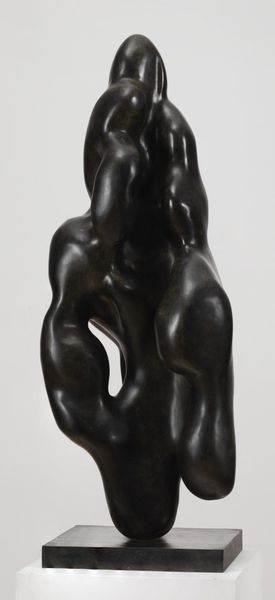

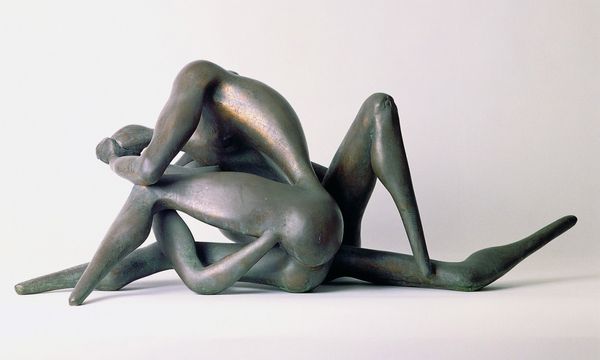

Dimensions: object: 590 x 240 x 250 mm

Copyright: © The estate of Alan L. Durst | CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 DEED, Photo: Tate

Editor: Here we have Alan Durst's wooden sculpture, "The Acrobats," housed here at the Tate. It has a really intriguing, blocky quality. What do you make of this piece? Curator: Well, considering Durst's lifespan, the sculpture probably reflects a broader fascination with the body's capabilities seen across Europe in the early 20th century. Does it make you think of similar themes in other art forms of that period? Editor: I see hints of theatrical performance and the representation of the body in art. But I’m curious, how does the sculpture's presence within the Tate collection influence our understanding? Curator: The Tate's acquisition itself is a statement, placing "The Acrobats" within a lineage of British sculpture, impacting its historical narrative and public reception. It’s a question of how institutions shape meaning. Editor: That’s fascinating. I didn't consider how its location could recontextualize the work. Curator: Exactly! It reminds us that art exists not in a vacuum, but within a network of power, display, and interpretation.

Comments

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.

tate 9 months ago

⋮

Durst was one of several artists who looked to African art in order to revitalise modern European sculpture. The unusual arrangement of figures in The Acrobats allowed him to adopt elements that were typical of West African carvings, notably the buckled, stocky legs. Durst would have seen African carvings in the British Museum and in private collections (the Baga figure in the nearby vitrine once belonged to the sculptor Jacob Epstein). These examples also encouraged him to adopt ‘direct carving’ as a more authentic method of self-expression. Gallery label, July 2008