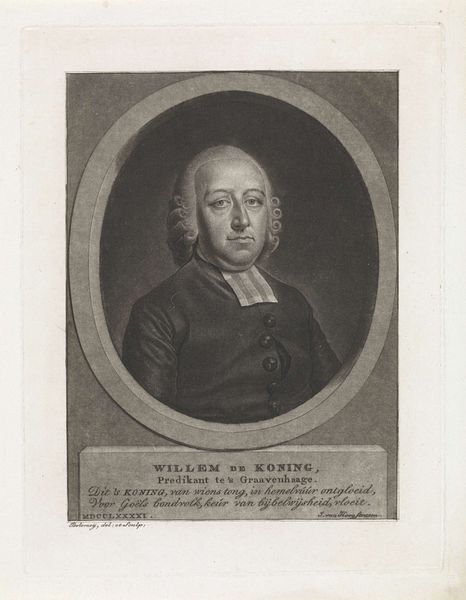

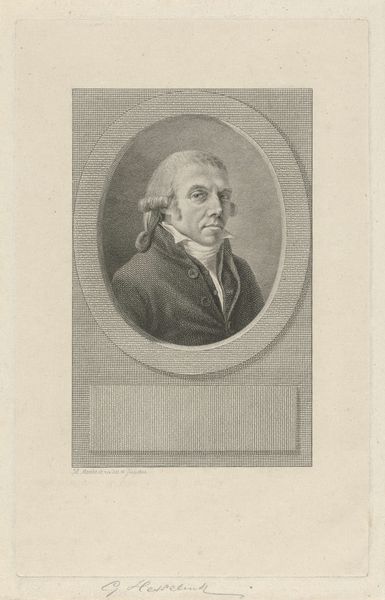

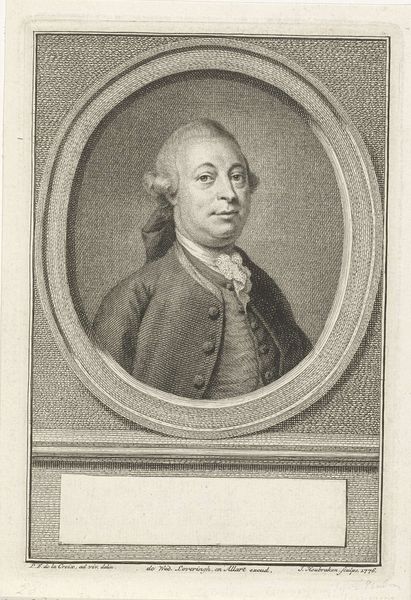

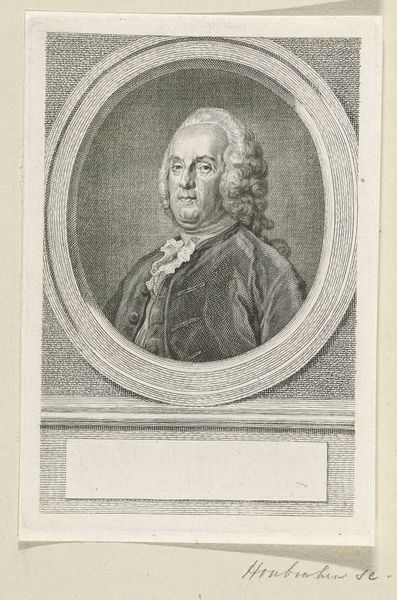

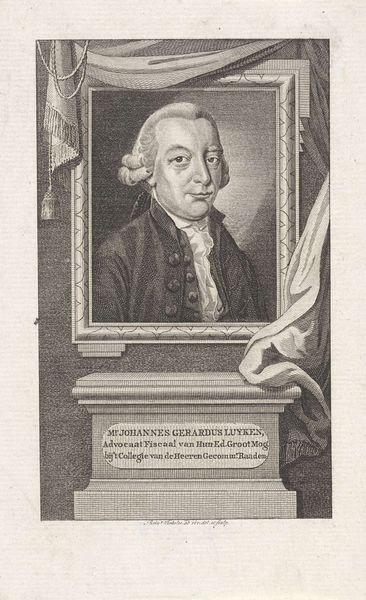

etching, engraving

#

portrait

#

pencil drawn

#

neoclacissism

#

light pencil work

#

shading to add clarity

#

etching

#

pencil sketch

#

old engraving style

#

personal sketchbook

#

pencil drawing

#

limited contrast and shading

#

sketchbook drawing

#

pencil work

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 94 mm, width 75 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This is Gerrit Konsé's "Portrait of Albert van Ryssel," an etching created in 1789. Editor: There's an almost haunting stillness to it, don't you think? The limited shading gives it a sketched, unfinished feel. Curator: Indeed. The piece reflects the prevailing Neoclassical style, a return to simplicity and order in the late 18th century. Look at the controlled lines, the focus on form rather than expressive emotion. This was, in many ways, a reaction against the extravagance of the Rococo period. Editor: The etching, in its monochrome nature, feels deeply rooted in a specific social strata, doesn't it? The subject is undoubtedly a man of means, whose status is amplified through representation in art. Curator: Absolutely. Portraiture at this time was largely the domain of the wealthy, reflecting power structures and the social elite's desire for representation and legacy. Note how the sharp details showcase the sitter's prominent, yet placid, features. Editor: But who was Albert van Ryssel, and what narratives are being intentionally—or unintentionally—omitted? We should be attentive to the unspoken social hierarchies implicit in art patronage of this period. What message was Konsé conveying by portraying him? What was the function and who was this artwork for? Curator: The engraving allows the image to circulate widely; it has a reproductive quality that paintings would not. The creation and dissemination of this portrait itself is a marker of social position for van Ryssel, as a lasting imprint within a visual culture dominated by, and designed to reinforce, established power structures. Editor: I agree, it also allows a study of both artist and sitter from a contemporary context. To explore the power dynamics at play here helps reveal who has been historically privileged by the gaze of art and the cultural significance attributed to portraiture. Curator: Thank you for those additional insights. It does make you see more than just an image on a page. Editor: Art invites us to engage critically, prompting reflections on historical contexts and how the values of the past might linger with us now.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.