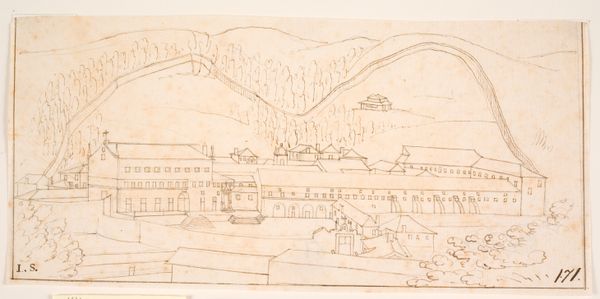

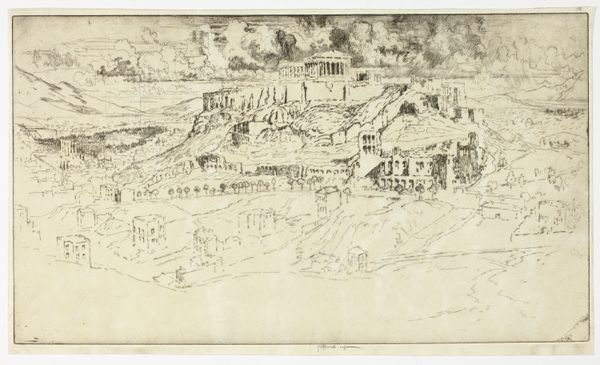

drawing, paper, ink

#

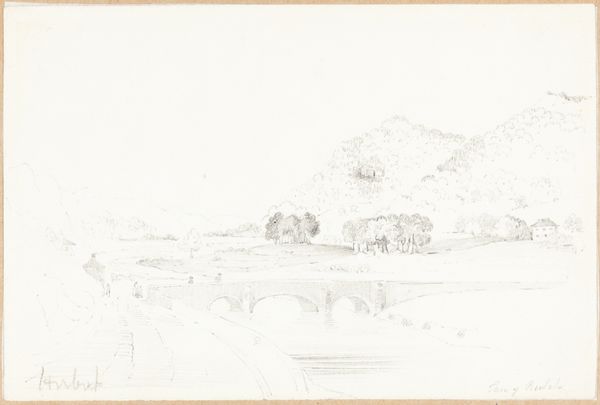

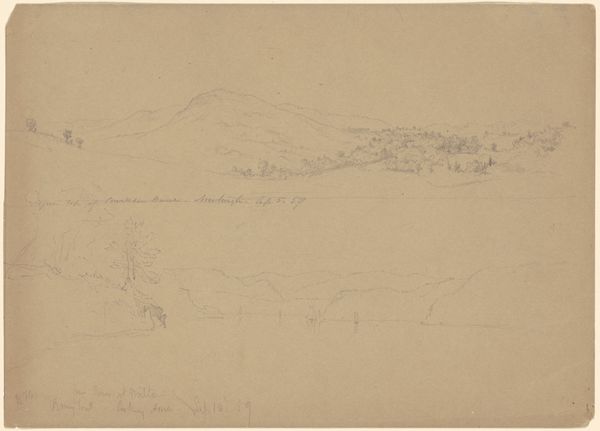

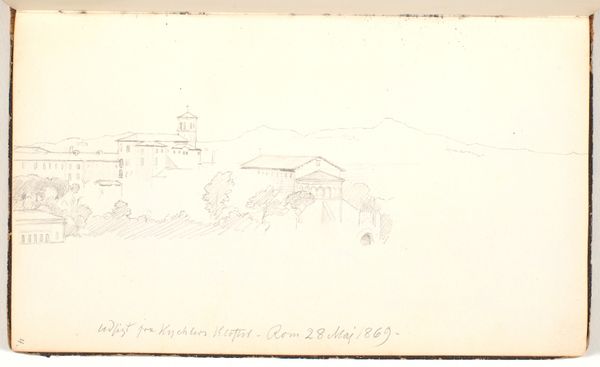

drawing

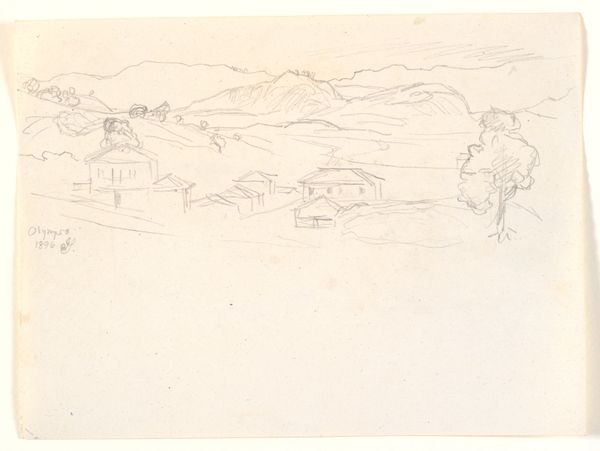

#

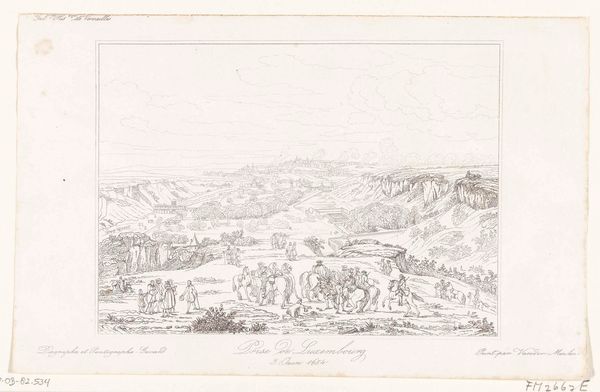

landscape

#

paper

#

ink

#

romanticism

#

realism

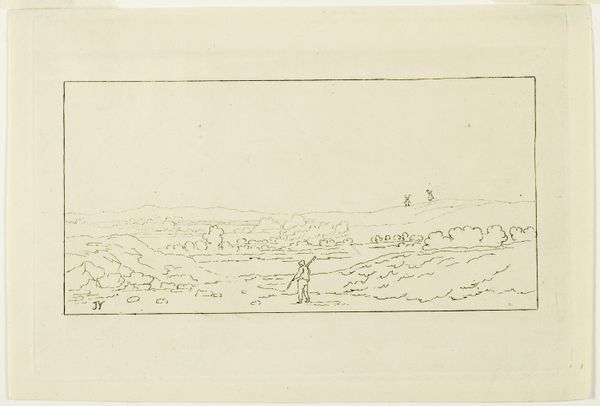

Dimensions: 115 mm (height) x 220 mm (width) (bladmaal)

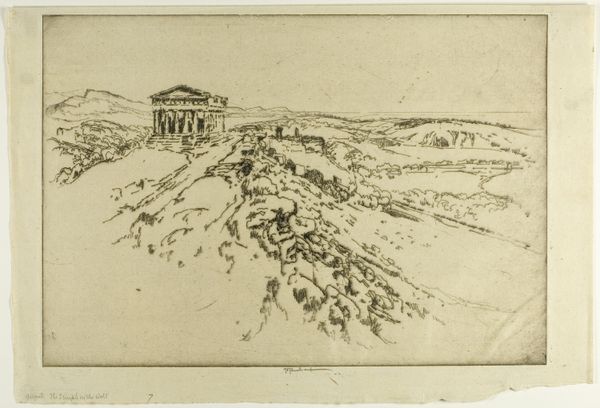

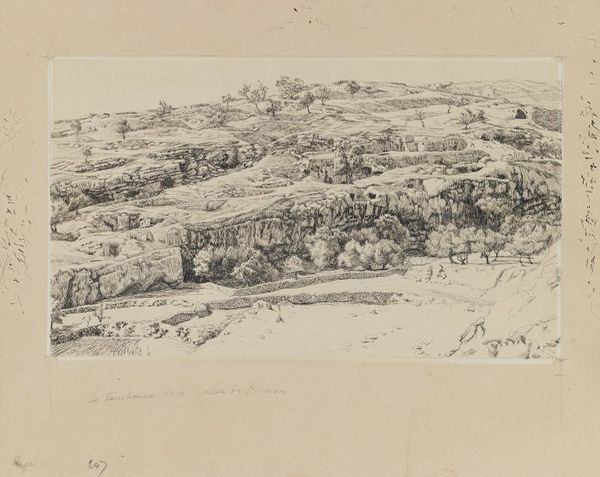

Curator: Martinus Rørbye’s drawing, "Vicino di Cicilia Metella," created in 1837, is rendered in ink on paper. What's your initial take on it? Editor: Well, the sepia tones lend it an antique quality. There's something both serene and melancholy in the open composition and use of line; a stark contrast that adds a great depth of feeling. Curator: It’s a beautiful example of how landscape depictions can tell stories far beyond their literal scenery. Sicily during the 1830s was a site of immense political and social turbulence. Bourbon rule was faltering, and nationalist sentiments were intensifying. I see in this drawing Rørbye’s awareness of this transitional period, reflected in the lone figure near the center. Editor: I see what you mean about the political context. I am compelled by how he has used lines—some firm and assertive, others incredibly light—to articulate structure. Take, for example, the treatment of the distant structures or temples; they seem solid but at the same time appear to fade as they approach the horizon. It’s an exquisite balancing act between the tangible and the ephemeral. Curator: Absolutely. Romanticism thrived on paradoxes. On one hand, there was the artistic embrace of historical grandiosity, as expressed in the ruined buildings Rørbye chose as a motif here. Yet on the other hand, it conveys this very intimate understanding of vulnerability felt by ordinary individuals, represented by this singular figure dwarfed by monumental historical change. Editor: Indeed. This resonates within me now. Curator: Looking at Rørbye’s historical position as an artist moving through the era, it provides a visual case study for analyzing identity and the burden of legacy. Editor: Seeing your focus on historical implications makes me rethink the depth of the architectural structures he depicts. It’s no longer merely an aesthetic feature; instead, they stand as markers of past societies, perhaps even hinting towards cycles of power. Curator: Precisely! This allows me to consider it in the broader canon of colonial and post-colonial cultural representations in art history, inviting discourse on issues of displacement. Editor: Fascinating how the interplay between formal qualities and context can radically transform our interpretations! Curator: Indeed.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.