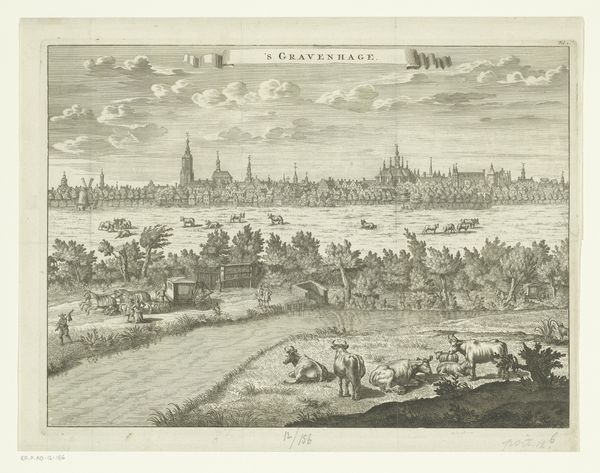

print, engraving

#

baroque

#

dutch-golden-age

# print

#

landscape

#

perspective

#

line

#

cityscape

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 162 mm, width 193 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This delicate engraving, titled "Gezicht op Dokkum," offers a fascinating look at the Dutch cityscape through the eyes, and hands, of Jacob Folkema. It dates somewhere between 1702 and 1725. Editor: It's remarkably intricate, isn’t it? Even at this remove, you can feel the labor etched into those lines, that exhaustive depiction of a landscape, like a record, an inventory… the wind power made visible through the iconic windmills, it feels… almost industrious. Curator: I'm drawn to the symbolic language layered throughout. Consider the banner at the top; "DOKKUM," emblazoned, and then that crown and crescent moon… signs that spoke to power, civic pride, perhaps even a hint of regional identity that would be so crucial for the later Netherlands. Editor: The lines are what captivate me—it’s almost architectural in its precision. Look at the rendering of the wall protecting the town and the layout, its almost mathematical... And the animals that occupy the foreground appear to be more like props placed strategically rather than a free depiction of reality. I wonder what materials he had, who commissioned the piece, how many prints were struck from the plate… it feels almost mass-produced, which I find unsettling Curator: But within those rigid lines, there's also a clear effort toward representing depth and perspective. See how our eye is led back toward the center of Dokkum, and that play with foreground and background! The engraver gives you an impression of this space that, in turn, speaks about the relation that men have with it. Editor: Which is something crafted through a very laborious process. You can see how the land itself, and even labor of depicting the land, can itself become something bought and sold, displayed, consumed… it reminds us the extent to which value is generated by physical toils of both the natural environment and our activity within it. Curator: Exactly! The composition encourages us to reflect on civic life but also that rural atmosphere. Perhaps in an almost didactic way. Editor: I think it serves as a reminder how images are essentially fabricated… How images require work and, in themselves, transform our relationship with the world that we inhabit and share. Curator: I see it more as a testament to the power of imagery to evoke, even across centuries, the values that shaped this small, but essential Dutch city.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.