#

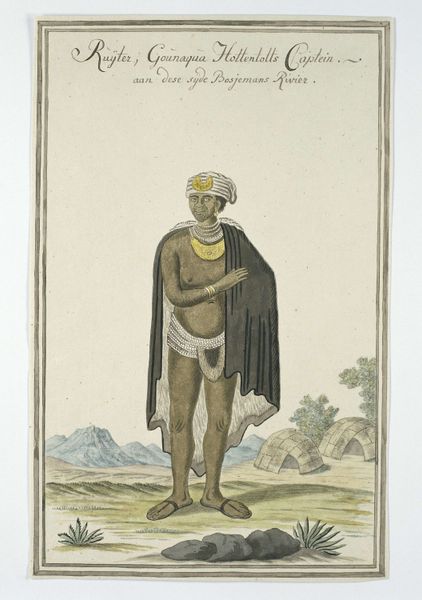

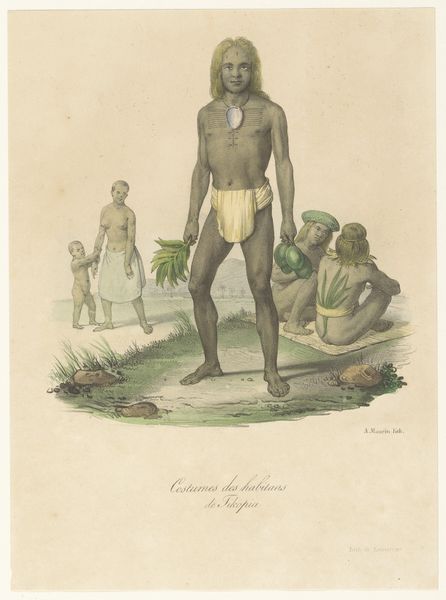

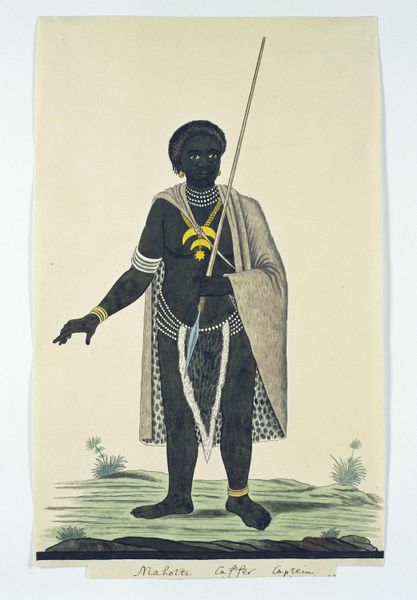

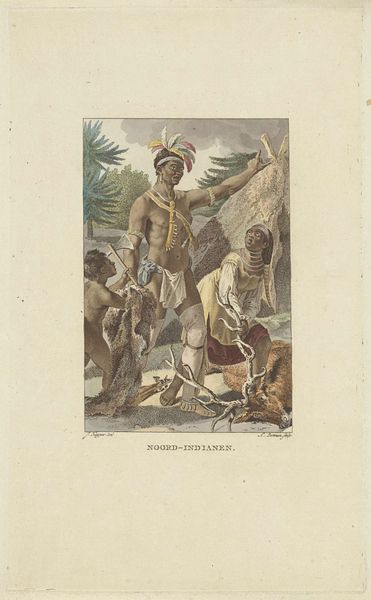

aged paper

#

toned paper

#

yellowing background

#

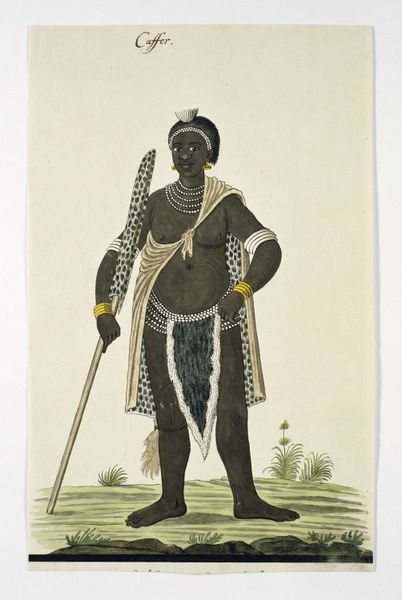

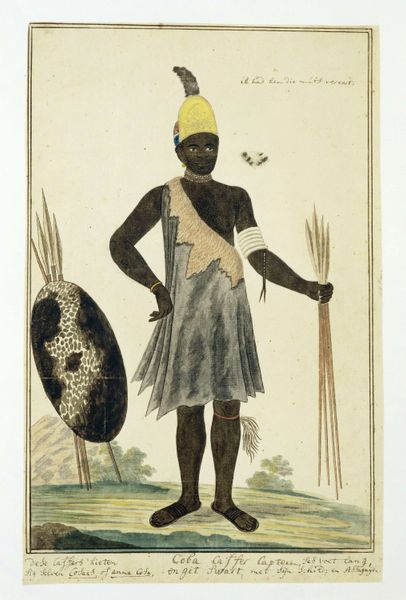

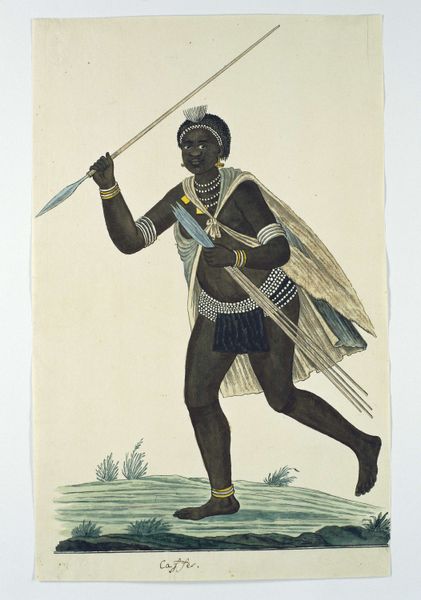

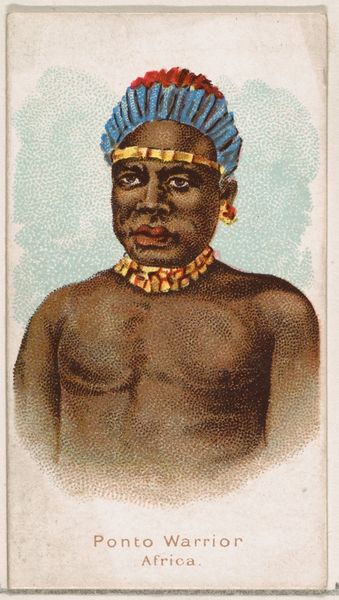

caricature

#

handmade artwork painting

#

portrait drawing

#

watercolour illustration

#

remaining negative space

#

pencil art

#

watercolor

Dimensions: height 660 mm, width 450 mm, height 286 mm, width 189 mm, height 272 mm, width 181 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Let's consider this watercolour illustration attributed to Robert Jacob Gordon, created in 1778. The inscription identifies the subject as “Ruiter, Gonaqua Captein.” Editor: The paper has aged, yellowing with time, giving the portrait a hazy, almost dreamlike quality. The details, like the chieftain's gold adornments and the cape, strike me with an almost jarring juxtaposition against what seems like a pencil sketch of the man’s body. Curator: Indeed. Gordon, a military commander in service of the Dutch East India Company, wasn't formally trained as an artist, though it was common for people to produce drawings when traveling because photography wasn't yet available. Editor: The visual evidence here emphasizes how materials of trade became materials of representation. The detail applied to depicting things of obviously high value clashes against the rather flat rendering of the man’s figure itself. Curator: Precisely, that imbalance speaks to the colonial gaze. The focus on adornments, which were traded between settlers and the indigenous population, highlights what colonizers valued and considered important, thus telling a specific story of colonial contact. Editor: It makes you wonder about the circumstances of its creation. The way the light falls… it is less of a true portrait and more like a symbolic inventory, of sorts. Curator: Portraits of indigenous leaders were used to assert authority and solidify narratives around colonialism. These images served as documents, justifying their presence and influence. Ruiter's calm posture contrasts the implicit power dynamics at play. Editor: So, the visual choices emphasize the colonizer's agency and the objectification of indigenous peoples within those emerging power structures. Looking at it now, one can feel the tension embedded within these artistic decisions, how the materiality reflects the exploitative social context of the time. Curator: Yes, understanding this historical context allows us to understand art as cultural records—objects with ideological purpose beyond their surface aesthetics. Editor: It’s a striking reminder that art isn’t created in a vacuum. Examining the work in these historical and material terms opens the work to critical discussions that otherwise are invisible in it.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.