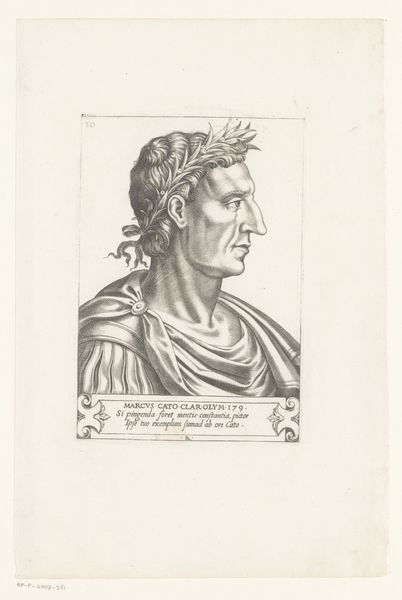

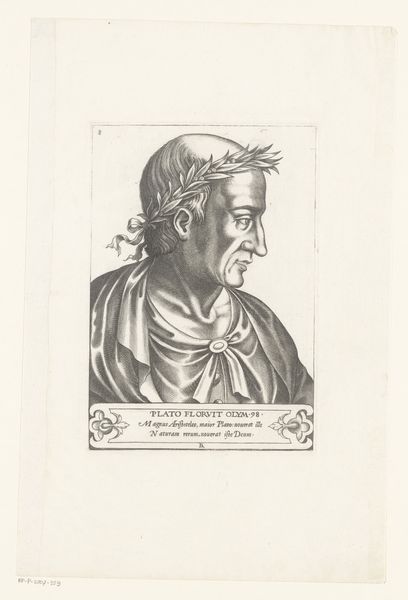

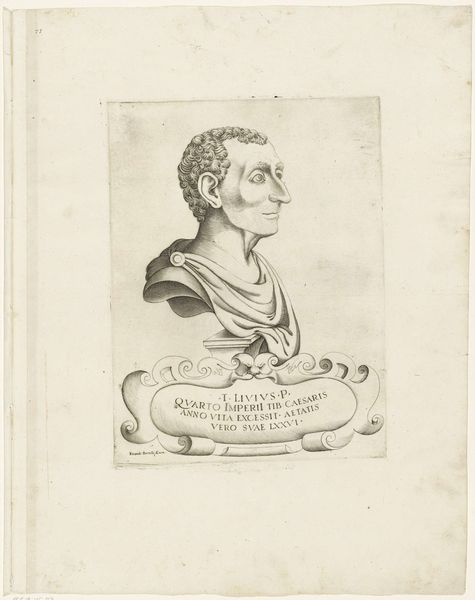

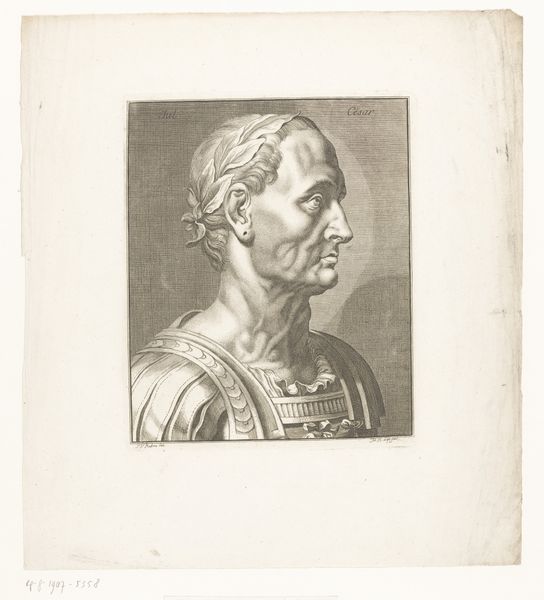

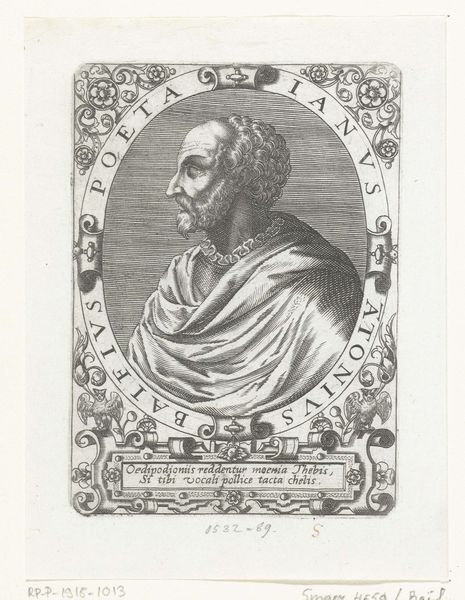

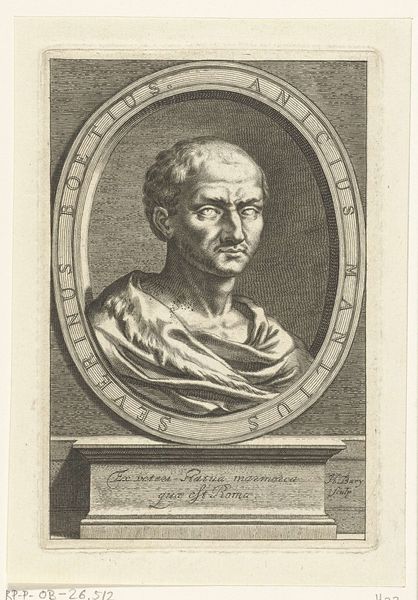

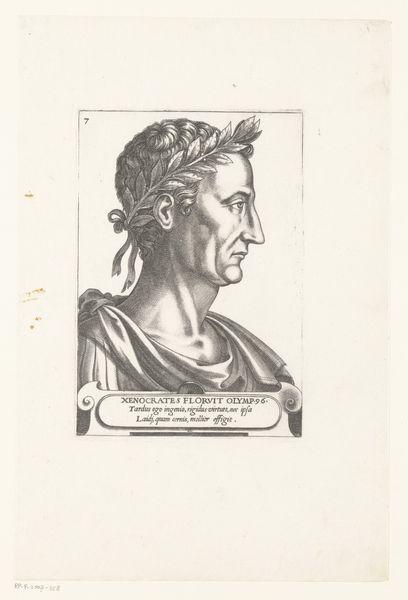

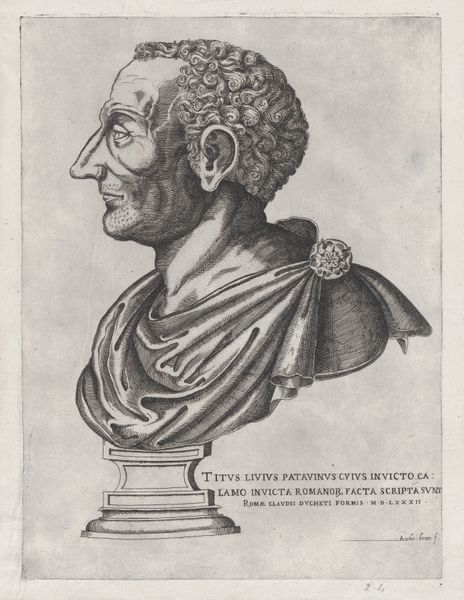

print, engraving

#

portrait

# print

#

11_renaissance

#

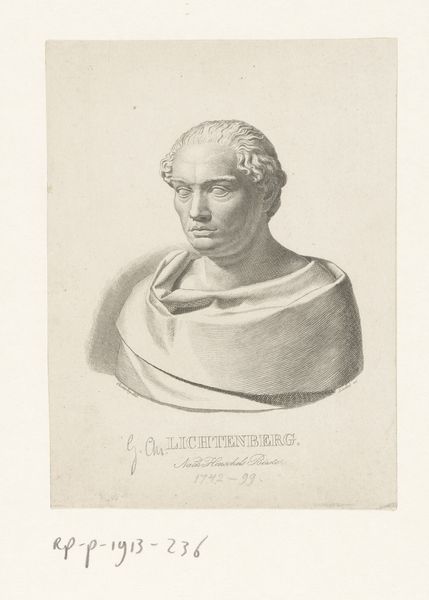

pencil drawing

#

portrait drawing

#

northern-renaissance

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 175 mm, width 121 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Tell me about this print. Editor: This is a portrait of Marcus Tullius Cicero, made in 1566 by René Boyvin. It’s an engraving. The lines are incredibly fine and detailed. What strikes me is the clear skill involved in its creation, so different from today's mass-produced images. What can you tell me about this engraving from a materialist perspective? Curator: Well, consider the labour involved. Every line you admire was etched painstakingly into a metal plate. This wasn't just about artistic vision; it was about skilled craftsmanship, a trade learned through years of apprenticeship. How do you think the act of engraving itself shapes the final image? Editor: I suppose the medium dictates a certain formality and precision. Unlike painting, where you can blend and layer, engraving demands a clear, deliberate mark. Do you think the choice of printmaking had social or economic implications? Curator: Absolutely. Prints democratized images. Unlike unique paintings reserved for the wealthy, engravings could be reproduced and distributed widely. This impacted how Cicero's image and ideas were disseminated throughout society. Whose patronage would be involved in the creation of this image and its subsequent distribution? How might this portrait have influenced perceptions of Cicero in the 16th century? Editor: It makes me realize that art production is also about labor and market access. Boyvin wasn't just expressing himself; he was participating in a complex system of patronage, production, and distribution that deeply impacted society. Curator: Precisely. And seeing the portrait this way allows us to view it not just as an object of aesthetic beauty, but as a artifact within the larger fabric of social and economic life of the era.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.