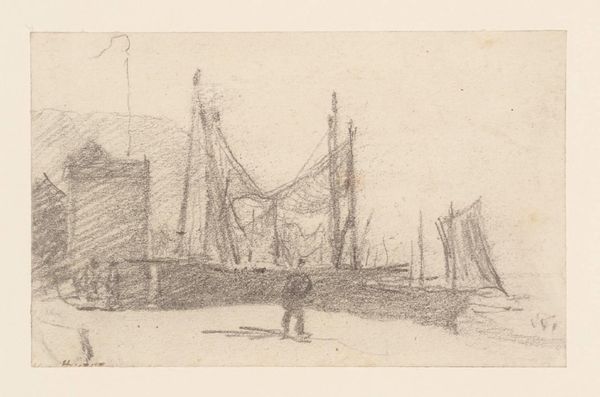

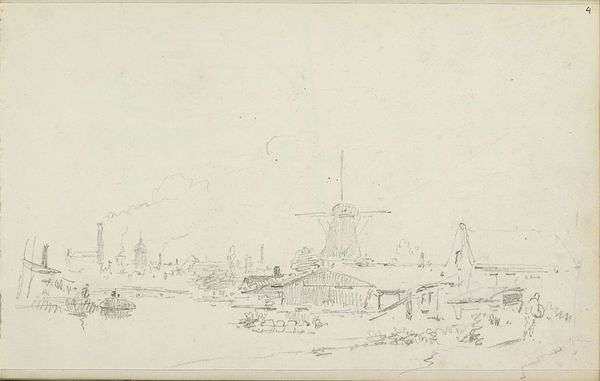

drawing, pencil

#

drawing

#

landscape

#

romanticism

#

pencil

#

cityscape

Dimensions: height 110 mm, width 172 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

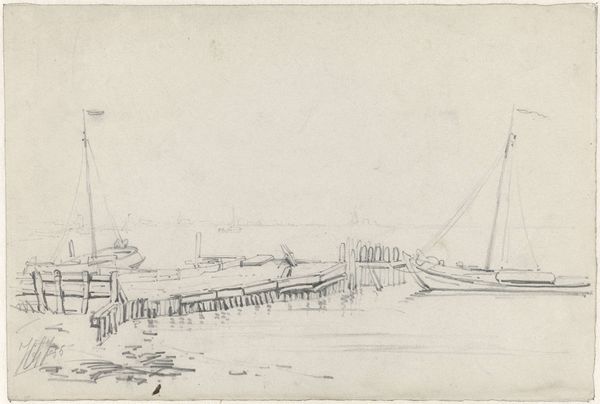

Curator: Eugène Isabey's pencil drawing, "Molens aan de haven van Rotterdam," likely created between 1813 and 1886, offers us a glimpse into the port of Rotterdam. It's currently housed in the Rijksmuseum. Editor: It's...evocative. Bleak, almost. There’s a real sense of industry meeting nature, but it feels heavy, somber. The limited use of line makes everything feel transient, as though it might all disappear any minute. Curator: Exactly. Look at how the pencil is applied: a frenetic hatching capturing both the industrial elements and the natural waterways. Isabey, steeped in Romanticism, emphasizes texture through minimal means. Editor: This work captures a society in transition, grappling with modernization. We have these antiquated windmills juxtaposed with emergent industry represented by the ships’ masts and maybe even smoke stacks. The materiality—pencil on paper—speaks volumes. Curator: True. Pencil was relatively inexpensive and easily accessible, making sketching, and this type of artistic practice more broadly, part of middle-class life. So in one sense, we are encountering both a shift in representation and access. It is worth considering where his pencils may have come from as well; its material origins potentially woven with colonial extraction. Editor: Absolutely. The composition directs our gaze to how Rotterdam negotiated these emerging capitalist systems. We’re considering waterways of both commerce and necessity. We cannot ignore that waterways frequently delineate social classes. Who is doing the labor? Curator: Indeed. The drawing asks us to observe a fleeting moment in this maritime culture: its structures and, importantly, its laborers, even though they are invisible. Editor: Which reinforces my initial point. Even the architectural reflections feel uncertain, alluding to displacement. It is critical that we view such serene landscape drawings within social contexts of production. This way we remember what the drawing omits and, ultimately, what the Industrial Revolution cost so many marginalized people. Curator: Precisely. So a seemingly simple sketch carries so much material and political history. Editor: Well said. I’m glad we’ve given our listeners ways to read it that engage in the human element as well.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.