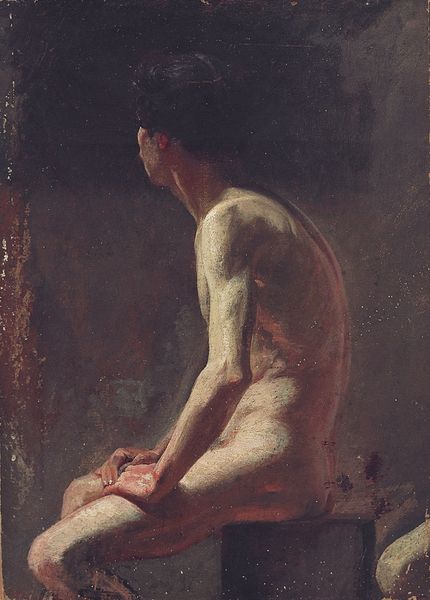

Copyright: Public domain

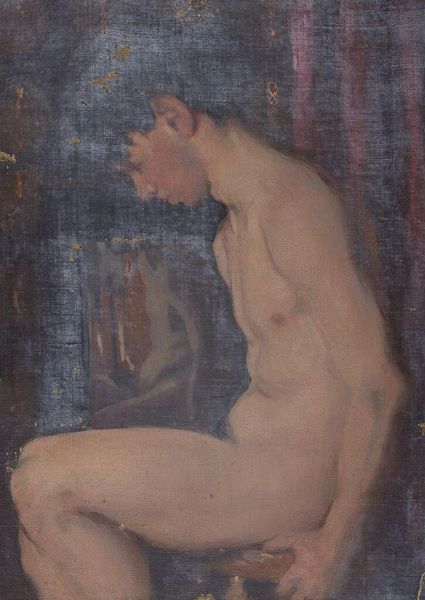

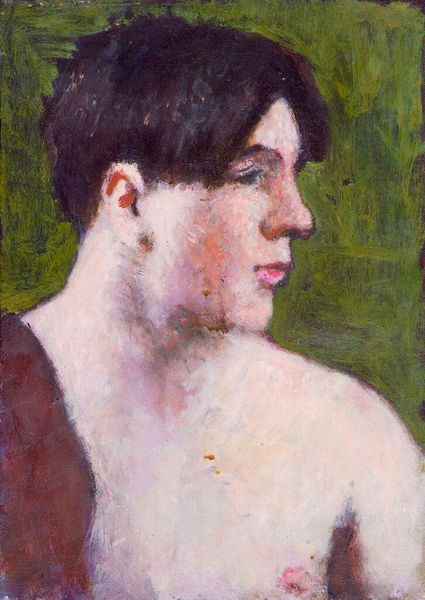

Editor: So, here we have "Back of a Woman" from 1895 by Eliseu Visconti, rendered in oil paint. The soft textures give the skin a tactile quality. What do you see in the making of this piece? Curator: I'm drawn to the physicality of the paint itself, especially the visible brushstrokes that construct the figure. Think about the production of oil paints at the time, the grinding of pigments, the mixing of oils—this wasn't a passive act. Each stroke reflects the artist's labor, their interaction with material reality. The choice to depict a woman's back also subtly directs our gaze, making us contemplate not just the nude form but also the act of looking and the socio-economic forces shaping artistic production at that time. Why the back instead of the front? Editor: That's interesting. I hadn’t considered the social aspect. Maybe it avoids a more direct, potentially controversial engagement? It's like the artist is acknowledging societal constraints on portraying the female form at the time, right? Curator: Precisely. And considering Impressionism's shift toward capturing fleeting moments and subjective experiences, we can also think about Visconti’s methods. What kind of labor went into it? Were these sketches from life that led to a studio piece? And how does the scale impact the viewer's relationship with the artwork? How does the intimate size influence that tactile feeling? Editor: Thinking about the materials and labor involved adds so many layers to my understanding. It moves beyond just aesthetic appreciation. Curator: Exactly. Recognizing art as the result of physical work and social conditions demystifies it, bringing us closer to appreciating it on a more grounded level. What do you take away from it now? Editor: That looking at art through the lens of its production helps connect the artwork to the world. Thanks!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.