Allegorie en drie aanzichten van het lichaam van een eenjarige jongen 1723

0:00

0:00

hieronymussperling

Rijksmuseum

drawing, print, pen, engraving

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

allegory

#

baroque

#

ink paper printed

# print

#

old engraving style

#

figuration

#

child

#

pen-ink sketch

#

sketchbook drawing

#

pen

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 316 mm, width 209 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

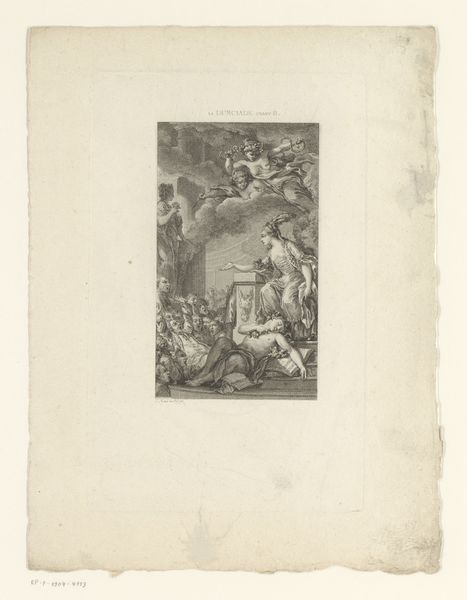

Curator: This engraving from 1723 by Hieronymus Sperling is titled "Allegory in three views of the body of a one-year-old boy." What stands out to you? Editor: My first impression is just how much information is crammed onto one sheet of paper. You have allegorical figures looming over scientific studies of the human form. It's fascinating, almost overwhelming. And look at all that text printed on the page. Curator: The density speaks to the baroque love of layering meanings. Notice how the upper register is replete with symbolic figures: Athena with her shield, a torch-bearer representing perhaps enlightenment, and shadowy figures, maybe alluding to mortality itself? Editor: And below that spectacle, there’s a diagram dissecting the baby’s form. This focus on quantification reminds me how bodies were, and still are, subjected to so much measurement. Even art's not free; the body is viewed here through competing languages of symbol and science. What materials would have been used to make this, by the way? Curator: Sperling created this print using pen, ink, and engraving on paper. This allowed for relatively easy reproduction, which made the ideas contained within more accessible. But beyond pure dissemination, this echoes an older tradition. These allegorical figures are meant to guide our understanding; they stand for more abstract concepts. The radiant child is almost reborn in three stages on the lower half, it has this rebirthal feeling linked to allegories. Editor: Accessible perhaps, though the language barrier poses a challenge. Consider, though, the paper itself, and the economics of printing at the time. This image wasn’t just about aesthetics; it was a commodity, reproduced and sold, playing a role in the cultural consumption of both art and knowledge. The precision with which these diagrams of the child were replicated gives me a sense that it wasn’t the first, second, or tenth piece created, maybe even after multiple re-sharpenings of the tools? Curator: Precisely. That very precision lends authority. This blend of allegory and anatomical study reflects the Baroque period’s interest in revealing underlying truths, be they spiritual or scientific. The image serves as both a celebration of infancy and a memento mori, a reflection on life's fleeting nature. It’s like it is charting not only the boy, but also life as allegory and science at the same time! Editor: A clever weaving-together. The materials here aren't neutral, the ink, paper, and engraving tools used to produce a "commodity" intended for circulation reflect how this vision of childhood was constructed and distributed within 18th-century society. It’s been insightful to connect both meaning and manufacturing. Curator: Yes, understanding the context of production enhances our appreciation. Seeing this engraving as a window into past worldviews and artistic processes definitely helps in how we study and contextualize these Baroque era masterworks.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.