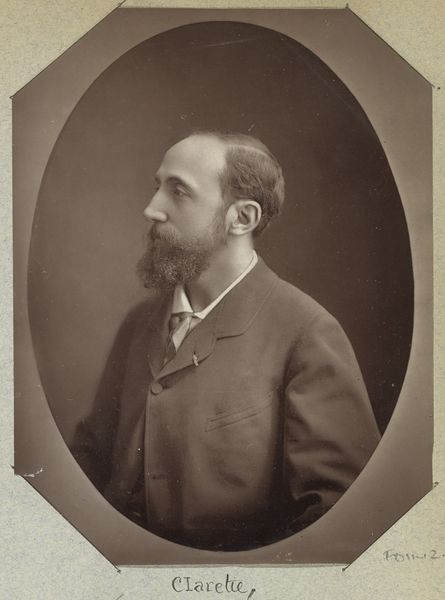

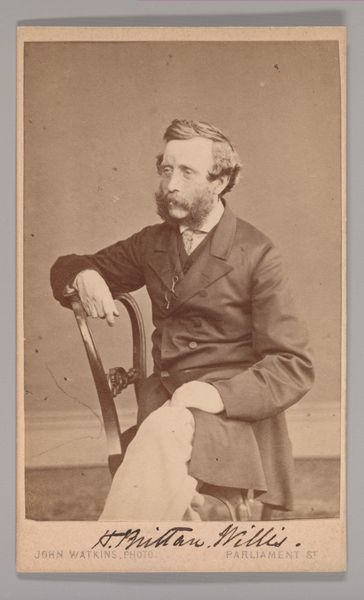

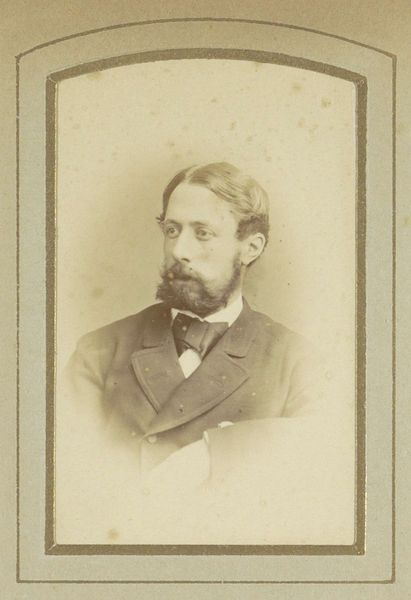

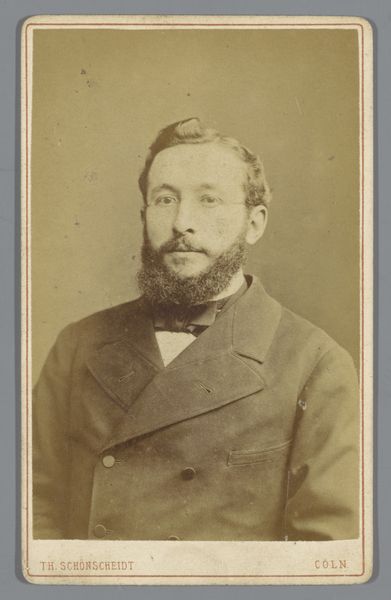

![[Philip Hermogenes Calderon] by John and Charles Watkins](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fd2w8kbdekdi1gv.cloudfront.net%2FeyJidWNrZXQiOiAiYXJ0ZXJhLWltYWdlcy1idWNrZXQiLCAia2V5IjogImFydHdvcmtzL2RjOGQ5YjAxLTU1ODYtNDcwZC04ZTZmLWYzYzZlMjQ5ZDlkMy9kYzhkOWIwMS01NTg2LTQ3MGQtOGU2Zi1mM2M2ZTI0OWQ5ZDNfZnVsbC5qcGciLCAiZWRpdHMiOiB7InJlc2l6ZSI6IHsid2lkdGgiOiAxOTIwLCAiaGVpZ2h0IjogMTkyMCwgImZpdCI6ICJpbnNpZGUifX19&w=3840&q=75)

Dimensions: Approx. 10.2 x 6.3 cm (4 x 2 1/2 in.)

Copyright: Public Domain

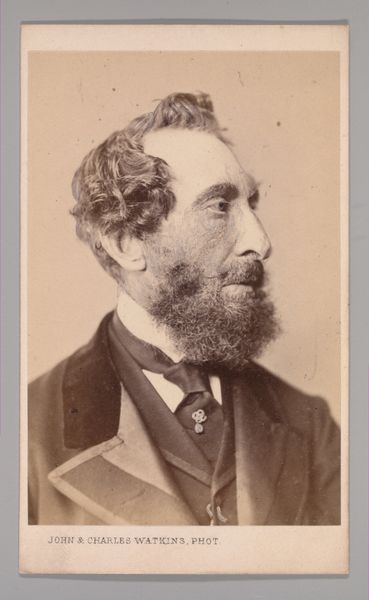

Curator: Before us is an albumen print from the 1860s, a portrait of Philip Hermogenes Calderon by John and Charles Watkins. It resides here at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Editor: He has a stern yet kind look on his face, doesn't he? I get a sense of seriousness and maybe even quiet resolve from this photograph. The sepia tones lend it such a timeless feel, a quiet gravity that you wouldn't get with modern photography. Curator: Exactly. These photographic portraits were instrumental in crafting and disseminating a very specific image of the Victorian artist, usually playing on the dichotomy between genius and social class, making him accessible and somewhat removed at once. Calderon himself was well known as a painter, associated with a group exploring historical and genre subjects. Editor: I think you can definitely read elements of Romanticism into his carefully cultivated appearance. I mean, look at the slightly untamed beard and hair— it suggests a man immersed in thought, perhaps at odds with rigid societal expectations. Was that the Victorian equivalent of the tortured artist look? Curator: Absolutely, these photographs often promoted a certain kind of masculine intellectualism. Consider the photographers, the Watkins brothers, catering to the Victorian market that craved images of noteworthy individuals, ensuring the artists were known by their public image, in addition to their artwork. This also allowed them some amount of artistic license with the poses. Editor: And you can see the effort involved, in making him relatable, like he is an accessible artist who anyone can befriend. Yet, his posture with crossed arms projects an intellectual, sophisticated persona which is somewhat detached from the world. Curator: Right. Also, the materiality itself plays a part. The albumen print gave the photographs a soft focus and range of warm tones, often enhanced to hide flaws. Each print also came in carte-de-visite size, ensuring the artist and artwork could literally travel anywhere. It’s a perfect mix of romantic ideals, photographic realism, and print reproducibility. Editor: Thinking about it now, it strikes me as fascinating how they utilized these portraits as tools to not only preserve images of artists, but to fashion the myth of the artist, creating an intriguing figure and selling that persona along with his pieces. Curator: These portraits offered access into elite circles, offering insight into Victorian cultural values that still resonate today, even if filtered through generations of artists whose legacies they have invariably influenced. Editor: Well said, thinking about photography today makes you think about image consumption, what we are shown, and by whom. I am glad we spent time observing how people managed their images, and what can happen when art becomes a commodity.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.