Copyright: Public Domain: Artvee

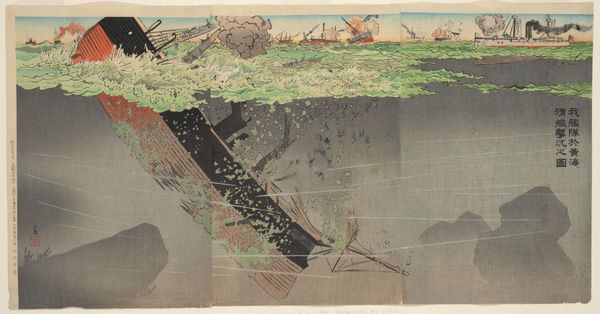

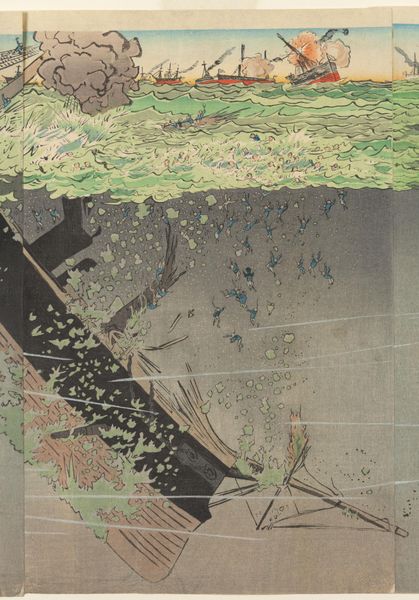

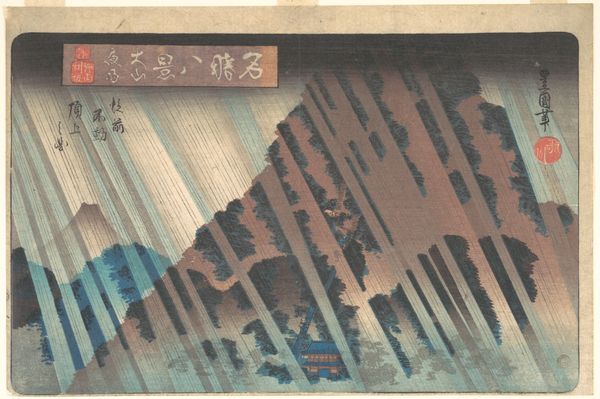

Curator: Here we have Kobayashi Kiyochika's woodblock print, "Our Navy Sinking a Chinese Warship in the Yellow Sea," created in 1894. It depicts exactly that: the heat of battle during the First Sino-Japanese War. Editor: My first impression is the overwhelming sense of chaos. The ship is being violently consumed by the sea, and there's so much frantic energy in the waves and the spray. Curator: It’s propaganda, make no mistake. Kiyochika was employed to produce images celebrating Japanese victories. Ukiyo-e prints were often used for these kinds of narratives for a wider public audience. How do you interpret that in terms of its societal function at the time? Editor: Well, considering Japan was rapidly modernizing and flexing its imperial muscles, this image served to legitimize its actions. It presents war as almost heroic, obscuring the suffering and human cost involved, creating a collective identity. This is a visual rhetoric to build national unity. Curator: Absolutely. Look how the artist utilizes western watercolor techniques—specifically the 'watercolor bleed' effect which adds to the dynamism, creating movement while embracing that new influence. This shift in style reflected Japan's broader embrace of western advancements to bolster its position. It raises questions, doesn’t it, about artistic appropriation within asymmetrical power dynamics. Editor: Indeed. While ostensibly celebrating Japan's progress, it’s critical to remember this progress was achieved, in part, through violence and exploitation. Who benefits from this story and at whose expense? The narrative becomes even more complex when considering the print as an accessible, consumable commodity—art becoming a vehicle for shaping public sentiment. Curator: It also prompts questions about national identity, gender and race, which became strategically manipulated for state objectives. What did it signify, for instance, to the viewers to have “their” navy destroying a warship of China, coded racial otherness? Editor: The historical specificity matters immensely, and unpacking it challenges us to resist simplistic notions of heroism. The work reveals uncomfortable truths. Ultimately, that print acted as a mirror—reflecting back to Japanese society its aspirations and its anxieties within this evolving world order. Curator: And today, hopefully prompts critical self-reflection on the lingering impact of such visual messaging and how power dynamics continue shaping narratives.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.