drawing, carving, print, woodcut

#

drawing

#

carving

#

pen drawing

# print

#

figuration

#

woodcut

#

northern-renaissance

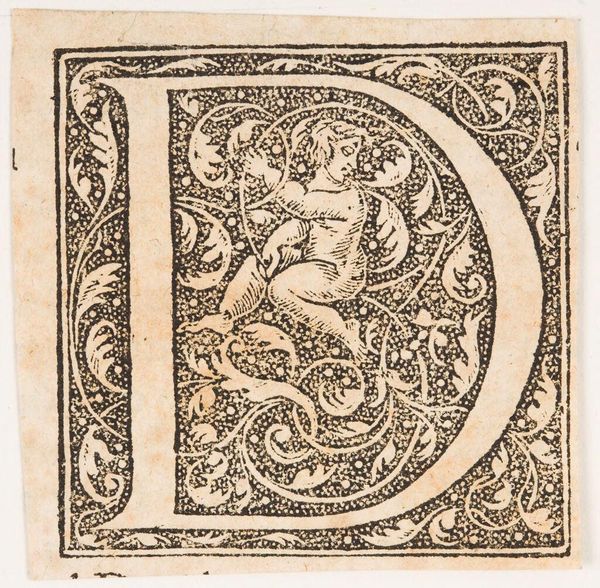

Dimensions: Sheet: 1 7/8 × 1 7/8 in. (4.7 × 4.8 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: This small woodcut, "Initial letter C with putto," was created by Heinrich Vogtherr the Elder between 1533 and 1540. It’s a wonderful example of Northern Renaissance printmaking currently held in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Editor: Immediately striking is its density. So much contained within such a tiny square. The black and white contrast creates a dramatic, almost overwhelming effect. Curator: Indeed. These initial letters were designed for print, often used to decorate the opening of a chapter in a book. Think about the skill and labor involved in carving such intricate detail into a block of wood, the precision needed for reproducible imagery, and the way literacy and book production were increasingly shaping the social landscape. Editor: I find myself focusing on the image itself, this chubby putto holding a scythe. What kind of cultural values did these types of figures signal? The artist is giving us classical imagery interpreted through a very Northern lens. Look at his face – less idealized beauty and more…character. Curator: Absolutely, and let’s consider how these images circulated. Prints were relatively inexpensive compared to paintings or sculptures, making them accessible to a broader segment of society. What impact did this accessibility have on the dissemination of humanist ideas and visual culture in general? Editor: A wide one, surely. But is the charm offensive of such cute propaganda blunted somewhat by what tools and messages it ultimately served, thinking of the Reformation brewing at that moment? Who could own it? Who *wanted* to own it? Curator: An astute point about ownership and influence. The production of these prints was closely tied to the economics of the printing industry and the patronage of wealthy merchants and civic leaders. The "Initial C" represents the intersection of artistic skill, economic forces, and the evolving role of images in early modern Europe. Editor: Seeing the detail is breathtaking when you realize that someone had to *carve* it all out of a block, but there is a flatness that makes me appreciate the technique and how it speaks to accessibility in this age of art production and consumption. Curator: Considering this letter “C” now, within the context of both printmaking’s processes and its political reverberations, makes it so much more fascinating to me! Editor: Indeed! An object’s journey and function often tell us more than what immediately meets the eye, doesn't it?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.