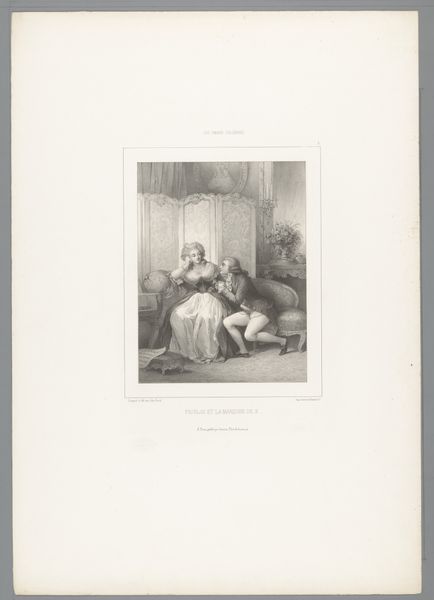

etching

#

etching

#

intimism

#

romanticism

#

genre-painting

#

nude

Dimensions: height 552 mm, width 360 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

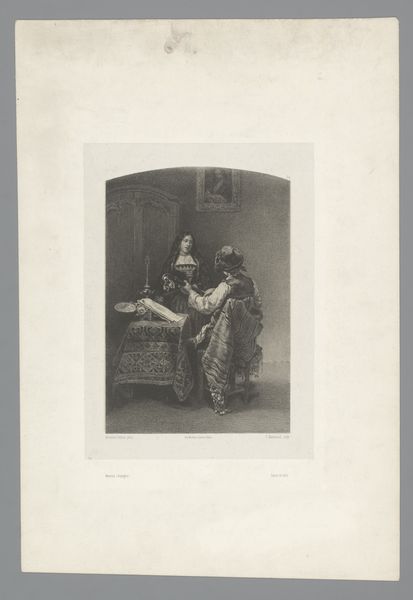

Curator: Before us is Jean-François Gigoux’s etching from 1832, titled "Dorpsmeisje kleedt zich 's ochtends aan"—in English, “Village Girl Dressing Herself in the Morning." Editor: My first thought is, there's something immediately intimate and private about this scene, captured in monochromatic tones. It’s not overtly sexualized, but there is definitely a sense of observation. Curator: Precisely. Genre scenes like this became popular, offering glimpses into everyday life. What’s interesting is how Gigoux presents this “village girl.” Is it an authentic representation, or is he playing with certain tropes for an urban audience? The artwork highlights a moment of quiet vulnerability, which arguably emphasizes her lack of status. She is caught in the act of dressing, vulnerable, and open to interpretation. Editor: Considering that Romanticism celebrated emotional intensity and often idealized rural life, I wonder if Gigoux is tapping into a similar vein, positioning the village girl as somehow purer or more connected to nature. Of course, it also suggests a class dynamic where her privacy and personal space are not inherently protected. She is observed in this small space, caught in a vulnerable act of dressing. We are implicated as observers, whether we choose to be or not. Curator: Her surroundings provide a clear distinction to bourgeois norms; her intimate act contrasted against what could be constructed as rural squalor. Considering Romanticism as a rejection of industrial modernity, is Gigoux constructing a critique of modernity itself? The act of gazing itself carries societal and historical power. Whose gaze is prioritized in art history? How does this reinforce specific social hierarchies? Editor: Right. This image begs questions about the politics of looking. The "gaze," as discussed by feminist theorists like Laura Mulvey, exposes how the art historical tradition is male and heteronormative. This creates the power dynamic in the scene, turning this girl into an object of aesthetic consumption, potentially at the cost of stripping away any genuine respect. Curator: It makes you consider, who really benefits from these portrayals of the vulnerable? Do they empower, or merely perpetuate certain social orders? Editor: This single etching invites questions about agency, representation, and the complicated dialogue between art, society, and the viewer. Curator: A quiet, private scene, amplified through socio-historical lenses—making us confront uncomfortable but crucial issues.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.