graphic-art, print, engraving

#

graphic-art

#

comic strip sketch

#

light pencil work

# print

#

old engraving style

#

sketch book

#

11_renaissance

#

personal sketchbook

#

sketchwork

#

pen-ink sketch

#

sketchbook drawing

#

storyboard and sketchbook work

#

sketchbook art

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 96 mm, width 82 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

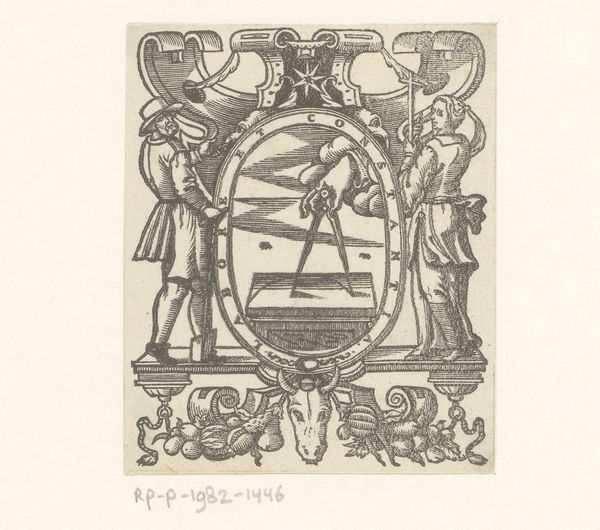

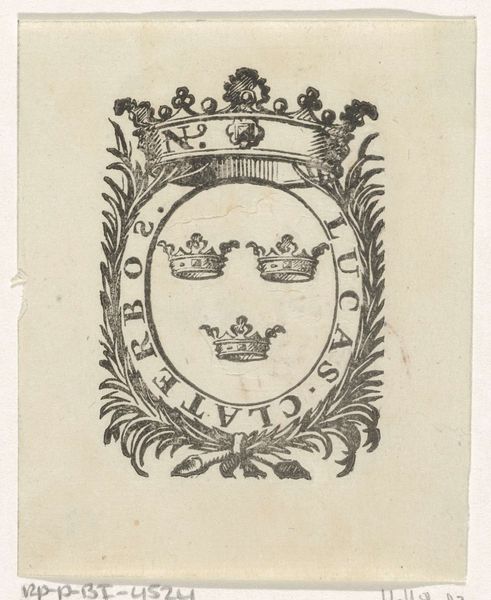

Curator: Immediately striking is the precision and almost mathematical quality of this design. It feels very controlled. Editor: And this is “Ronde cartouche met het wapen van Beieren,” or “Round Cartouche with the Coat of Arms of Bavaria.” Created around 1571 by an anonymous artist, it’s an engraving, a print meant to disseminate the imagery of power. Curator: The diamond pattern in the center is undeniably bold. Do we know what significance it held back then? Was it instantly recognizable? Editor: Absolutely. Those lozenges were and are the Bavarian arms. The engraving serves not just as representation but also a claim, an assertion of ducal or perhaps royal power during a period of shifting political landscapes. Curator: Looking at the delicate linework, especially in the flourishes framing the central image, makes me think about the social role of printmaking at that time. It brings the symbols to people that otherwise may have no idea. Who would see this and how might it influence their understanding of power and hierarchy? Editor: Exactly. Consider this within the broader context of the Reformation, when printed images became powerful tools in shaping public opinion and constructing identity. Even a seemingly straightforward coat of arms participates in that larger cultural discourse. It’s more than decoration; it’s a form of visual propaganda, subtly reinforcing a specific power structure. The "Cum Privilegio" text asserts a legal protection to control the reproduction and therefore distribution of the Bavarian message, too. Curator: So it's a calculated move on the part of the Bavarian ruling class, not merely a decorative object. It’s about visibility, authority and ownership of an idea in early modern society. Thank you. Editor: A small print with big implications for how imagery and identity intersected in 16th-century Europe.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.