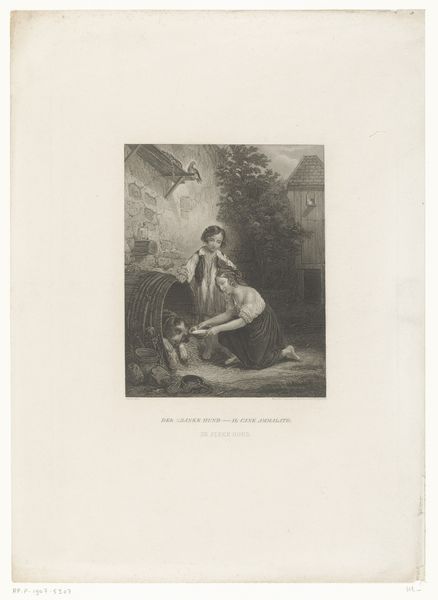

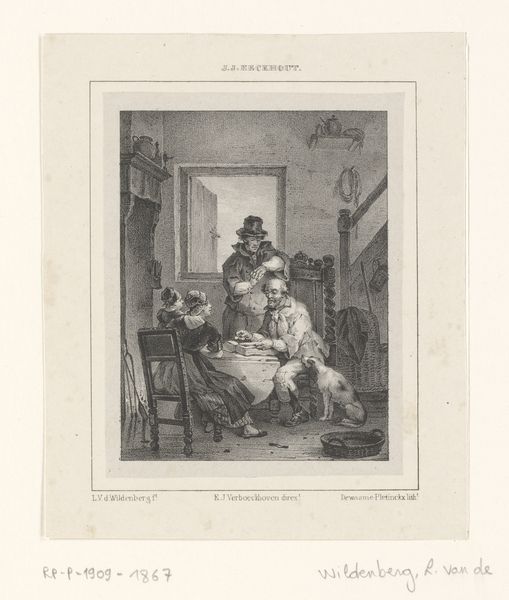

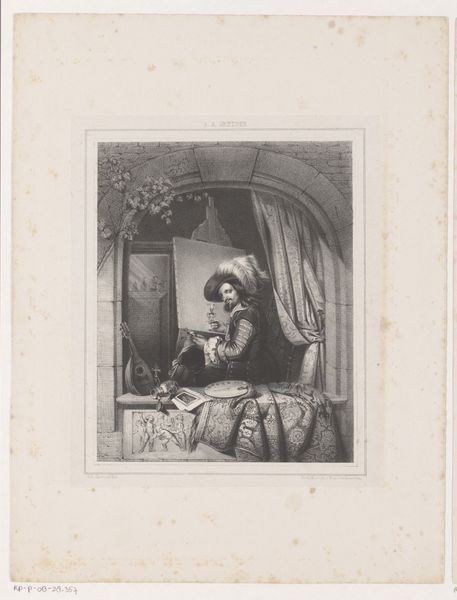

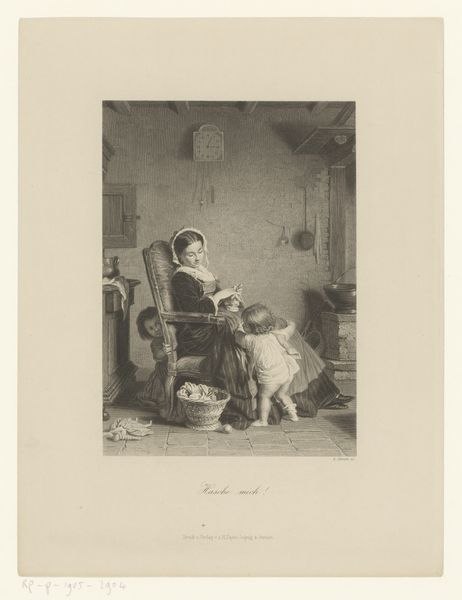

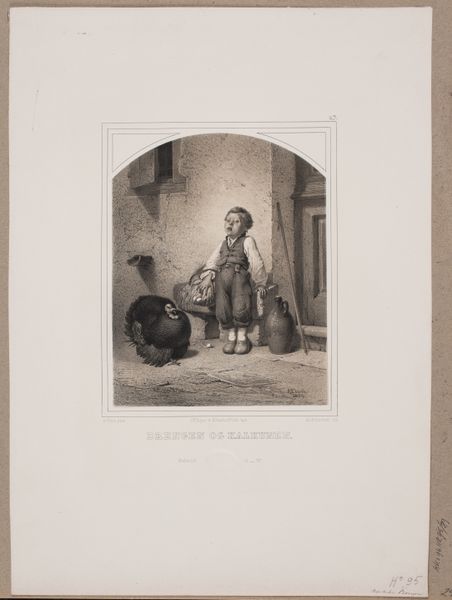

print, paper, engraving

#

portrait

# print

#

landscape

#

paper

#

genre-painting

#

engraving

#

realism

Dimensions: height 251 mm, width 217 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have "Meisje in een schuur met dieren en een kitten in haar armen," a print, likely an engraving on paper, from 1834, credited to George J. Zobel. The scene feels very intimate, a glimpse into daily life, and there's a tenderness in the girl's expression. What do you see in this piece? Curator: What strikes me is how carefully the artist constructs this image to represent innocence and domesticity, yet it is also clearly designed for a public audience. We see a genre painting made accessible through the medium of print. Think about who could afford art. The print makes art available to many. Who were the audiences consuming such images, and how might this influence their perceptions of rural life and childhood? Editor: That's interesting. I hadn't thought about who would have been viewing it originally. So the art's public role at the time was key? Curator: Absolutely. Consider the institutional and social contexts: prints like these were often reproduced in magazines and books, disseminating ideas about gender, class, and national identity. Were such scenes of childhood intended to promote certain virtues or reinforce social hierarchies? Are we idealising rurality? Note the interior: It speaks to the daily grind. Editor: So, beyond the surface sweetness, it's presenting something more about society? Curator: Precisely. By analyzing this artwork within its historical and cultural context, we gain insight into the values, power structures, and ideologies circulating at the time. Think about what stories this print helped tell, and what roles the public played in perpetuating or challenging them. Does the sweet girl mask labour and potential issues with gender roles at the time? Editor: I guess, viewing it like that really reveals much more than first meets the eye. It moves beyond face value. Curator: Indeed. Art doesn't exist in a vacuum; it reflects and shapes the society that produces and consumes it. That’s a print, right? In the Victorian times that might mean cheaper production rates, meaning maybe these images ended up anywhere! From children’s annuals to pamphlets of all kinds. We must ask ourselves where it sits within a historical context.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.