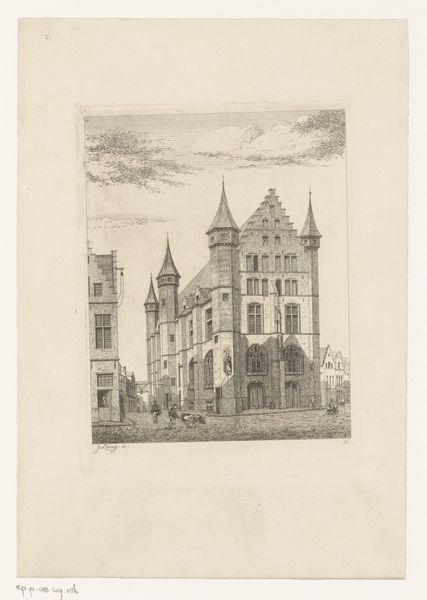

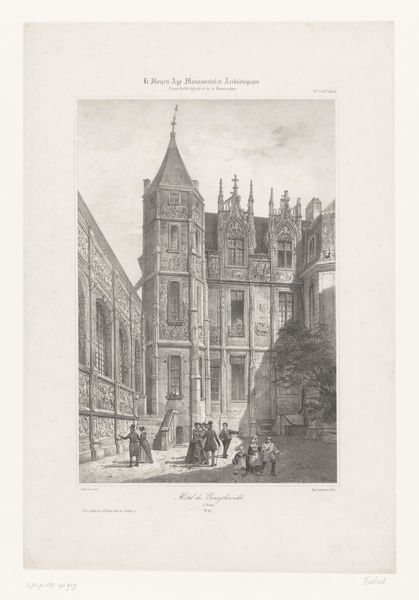

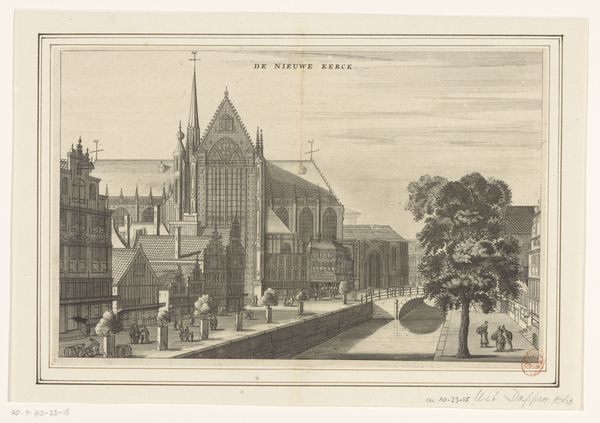

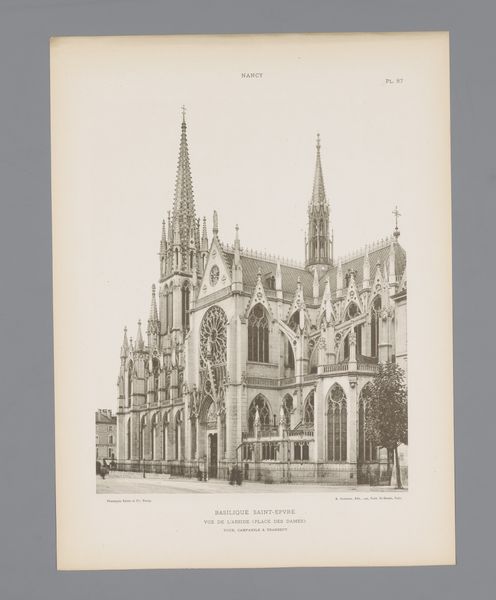

drawing, print, engraving, architecture

#

drawing

# print

#

pencil sketch

#

old engraving style

#

romanticism

#

cityscape

#

engraving

#

architecture

#

realism

Dimensions: height 172 mm, width 208 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This is Jean Théodore Joseph Linnig’s "Vleeshal," an engraving dating back to 1849. The delicate linework captures a building that seems both imposing and strangely serene. Editor: It's the textures that strike me immediately. Look at the meticulous cross-hatching suggesting the stone's weight and the light playing on its surface. What building materials would have been available and used? It speaks volumes about the economic conditions of the time. Curator: Indeed. Linnig wasn’t just representing a building; he was documenting the very fabric of urban life. "Vleeshal," which translates to Meat Hall, held a central function within its community. A civic structure whose existence suggests the rise of formalized market economies, especially as a center for what looks like a primary component in that economy - livestock. Editor: So the building material, readily available local stone no doubt, determined both its physical presence and, by extension, influenced the daily lives and interactions within the town. What's interesting is Linnig’s artistic license. Is it idealized or accurate? Does the light cast hide any specific marks or reflect positive community impressions to influence a modern audience, that sort of thing? Curator: It’s hard to say without a deeper archeological and archival context, although this could be a commissioned piece celebrating municipal architecture or trade, to attract merchants. Realism was developing but romantic ideals persisted in artistic tastes. Linnig's choices, and his patrons influence, were crucial in shaping this visual narrative. It speaks to the very power dynamics embedded in art production itself. Editor: You see the print then as participating in that creation of civic identity, emphasizing the prosperity presumably circulating inside. How would the people who worked at the Vleeshal respond, how does it aestheticize their labour, elevate a crucial building material to be more presentable than not? I wonder if Linnig romanticized the working conditions inside… Curator: Perhaps. The engraving invites questions not just about representation, but also about who is represented, who isn't and the values being subtly promoted within the artwork's reach and circulation as a visual artifact within a socio-economic fabric. Editor: So, more than a snapshot, it's a crafted statement. Food for thought, so to speak, about both artistic expression and social commentary through accessible visual media. Curator: Exactly, and with Linnig's beautiful craft, we see the interconnectedness of history, economy, art, and the making of visual cultures during a rapidly transforming society.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.