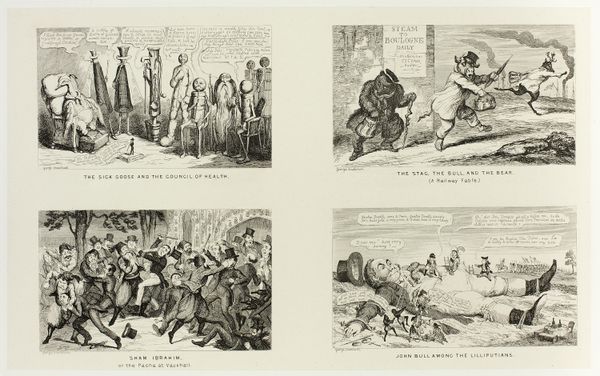

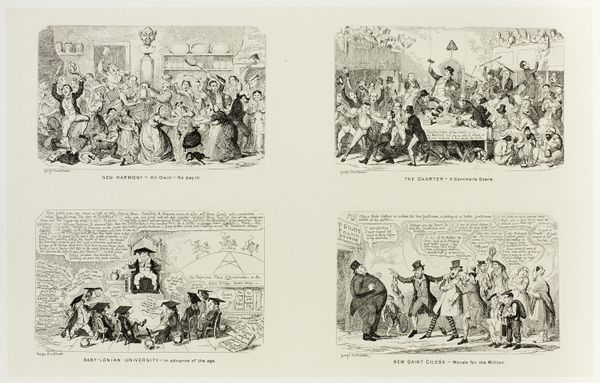

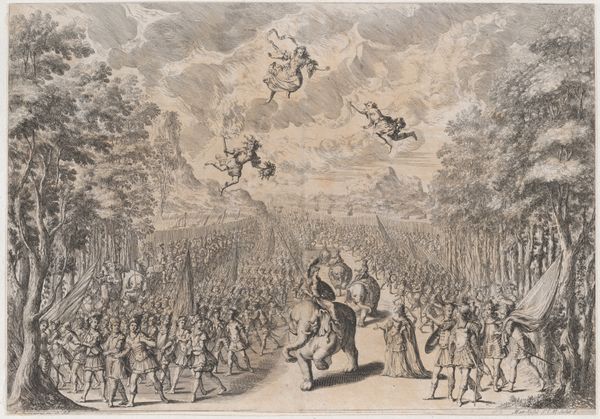

The Peace Society, or a New "Field of Action" for the Military - in "The Good Time Coming" from George Cruikshank's Steel Etchings to The Comic Almanacks: 1835-1853 (top) c. 1852 - 1880

0:00

0:00

Dimensions: 200 × 163 mm (primary support); 344 × 252 mm (secondary support)

Copyright: Public Domain

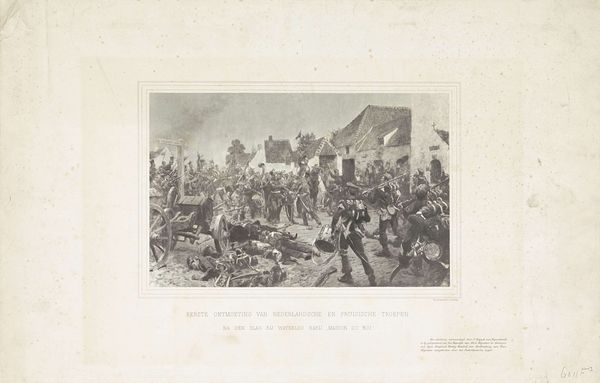

Curator: At first glance, this engraving presents an interesting juxtaposition of scenes, almost like a comic strip. The overall tone is quite chaotic and lively. Editor: Indeed. What we have here is "The Peace Society, or a New 'Field of Action' for the Military - in 'The Good Time Coming'" by George Cruikshank, dating roughly from 1852 to 1880. Cruikshank was a prolific British caricaturist. This piece uses steel etching, engraving, and drawing on paper. The print is now housed at The Art Institute of Chicago. You really get a sense for how materials like the etched lines create an accessible and cheap media of cultural transmission. Curator: Absolutely. Structurally, there’s a clear division between the two panels. The top scene depicts soldiers engaged in agricultural activities – harvesting wheat, tending to livestock, but even the livestock appear somewhat combative! It presents an image of repurposed military activity in a peaceful context, ripe with satirical intent. And lower section shows something different... Editor: Below, we observe a procession led by a conductor figure, seemingly celebrating "new politics and polkas," as the text beneath suggests. It's almost carnival-like. The banner reads, "Liberté, Egalité, Fraternité, Fiddle-de-dee." The juxtaposition feels incredibly significant, considering Cruikshank's era. Are these political and social structures being questioned or promoted? How do you see the production values of print aligning to accessibility for specific Victorian demographics? Curator: Well, given the social context of Victorian England and its class-based structures, there's definitely an element of social critique here. Cruikshank’s caricature style was very popular among the growing middle class, which was concerned with social reforms. By equating the military's activities to something almost comical— like the conductor figure who appears buffoonish—the print likely aimed to satirize the elite while subtly promoting an image of useful labor to the lower orders of society. The materials used, being inexpensive, speak to an effort toward broad social penetration. Editor: That’s fascinating. Looking at the details— the contrast in textures, the densely packed figures versus open space, and especially the implied narrative through the panelled layout—it’s clear he wasn’t simply making an anti-war statement. It could be seen more broadly to say something new was coming from political theater to repurposed militaries and work for new industries. Curator: Precisely. We are witnessing art acting as a tool for negotiation and social commentary in a society grappling with progress, consumerism, and military restructuring. Editor: The layering and structural division emphasizes his political and artistic commentary— a commentary deeply rooted in the changing values and anxieties of his time, accessible to wider demographics through inexpensive means. Curator: Yes, considering production processes allows to examine broader changes to both production as well as political power structures of England's Victorian period. Editor: Definitely. This has opened my eyes to think more deeply about artistic purpose and means for transmission!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.