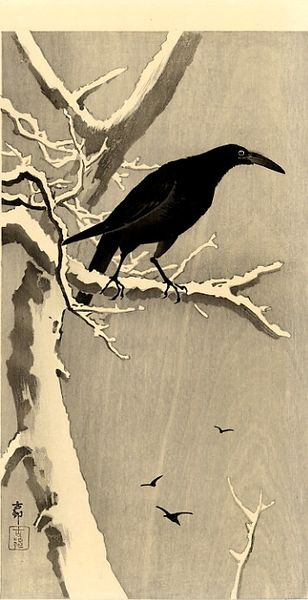

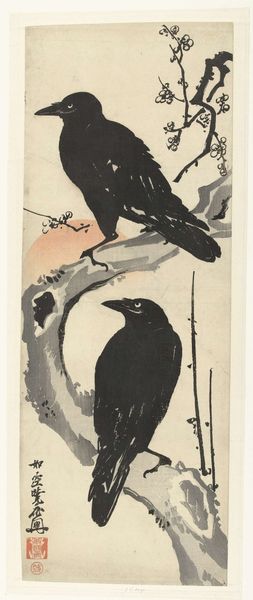

Dimensions: height 424 mm, width 268 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

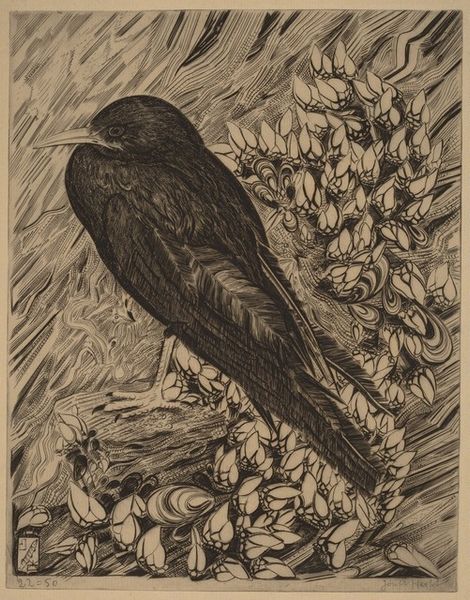

Curator: Here we have "Crow on Snowy Branch" by Ohara Koson, a Japanese woodblock print created sometime between 1900 and 1945, and part of the Rijksmuseum's collection. Editor: There's a stark beauty to it. It’s a cold, lonely image; that grey backdrop really pushes that feeling forward. Curator: Koson was a master of *kachō-e* – bird-and-flower prints. But thinking about this work’s materiality, the labour required to create the woodblocks, to mix the inks precisely for the varying greys, speaks to a whole network of production. Ukiyo-e prints, like this, weren’t merely art objects; they were products, made for consumption, distributed widely. Editor: Precisely, and beyond the artistic merit, understanding its context as Ukiyo-e allows us to see it within a broader cultural and societal framework. This print reflects both the beauty and harshness of the natural world but may mirror societal hierarchies present during the rise of Japonisme too. Was Koson subtly commenting on power structures with the lone crow as a defiant, vocal symbol? Curator: An interesting reading! But I wonder, considering the multiple blocks that would have had to been carved and inked to create that subtle shading, did Koson truly possess complete control over the final image? Or was it also reliant on the skills and interpretations of the artisans involved? The means of its production really shape how we should engage with its meaning, beyond individual interpretation. Editor: True, that artistic vision may have been mediated and negotiated. It reflects a common element within craft economies—where a singular "genius" gives way to a process deeply shaped by collective labor, gender, class and race, each carving adding to that narrative. And in the West, the arrival of these prints reshaped artistic movements, challenging perceptions about authorship and influence and creating a demand for 'exotic' prints. Curator: Right, so whether read for its subject, or the materials employed in the printmaking, it can also reflect larger artistic, economic, and social shifts in the world at the turn of the 20th century. Editor: Absolutely. It underscores the power of viewing artworks as both reflections of a specific time and active participants in larger conversations that intersect across race, labor, gender, identity, class, and history.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.