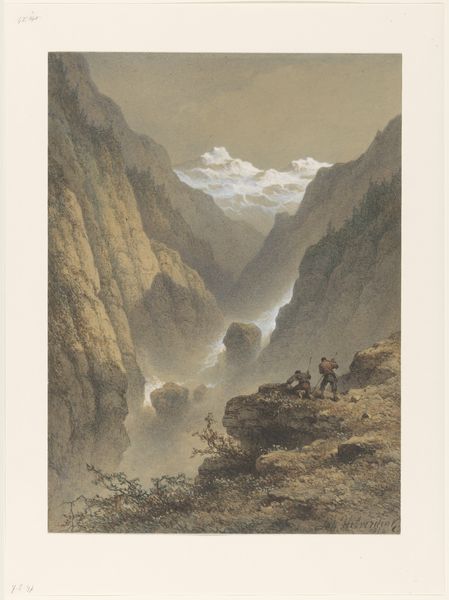

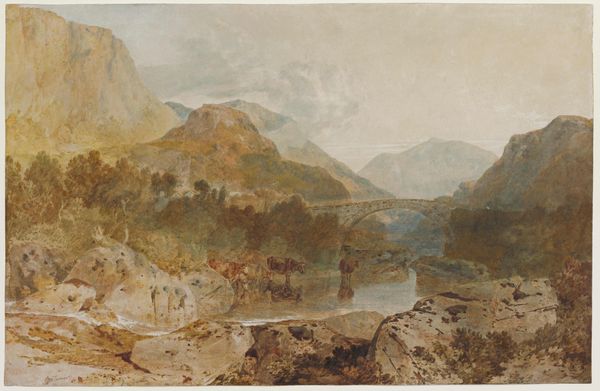

drawing, painting, plein-air, watercolor

#

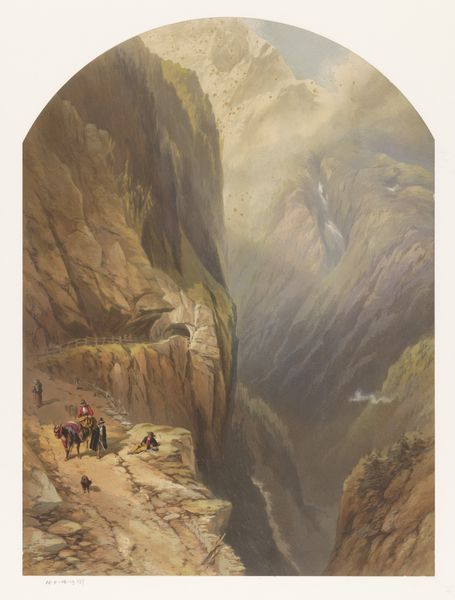

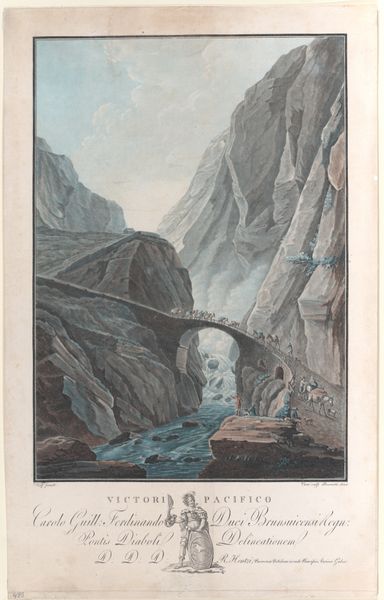

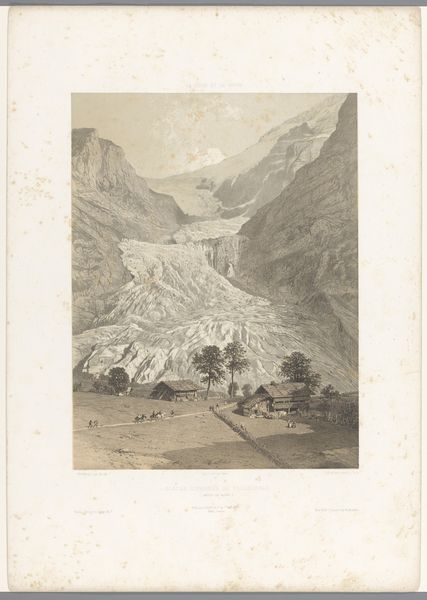

landscape illustration sketch

#

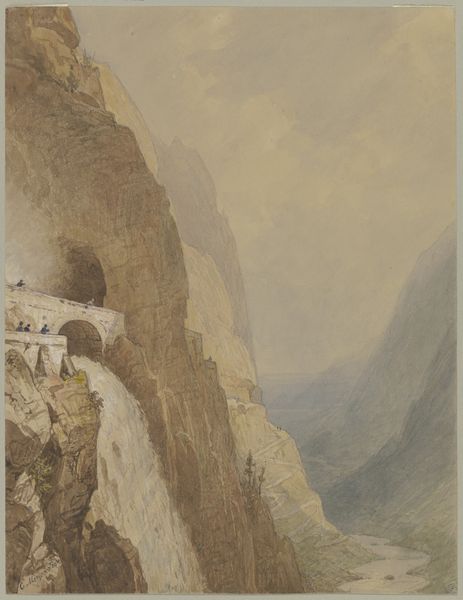

drawing

#

painting

#

plein-air

#

landscape

#

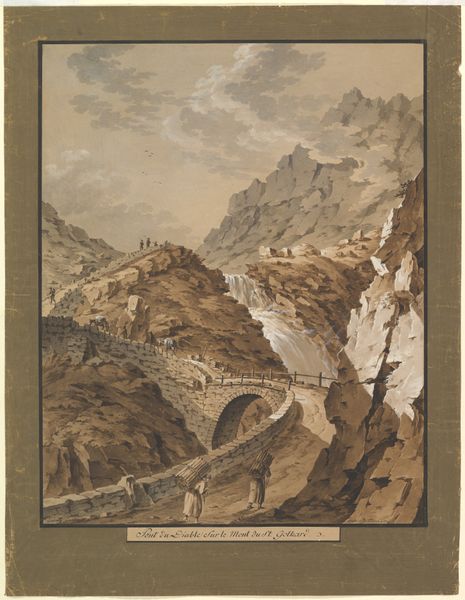

watercolor

#

romanticism

#

watercolor

Dimensions: overall: 33.4 x 23.3 cm (13 1/8 x 9 3/16 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

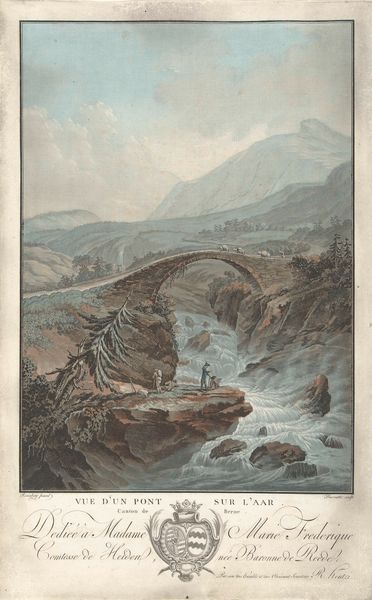

Curator: At first glance, the overall palette feels muted, almost sepia-toned. The composition leads my eye directly towards those craggy mountains in the background. There’s a sense of scale and timelessness here. Editor: Exactly. Let’s unpack that timelessness. What we have here is “Pont Aberglaslyn,” a watercolour painted around 1812 by John Varley. The location, as the title suggests, is the Aberglaslyn Bridge in North Wales. Varley, a prominent figure in the Romantic movement, frequently depicted British landscapes. Curator: Setting, bridge, the little figures upon it—it’s almost stage-like, prompting me to wonder about the accessibility, not just physically, but culturally of these landscapes to ordinary people. Was landscape appreciation solely the domain of the wealthy? What role did depictions like these play in democratizing it, or perhaps, romanticizing access? Editor: That’s a sharp observation. Certainly, by the late 18th and early 19th centuries, there was a growing popular interest in landscape, fueled by the picturesque movement. Prints and paintings became more affordable, extending beyond aristocratic patronage to reach the emerging middle class. Artists such as Varley were tapping into this desire. Simultaneously the location and imagery may be less accessible to anyone outside white social circles. Curator: Absolutely, it raises critical questions of inclusion. Who is missing from these images, who's labor helped sustain it, and how can we reclaim those absent narratives? It's vital that galleries actively confront these occlusions when we talk about art like this today. Editor: Absolutely. Moreover, let's also consider Varley's choice of watercolour, it's a quick medium suited to plein-air sketching, which made this a democratic and mobile tool. Curator: So, whilst acknowledging the problematic framing inherent in the consumption and production of the aesthetic qualities we could look toward new perspectives offered via accessible processes? A kind of critical yet appreciative gaze? Editor: Precisely. The layers of history inform how we interact with such scenes—and it falls on museums to help audiences question, engage, and, perhaps, reshape our perception of the British landscape itself. Curator: I think, reflecting, this work challenges me to delve more critically into what landscape meant during that time and to advocate for inclusivity.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.