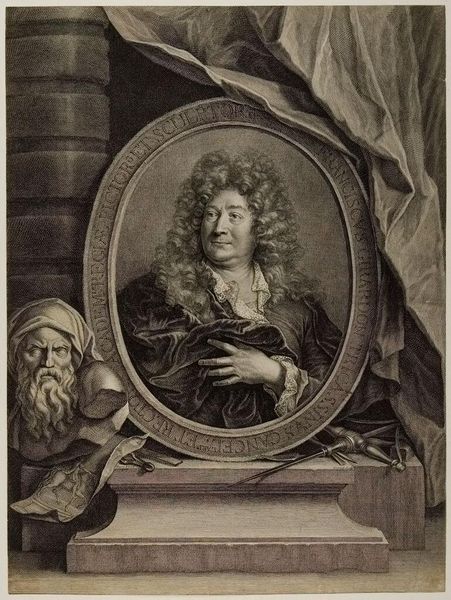

Portrait of Carel Quina (1622-89), Knight of the Holy Sepulchre and Amsterdam-born explorer of Asia 1669

0:00

0:00

painting, oil-paint

#

portrait

#

baroque

#

painting

#

oil-paint

#

figuration

#

underpainting

#

costume

#

genre-painting

#

academic-art

Dimensions: height 40 cm, width 31 cm, thickness 0.8 cm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have Jacob Toorenvliet's "Portrait of Carel Quina (1622-89), Knight of the Holy Sepulchre and Amsterdam-born explorer of Asia," created in 1669. The medium is oil on canvas, and it exemplifies portraiture from the Dutch Golden Age. Editor: It strikes me as rather melancholic. Despite the apparent wealth indicated by his clothing and surroundings, there's a certain world-weariness in his gaze, and in the dim, muted palette. The map spread before him, presumably charting his explorations, feels heavy, laden with unspoken stories. Curator: Indeed. It is important to situate such works within the context of Dutch mercantile expansion and colonialism. Quina was a significant figure in the Dutch East India Company, a venture which we know caused immense violence and displacement for many Asian populations. The map here speaks not just to exploration, but also domination. Editor: Absolutely. And how fascinating is the presence of the young dark-skinned boy in the left-hand corner? His presence feels like a ghost, a shadow that follows Quina, a reminder of the human cost inherent in his adventurous endeavors, but also potentially of servitude. Curator: Portraits of this era are always so calculated. Everything is meant to signal status, virtue, and power. Consider his pose, holding dividers as a symbolic gesture to measuring the world—and also as claiming it. Note too his attire, including the symbolic insignia associated with the Knight of the Holy Sepulchre. Editor: While simultaneously subtly acknowledging the inherent violence interwoven with trade, exploration, and self-aggrandizement in the 17th Century? Or is this an idealized and sanitized version meant for a Western European gaze? Does it invite critique, or does it deflect? It feels so complex. Curator: What do you mean? Such images operated as clear status markers within specific social circles. Editor: I just wonder whose story truly is at the forefront. We view Carel Quina but through whose gaze? In his role of an activist, is he merely performative and/or does he recognize the role his image played within society. The gaze that locks me, even now, within its narrative! Curator: Reflecting on Toorenvliet’s portrayal and considering what was purposefully framed. We see how Dutch society crafted an image to project the values of status and worldly claim, Editor: An artistic encapsulation of the era’s paradoxical complexities, laid out upon an exploitative world. The work's capacity to stimulate these discourses reveals a lingering challenge in art to recognize our shared, multifaceted humanity in an exploitative and dominating system.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.