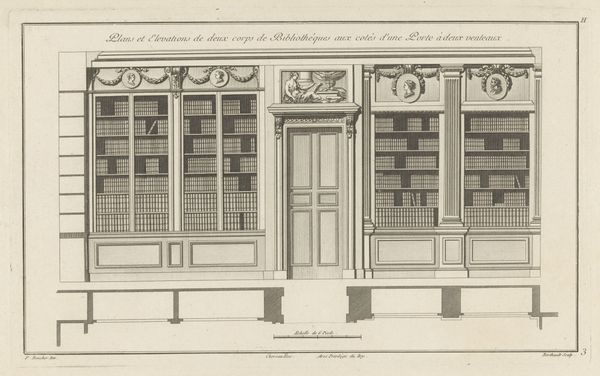

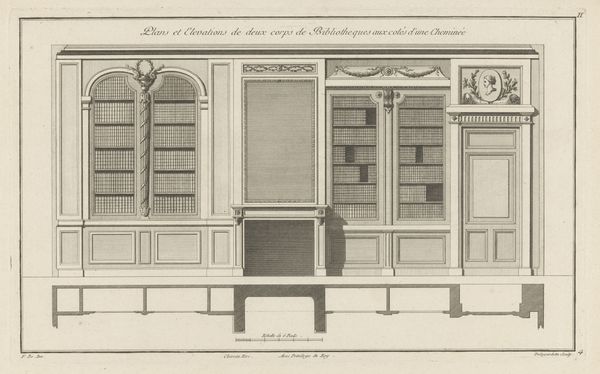

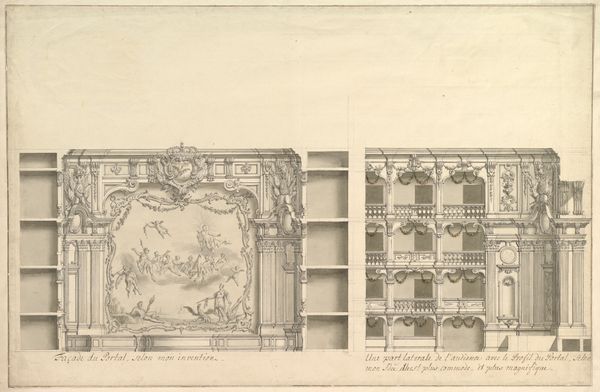

Dimensions: height 228 mm, width 364 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

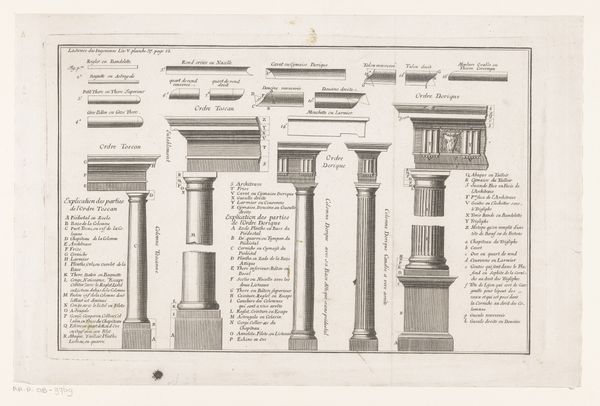

Curator: At first glance, there’s something deeply calming about the symmetry of this composition. Editor: Calm maybe, but also strangely sterile. Like an architect's idealized vision, rather than a lived-in space. We're looking at "Bibliotheek," or "Library," an engraving dating back to 1767 by Jean François de Neufforge. Currently held in the Rijksmuseum’s collection, it offers a detailed view of a grand bookcase design. Curator: The choice of print as the medium is very interesting. It really puts this in dialogue with broader accessibility, despite depicting something grand. This image isn’t just about displaying wealth, it’s about the social statement of knowledge and taste-making. A print like this circulates ideas about how a library *should* look and function within aristocratic circles. Editor: Agreed. Look at the precision of the lines, the clear delineation of each volume. The materials speak of controlled production, almost mass production for a certain class of patron with the financial means to replicate such grandeur. The paper stock, the ink—all commodities that reflect the economics of artistic creation and consumption during that era. And, while it mimics the effect, stone carving in particular took many specialized hands to complete! Curator: Absolutely. Consider the context. The Baroque style, with its emphasis on ornamentation, functioned to impress. But this isn't solely about decoration; it's a projection of power linked directly to intellectual authority. Each volume displayed implies knowledge mastered, creating a visual argument for social dominance. And this image allows them to imagine *having* the real thing. Editor: And also, let’s not forget, these engravings would be crucial for artisans, cabinet makers to physically build something like this. Each line, each shadow suggests the specific techniques and labor processes involved in high-end interior design, reflecting a hierarchy of craft that ultimately dictates what “high art” means. I imagine the cost for the construction being extremely high at the time, limiting the possibility of even replicating such image in real life. Curator: Indeed, the layered meanings here are rich. I initially read it as a celebration, now I find its rigid structure reveals underlying codes about power structures within 18th-century society. Editor: Exactly, beyond its surface, the piece encourages deeper inquiries into consumption, craftsmanship, and status through materiality.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.