Dimensions: height 80 mm, width 112 mm, height 314 mm, width 450 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

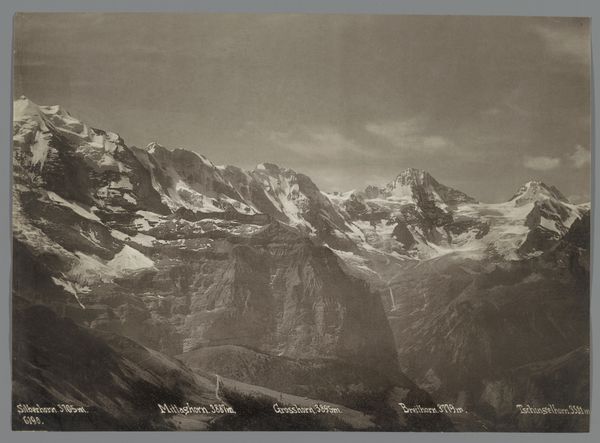

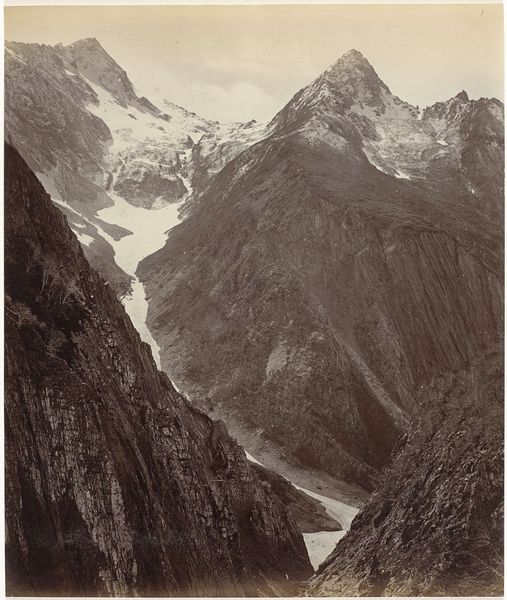

Curator: Before us, we have "Uitzicht over een berglandschap en zee" – "View over a mountain landscape and sea"— a gelatin-silver print created by Paul Güssfeldt in 1889. It immediately evokes a feeling of vastness, doesn't it? Editor: It does. A sort of romanticized sublime, tinged with sepia melancholia. I'm curious about the albumen process that yielded this toned effect—it really speaks to a particular photographic material aesthetic. Curator: Güssfeldt’s romanticism isn’t just about aesthetics, though. Think about the colonial era: what narratives were being constructed about nature, about exploration, and who had access to these 'views'? The 'discovery' and claiming of landscapes always comes at a human cost. Editor: That's where the story in the image lies; it's an incredible use of a burgeoning medium, capturing a manufactured ideal of conquest. One might not recognize such high-level photographic technology was applied at the time to make such records; considering the accessibility of cameras these days it’s all too often forgotten that one needed significant financial and technological access to the machinery involved. Curator: Exactly. This photograph becomes less about the beautiful scenery and more about power, access, and the politics of representation, who could view, who could photograph, and whose perspectives were erased in the process. The fact this view can be mediated through Güssfeldt's lens invites interrogation. What are the power dynamics present in simply viewing an image? Editor: It brings to the surface some important discussions to be sure. From my vantage point, looking at the print, it seems like Güssfeldt put a significant amount of effort into achieving very specific monochromatic tonalities via chemical controls in the photo development and printing, making for an ideal aesthetic for commercial consumption that was simply unavailable through, say, a charcoal drawing or watercolors. The man wasn't simply taking a snap and recording a beautiful landscape. He knew exactly what he was doing to the photo materials, in order to appeal to customers to generate income for the sake of both capitalist enterprise, and technological exploration into these processes. Curator: It is important to consider that Güssfeldt wasn’t merely pointing a camera. The photograph became a tool to frame and possess that landscape, reinforcing specific cultural narratives and erasure of other voices, perhaps people that already lived within the frame captured. Editor: Yes, I agree entirely; reflecting on this process, the social layers become clear, a good reminder that even the tools themselves have political implications.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.