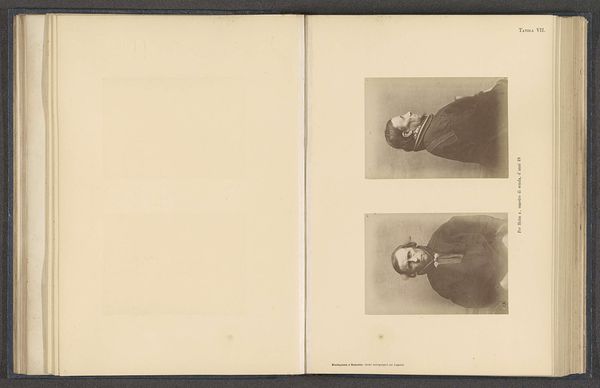

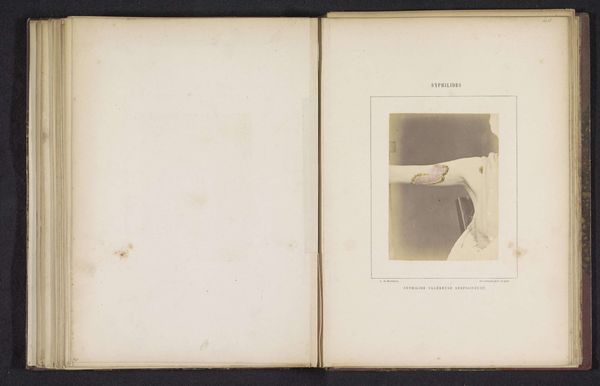

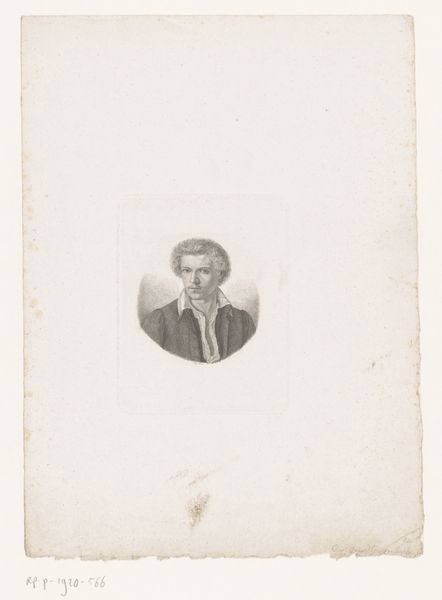

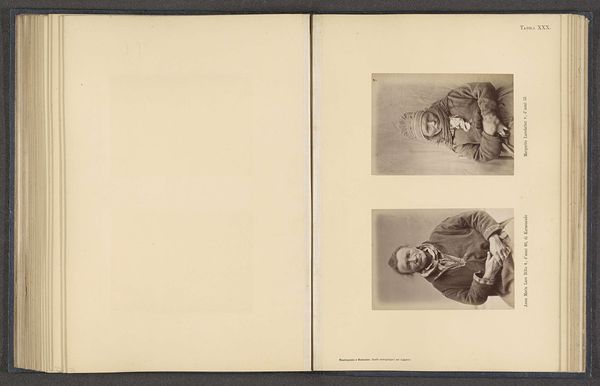

Portret van een onbekende man met zweren in zijn gezicht, mogelijk veroorzaakt door koningszeer c. 1860 - 1868

0:00

0:00

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

aged paper

#

script typography

#

hand drawn type

#

photography

#

hand-drawn typeface

#

fading type

#

stylized text

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

thick font

#

white font

#

handwritten font

#

realism

#

historical font

Dimensions: height 120 mm, width 90 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: So, here we have a gelatin-silver print from around 1860 to 1868, titled "Portret van een onbekende man met zweren in zijn gezicht, mogelijk veroorzaakt door koningszeer," attributed to A. de Montméja. The starkness of the portrait, combined with the visible suffering, is immediately striking. What’s your take on this image? Curator: I see this portrait first and foremost as a document, a material record of a specific social and medical condition. It reveals as much about the production of images and photographic practices of the time, as it does about the sitter’s suffering. Royal evil, or scrofula as it was then known, was associated with poverty and class. It is hard to imagine portraits like this being commissioned of members of wealthy elites. Who was producing these portraits, and for what audience? What social role does it play to portray certain subjects as being afflicted? Editor: That’s a really interesting point about who the portrait serves. Were these types of medical portraits commonly commissioned? Curator: Precisely, this work might be an instance of documentation that was commissioned or initiated from an external position, not intended for domestic, familiar or aesthetic viewing. Who produced it, and how and why might have informed the production choices. Looking closely, you see the photographic material itself has aged, with noticeable fading and imperfections, serving as a kind of physical witness to the passage of time and historical conditions. Editor: So, the aging process of the print itself adds another layer to the narrative, reflecting the effects of time on both the subject and the artwork itself? Curator: Exactly. And the "thick font" hand-drawn typeface on the print suggests a standardization process, possibly for scientific or medical records. This element suggests the context is less fine art and more utilitarian record-keeping of individuals subjected to such suffering during this era, something closer to a government census of disease. What this means for contemporary interpretations and cultural impacts of the portrait, remains. Editor: That reframes my view completely. I was initially focused on the individual's suffering, but now I see how the materials and context give us a much broader understanding of society. Curator: I’m glad you find new paths for interpretation of a unique portrait. Considering that, my role as the Curator ends here.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.