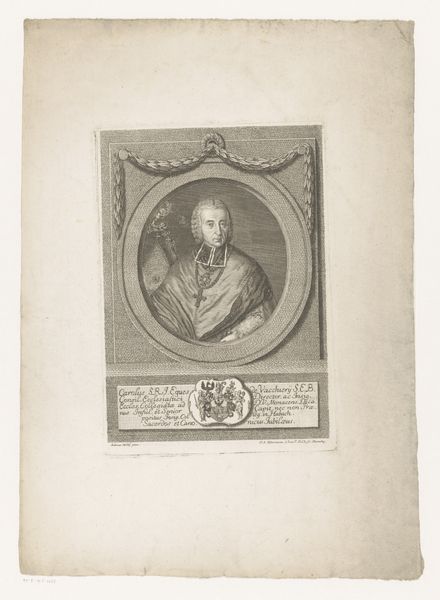

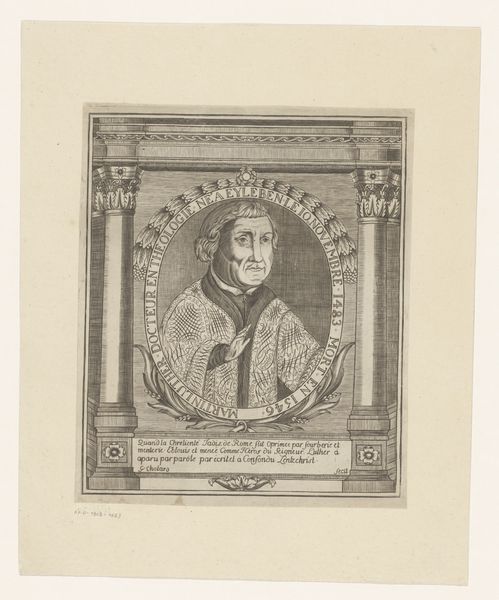

print, engraving

#

portrait

# print

#

classical-realism

#

11_renaissance

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 151 mm, width 106 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Looking at this engraving—a print from between 1755 and 1765 by Sèbastien Pinssio—of Gian Giacomo Trivulzio, I am immediately struck by its resolute composure. It is hard not to respect that direct gaze! Editor: I’m drawn in too, but in a different way. Look at the lines of that engraving; it speaks of craft. The precision needed to depict Trivulzio's face, each detail etched by hand… it highlights a skilled labor rarely visible in our contemporary context. The artistry is plain in how Pinssio used the printing press to achieve it. Curator: True. There’s such a strong link to a historical narrative here, as it calls on Renaissance history. It echoes those traditional, dignified portraits of nobility. This is history made physical through the craft. Do you find the texture adds to that history, or perhaps obscures it? Editor: Oh, I think it amplifies it. Printmaking at this time was becoming much more democratized as a medium—compared to, say, painted portraiture which was largely confined to the very wealthy. Pinssio’s work lets a wider audience access Trivulzio's image, thereby inserting him into a broader social narrative beyond court circles. Think of it as early image circulation! Curator: A crucial shift in cultural dissemination! I see how Trivulzio is portrayed reflects classical realism. It's not just documentation; it aims for idealized likeness—though I do detect some softening of the facial features; do you sense that too, to ensure the person, not just the powerful figure, is present? Editor: Definitely, that’s the power dynamic in action. The material limits and the artist's intent play an important role. The engraving tools constrain Pinssio to using distinct lines, but then his conscious softening adds complexity and gives Gian Giacomo humanity within the stiff bounds of noble representation. I feel the push-pull so much in these choices! Curator: It's fascinating how the print bridges both time and class, the material production becoming another character itself. These old prints hold narratives far beyond their subjects—do you think there's room today to recover similar accessible artistic practices or approaches to how labor is embodied within artwork, beyond conceptual gestures? Editor: It demands constant reassessment. Seeing the labor involved can bring us closer to the actual life of the subject but also towards recognizing artistic contributions inherent in even "lesser" reproductive practices, such as commercial printing methods! Thanks, Gian Giacomo! Curator: Yes indeed, thank you, this historical echo calls us to think about today, about memory and meaning through labor.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.