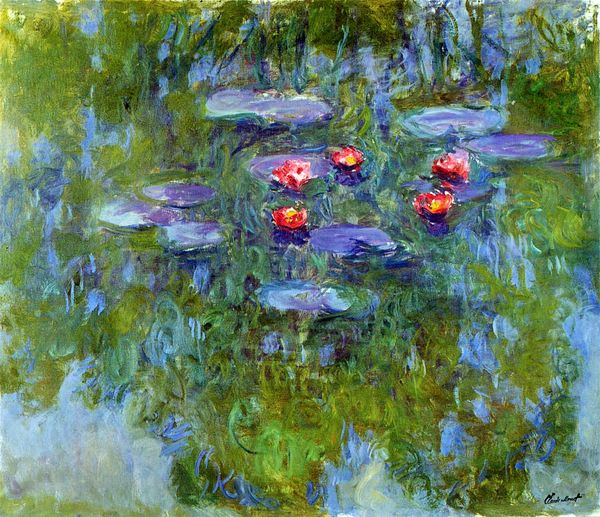

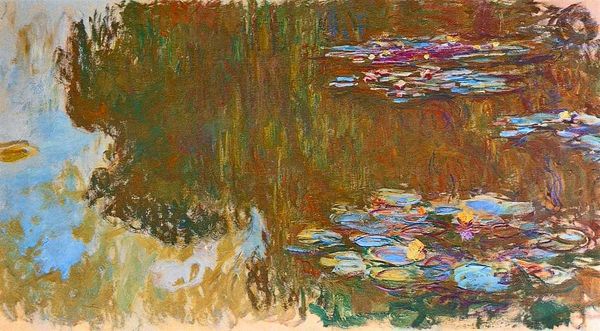

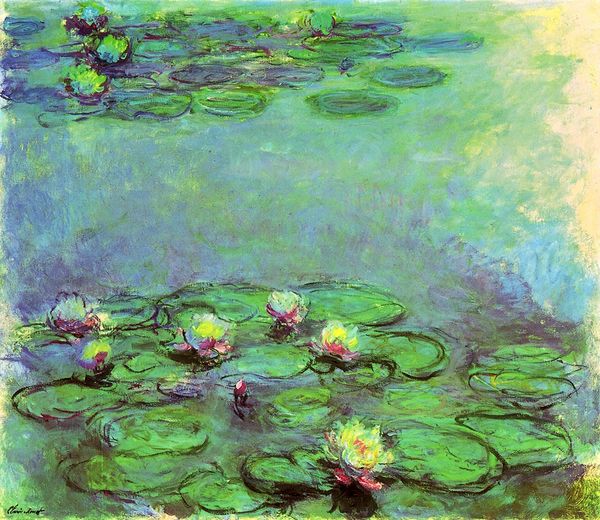

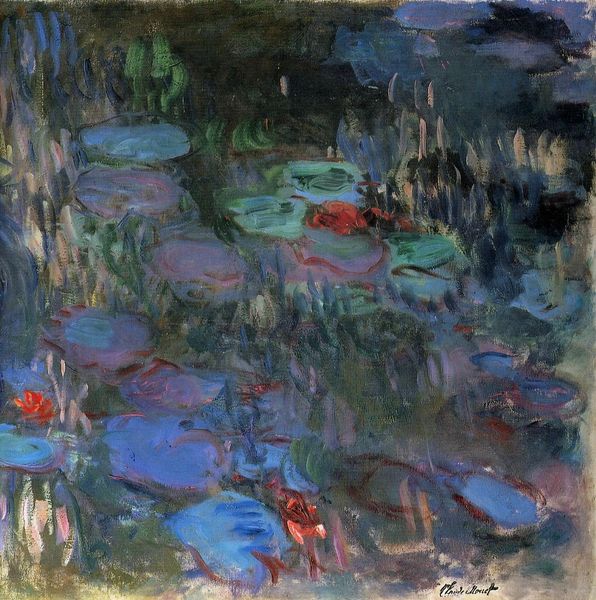

Copyright: Public domain

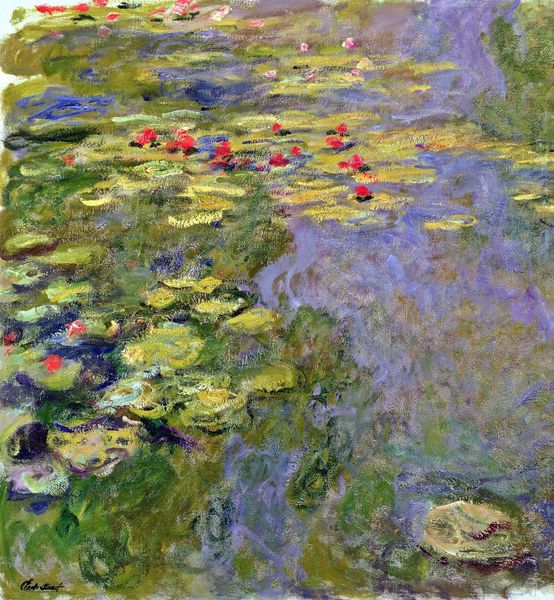

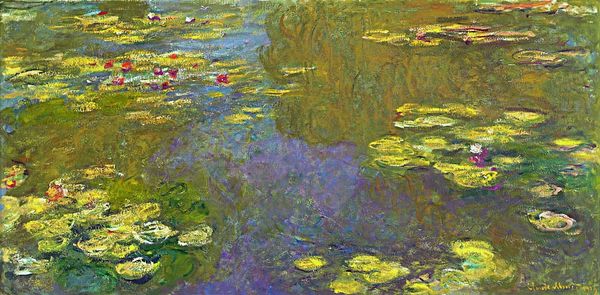

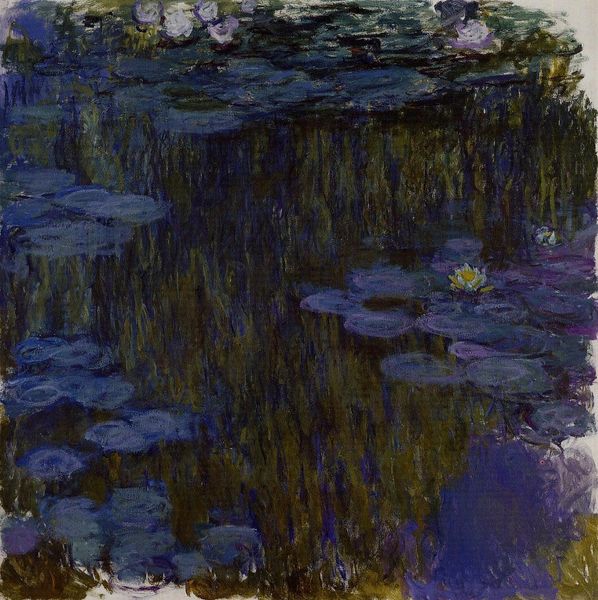

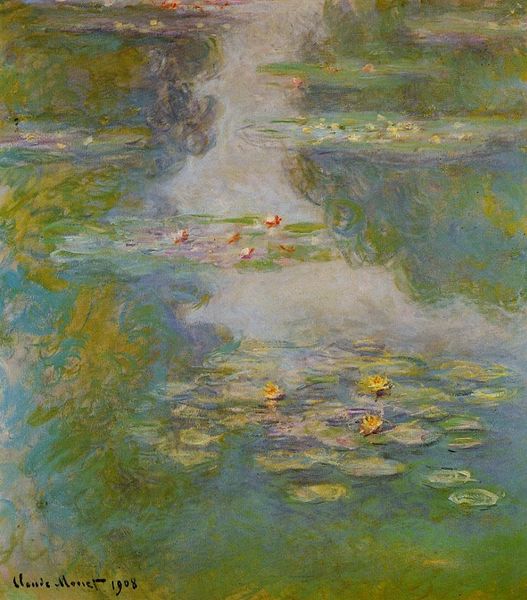

Editor: This is Claude Monet's "Water Lilies," painted around 1917. The canvas shimmers with soft colors, mostly greens and blues. What do you see in this piece, beyond just a pretty pond? Curator: Beyond the idyllic surface, consider the symbolic weight of the water lily itself. In many cultures, the water lily represents rebirth, resurrection, and enlightenment because of its ability to emerge from muddy waters into a beautiful bloom. Think about what that might mean for Monet at this later stage in his life. Editor: That's a great point. He painted these later in life when he was losing his vision. Is there a connection between his impaired vision and how he used symbolic associations? Curator: Precisely. The blurring of form, the dissolving of edges, could be interpreted as not just a symptom of his declining eyesight, but as a deliberate choice. A choice reflecting the transition to a different plane of seeing, a more spiritual, perhaps more essential form of perception, memory made visual. Does it bring to mind any stories? Editor: I hadn't considered it that way. Knowing his sight was failing, the lilies become more poignant, a reminder of beauty, resilience, the hope inherent in the natural world he devoted himself to observing. Curator: Indeed. His vision transforms into something more universal. And maybe that is the most profound lesson of cultural memory: things that once made you who you are eventually can represent something deeper and larger, if you give it a voice, in this case, through brushstrokes and color. Editor: This makes me rethink the power of his images and the story of his personal resilience. Thank you.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.