painting, oil-paint

#

baroque

#

painting

#

oil-paint

#

vanitas

#

realism

Dimensions: 52 cm (width) x 63.4 cm (height) (Netto)

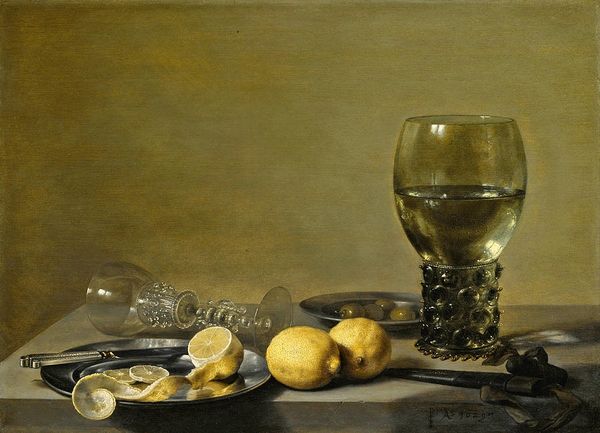

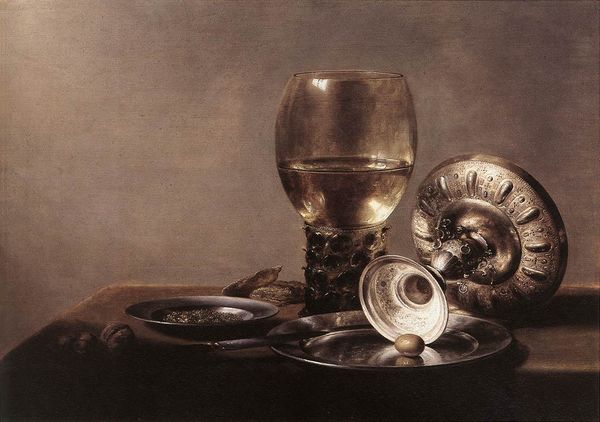

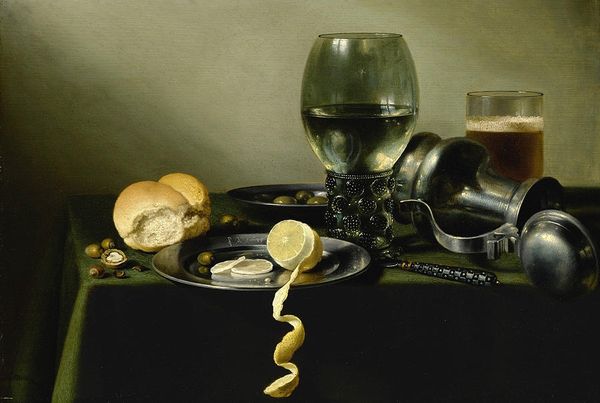

This still life was painted anonymously, using oil on canvas. Notice the way the light glints off the surfaces of the glass and metal vessels. This is where the painter really shows their stuff. Consider the labour involved in creating these objects. The glassblower, responsible for the delicate goblets, the metalworker who hammered the plates and bowls into shape. These processes involve intense heat, demanding physical skill, and a deep understanding of materials. The craftspeople were essential players in the economy of the time, producing the very stuff that paintings like this celebrate. The painter, too, was a kind of artisan. They had to grind pigments, stretch canvas, and mix their paints. Looking at the finished picture, it's easy to forget these processes. But paying attention to the making helps us understand the painting's value, both as an artwork and as a record of a world of labour.

Comments

statensmuseumforkunst about 2 years ago

⋮

The painting is on an oak panel to which a wood structure called a cradle has been added at a later stage. The cradle was made during a previous stage of conservation aimed at stabilising the wooden panel. Wooden panels cannot withstand changing climatic conditions. If the surroundings are too humid or too dry the wood can shrink or swell. A cradle could help prevent this. The method, which was common practice around 1900, consists of gluing battens of wood to the back of the painting in the direction of the grain, then inserting loose slats crosswise. Today the method is not considered ideal because the loose slats often get jammed, holding the panel in a rigid position with the risk of cracks when it moves. We now stabilise panel paintings using more careful and flexible methods.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.

statensmuseumforkunst about 2 years ago

⋮

A special type of still life is about the remains of meal. This theme became popular in the Dutch city of Haarlem, where the almost monochrome fashion of painting developed during the 1630s and 1640s. The protagonist artists are Pieter Claesz (c.1597/98-1660) and Willem Heda (1594-1680). An unknown artist from their immediate circle has painted Still life. Breakfast Piece in a Stone Niche. Someone has eaten what was on the pewter plate; only a bit of olive is left remaining on a plate of Chinese porcelain. On the move, the unfortunate guest has overturned a silver tazza, but two beautiful glasses, half-filled with wine, are left standing. The artist lets us think for a moment that the layout is part of our own reality, because the wall is cut off by the edge of the picture, and the pewter plate and the knife seems to topple out of the picture plane and extend into the viewers space. The deceptive realism is reinforced in the very way of using the brush - the artist imitates the surface structure of the various objects. That is, the lemon's shell is bulging and uneven, the underside of the silver tazza has the silversmith's processing imprinted as tangible surface structure. Both parts make the light in the existing room (i.e., now the museum’s exhibition hall) reflect and flicker in the same way as it would have done in real life. An important element in this and many other still lifes is that the artist wants to deceive his audience.