drawing, etching

#

drawing

#

animal

#

dutch-golden-age

#

etching

#

landscape

#

horse

#

genre-painting

Dimensions: height 132 mm, width 158 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

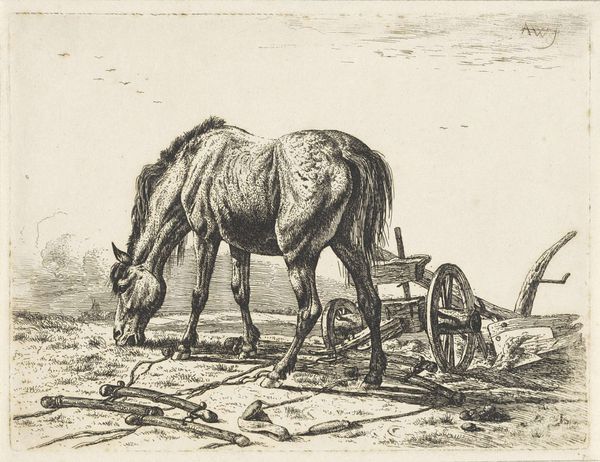

Curator: Look at this etching, a print really, made by Simon de Vlieger sometime between 1610 and 1653. It's titled "Rustend werkpaard" - "Resting Workhorse." Editor: That horse looks beat, utterly knackered, you know? Its head's hung low like it's trying to find wisdom in the dirt. Makes you feel for the poor creature. Curator: The Golden Age of Dutch painting saw an explosion of genre scenes. The relationship between humans and animals, particularly working animals like this horse, became a focal point, mirroring larger conversations about labor, rural life, and the social hierarchy of the time. The workhorse represents a critical labor force, especially with the prominence of trade during the period. Editor: Right, it's work. It feels like there's an honesty, a grittiness in de Vlieger's line work here that’s captivating. I find it amazing he created this out of ink, that is etching; it brings to my mind the daily slog, doesn’t it? A little barrel lays nearby, with a rope tethering the work horse down in his needed pause. Curator: I agree. By centering the workhorse in the frame, de Vlieger elevates the animal's importance. This artistic choice aligns with a broader social shift during the period. Acknowledging that laborers deserve respect and consideration for their labor even as larger Dutch painting focuses on genre painting and landscapes to symbolize status, value and privilege. Editor: Absolutely. It reminds me of the stories my grandfather used to tell me about farm life – the smell of hay, the heft of the harness, the bond between the farmer and his animals. The etching medium suits it, don’t you think? Its delicate detail really contrasts the powerful physique of the tired creature. Curator: Indeed. The artist has depicted a moment of respite that belies broader, unspoken issues of exploitation that intersect the human-animal relationship, in the specific sociohistorical contexts of burgeoning capitalism and global trade networks. It forces the contemporary viewer to look not just at this moment in isolation but in connection. Editor: Definitely leaves a deeper impression, right? Seeing this, one is prone to feel sympathetic. It’s those heavy flanks and weary posture, beautifully etched, makes one grateful to be an artist instead of a draught animal. Curator: I agree. Art always allows us an occasion for contemplation. Editor: To moments of respite, eh? Let's grab a coffee.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.