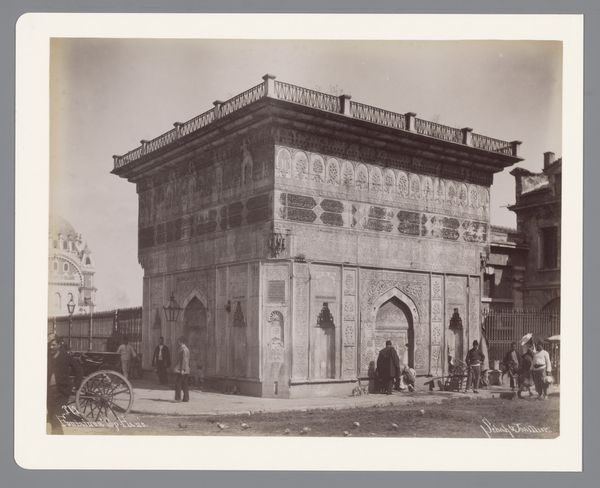

photography, gelatin-silver-print, architecture

#

landscape

#

photography

#

orientalism

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

19th century

#

islamic-art

#

architecture

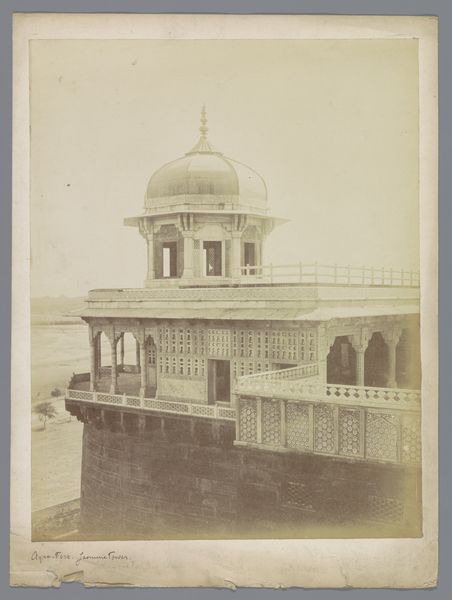

Dimensions: height 216 mm, width 281 mm, height 238 mm, width 316 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

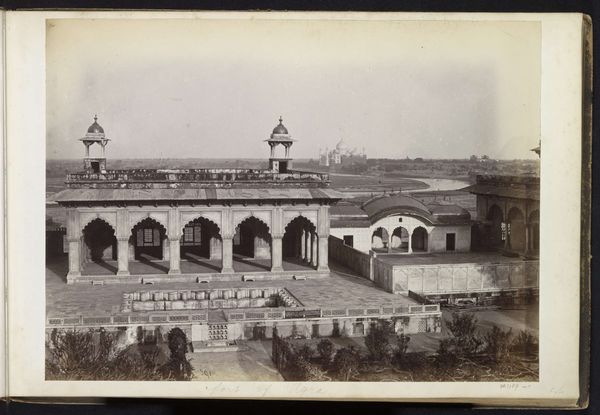

Editor: This is Samuel Bourne’s “View of the Panch Mahal at Fatehpur Sikri, Uttar Pradesh, India,” a gelatin-silver print dating from the 1860s. The architecture has this incredible, almost dreamlike quality in this hazy sepia tone. What historical layers am I missing here? Curator: This image, like much Orientalist art, invites us to unpack its complex relationship with colonialism. Bourne was a British photographer working in India during the height of British colonial power. The Panch Mahal itself was built during the Mughal Empire, representing a fusion of Persian and Indian architectural styles. What do you make of Bourne choosing this specific structure? Editor: Perhaps its visual distinctiveness appealed to him, as something exotic and worthy of documentation. Curator: Precisely, but it goes deeper. Bourne wasn's simply documenting; he was framing, composing, and interpreting. Consider who this photograph was intended for: a Western audience. Images like this reinforced a certain narrative about the East as ‘other,’ exoticized, and ultimately, something to be possessed or controlled, even subtly. Editor: So, Bourne's work, even seemingly objective landscapes, contributed to a broader political agenda? Curator: Absolutely. By emphasizing the grandeur of Mughal architecture while remaining silent about the socio-political realities of British rule, he created a selective, and ultimately, skewed view of India. Consider how the lack of human presence in the photo emphasizes the architectural monumentality. Editor: It really does make the building feel frozen in time, divorced from its context. I guess I hadn’t thought about how much a landscape could reflect power dynamics. Curator: It's a crucial point. These images weren't neutral; they were active participants in shaping perceptions and justifying colonial projects. Now, looking at it again, does the image speak differently to you? Editor: It does. I’m now a little more aware of whose gaze is privileged and who or what gets erased in the process. Thanks for this. Curator: My pleasure.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.