daguerreotype, photography

#

portrait

#

daguerreotype

#

photography

#

romanticism

#

mixed media

Dimensions: height 80 mm, width 70 mm, height 94 mm, width 81 mm, depth 17 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

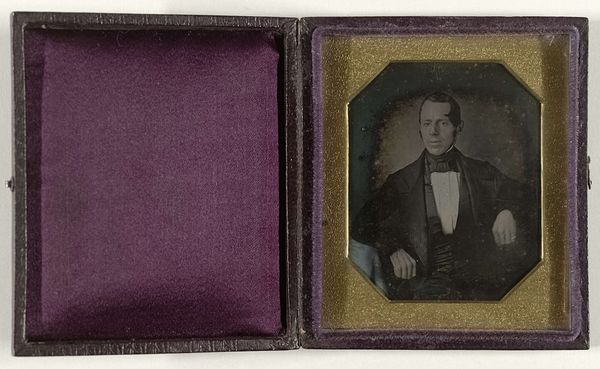

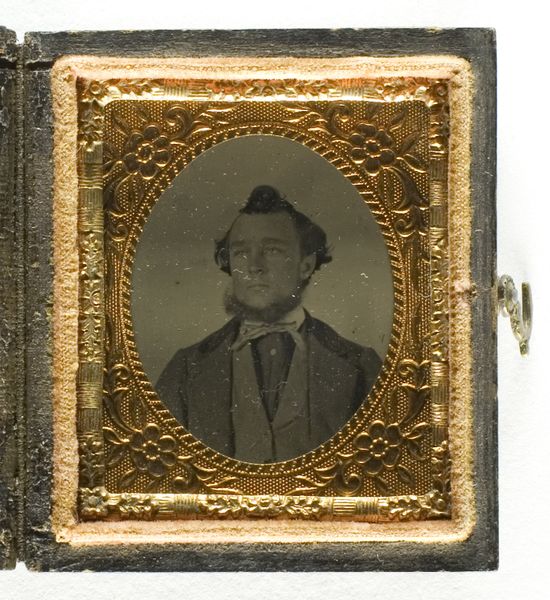

Curator: We are looking at a daguerreotype portrait, a photograph produced on a silver-covered copper plate. It’s titled "Portret van Johannes Hubertus Cornelius Lisman" and it's thought to be from around 1848. Editor: There's a ghostly feel about it, isn't there? It’s so small, encased like a precious jewel. The young man stares out with a sort of quiet defiance. Melancholy, maybe? Curator: Yes, the encasement adds to the preciousness, but it was also necessary to protect the fragile image. As for symbols, you'll note he's resting his arm on the back of the chair. It projects relaxation, though the rest of his posture is more restrained, almost formal. The pattern on his trousers gives it a twist of something unexpected. Editor: Good point! The checkered pattern jars slightly against the formality of the pose. Perhaps it’s a touch of youthful rebellion, a hint of playfulness that refuses to be completely suppressed by the societal expectations bearing down on him. Curator: Exactly! Also the frilly neckpiece – that's quite a detail. But beyond fashion, the pose is very consciously Romantic. Think of all those paintings of Byronic heroes gazing dramatically into the distance! Except here, the hero is looking straight at us. Editor: I read it as a vulnerability—a directness that cuts through the idealised Romantic figure. And think about the technology—this image captured with such painstaking method, represents truth—indexical truth – and stands as irrefutable fact that can still reach across centuries. Curator: It’s also about memory, isn’t it? The Victorians were obsessed with memento mori, and these portraits were often kept to remember loved ones after they’d passed. Holding onto what time steals away. Editor: Precisely, to freeze a moment. We are all familiar with having the power to endlessly reproduce images of ourselves, but he was aware that this may be his only real, reproducible image for life, for memory, to last potentially centuries... and here it is. That act gives this picture so much weight. Curator: True. To have sat still for what must have been an eternity. There's a weight there, a significance that's easily missed now. Editor: Looking at him, I almost feel a responsibility, now, not to forget his carefully preserved moment. And maybe that's the enduring power of portraits like these, especially ones caught so early on.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.