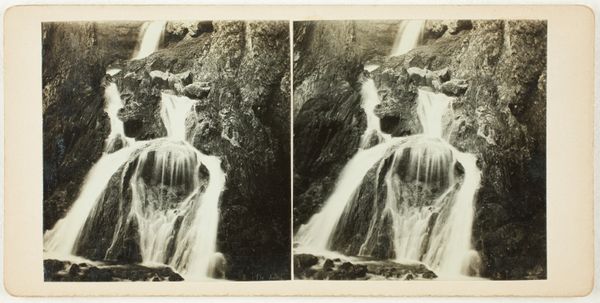

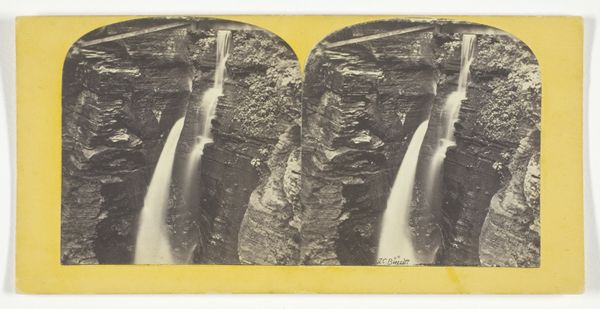

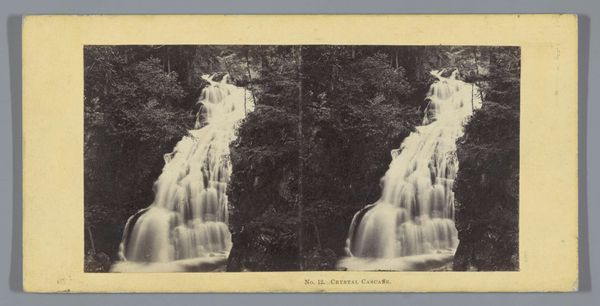

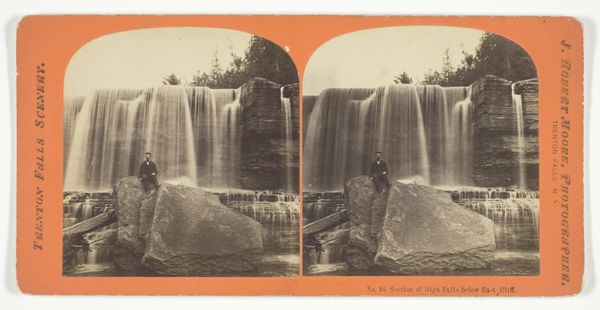

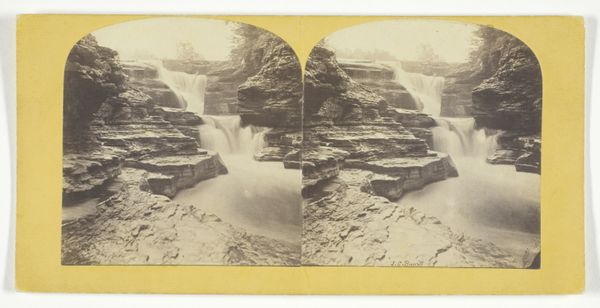

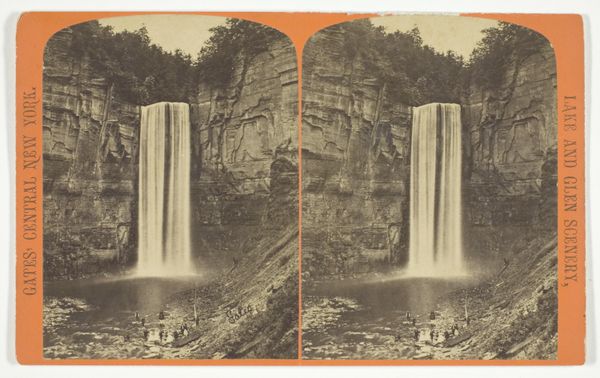

Dimensions: 9.4 × 7.7 cm (each image); 10 × 17.8 cm (card)

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: This is William Henry Jackson’s "Cheyenne Falls," a gelatin silver print from between 1879 and 1892. It's… well, it's quite stunning in its starkness. The composition is dominated by the rock face and the cascade itself. What do you see in this piece? Curator: I see more than just a pretty picture. Look at the gelatin silver print itself. Photography in the late 19th century was transforming how the American West was perceived, but this wasn't some neutral recording. Jackson's images were commodities. Editor: Commodities? Curator: Absolutely. Consider the materials – silver, gelatin, paper – all components of a burgeoning industry. The image of the untamed West, neatly packaged and sold as a stereograph, fueled westward expansion, influencing tourism, settlement, and resource extraction. Editor: So, the 'truth' of the photograph is tied to… consumption? Curator: Exactly. Jackson wasn’t simply documenting; he was producing a consumable image of the West. The Hudson River School-esque romanticism combined with photographic realism becomes a powerful tool for shaping public perception. Notice how he frames the waterfall, almost making it look... manageable. Editor: So, instead of thinking about this as art capturing nature, we should consider the industrial processes behind it and the societal forces at play? Curator: Precisely! It forces us to reckon with how images, objects, shape and often distort, our relationship with both art and nature. Editor: That’s a fascinating, and somewhat unsettling, perspective. It makes me reconsider the power dynamics inherent in even seemingly straightforward landscape photography. Thanks for expanding my view. Curator: My pleasure. Thinking materially is key.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.