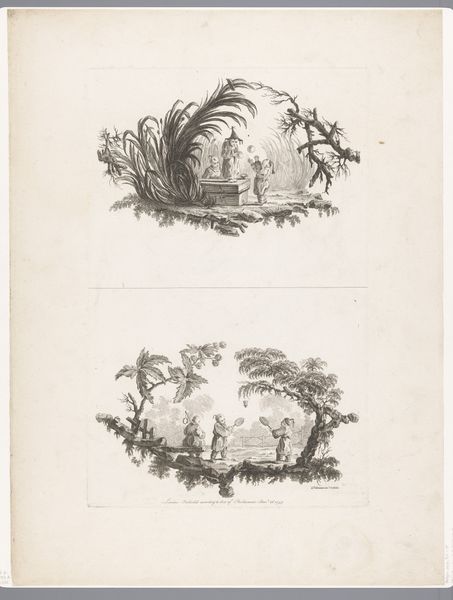

print, engraving

#

baroque

# print

#

old engraving style

#

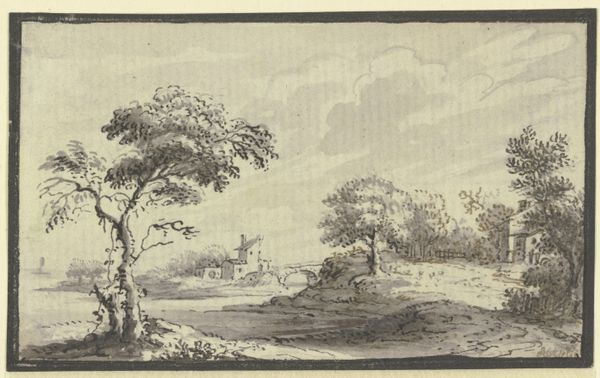

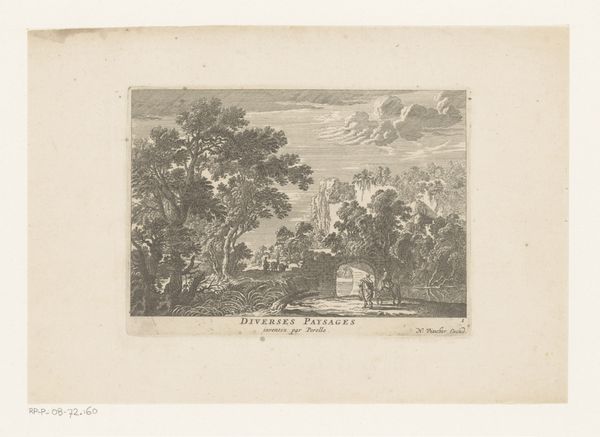

landscape

#

genre-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 421 mm, width 272 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have "Kinderen met bal en in wagen," or "Children with Ball and in Wagon," potentially from 1759 by Pierre Charles Canot. It’s an engraving currently held in the Rijksmuseum. The images appear almost like elaborate cartouches. I'm intrigued by how detailed yet whimsical they are. What strikes you most about the composition? Curator: Formally, observe the dual registers within this single print, each meticulously framed by ornate, curvilinear floral borders. Note how Canot employs a rigorous symmetry within each vignette, yet subtly disrupts this balance to maintain visual interest. For example, consider the placement of the children playing ball in the upper register, set against the background landscape, versus the family in the wagon. What contrasts can you identify? Editor: I notice the upper vignette has a more open composition, suggesting play and freedom, while the lower one, with the wagon and attendant, feels more contained and perhaps regulated. Curator: Precisely. The artist plays with spatial dynamics. Consider, too, the line work: how does Canot achieve tonal variation and a sense of depth using only line? Does this technique contribute to a particular feeling in each section? Editor: It’s fascinating! In the upper section, the lighter, finer lines suggest a sunnier, more open space. The darker, more dense lines in the lower section definitely emphasize the weight of the wagon and perhaps the implied social hierarchy. Curator: An astute observation. The strategic application of line and form within these self-contained visual fields constructs not just images but narratives about leisure and societal structures. Each element reinforces a deeper understanding of form and meaning, achieved solely through visual components. Editor: It’s remarkable how much information and feeling can be conveyed through something as seemingly simple as line work and composition. Thanks! Curator: Indeed. It prompts us to look closely at not only *what* is depicted, but *how* it is depicted.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.