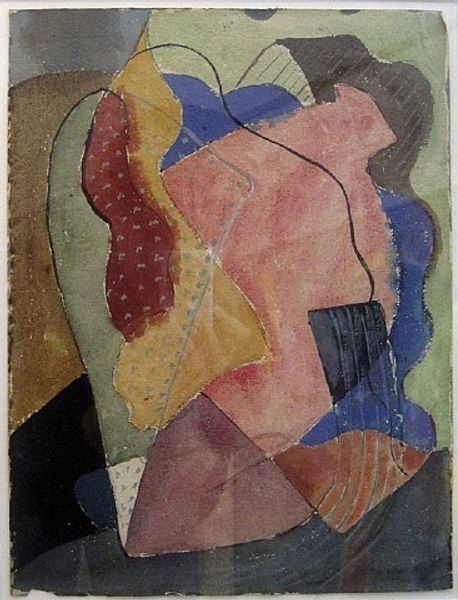

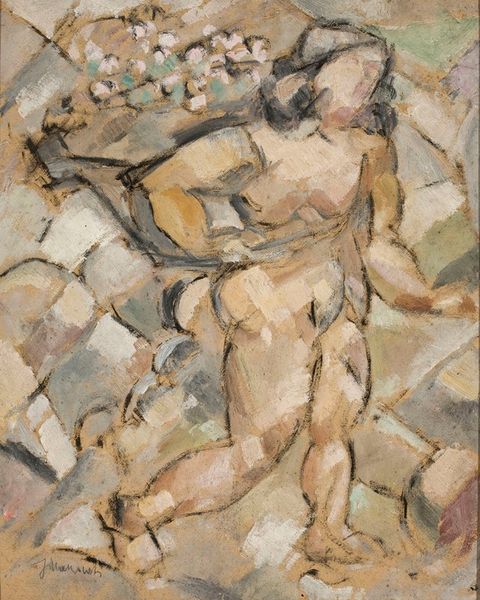

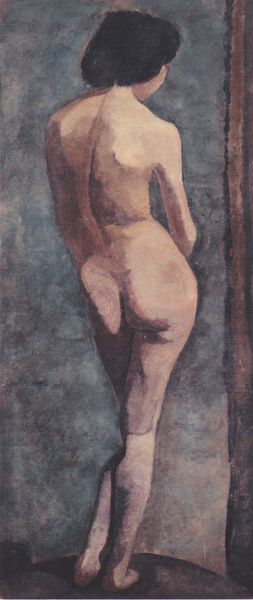

painting, oil-paint

#

portrait

#

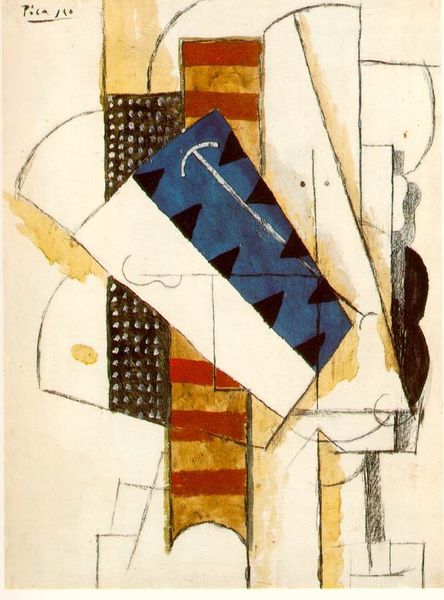

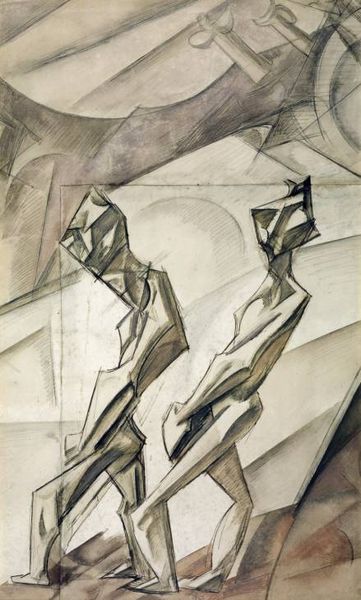

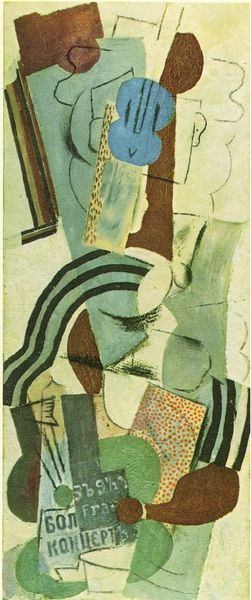

cubism

#

painting

#

oil-paint

#

figuration

#

oil painting

#

modernism

Copyright: Public Domain: Artvee

Editor: This is Walter Kurt Wiemken's "Harlequin," painted in 1925. It's oil on canvas and feels both playful and a little unsettling with its geometric, almost disjointed figure. What do you make of this depiction of a Harlequin, considering the time it was made? Curator: Well, traditionally, Harlequins are figures of mirth, of sly commentary. But Wiemken presents us with a Harlequin drained of overt joy. Painted in 1925, after the devastation of the First World War, this skewed perspective might reflect the widespread disillusionment felt throughout Europe. Editor: Disillusionment... so the painting speaks to a bigger socio-political sentiment? Curator: Precisely! The distorted cubist style, already a visual language of fragmentation, amplifies that sense of societal fracture. It's no longer about celebrating wit, but acknowledging a deeper societal wound. Note how the muted colours contrast sharply with traditional Harlequin costumes - where does that take your thoughts? Editor: I guess that the grey palette makes the character feel melancholic instead of celebratory, as if he is embodying sadness more than playfulness. Considering the context of post-war art as a way to deal with trauma, would it be right to read this Harlequin as a visual comment on societal instability and a reflection of trauma in a world where pre-war paradigms had crumbled? Curator: Absolutely. Wiemken's work can be seen as part of a larger trend within Modernism of using art to process and respond to collective trauma. It forces us to rethink familiar symbols, challenging the viewers to confront a new, uneasy reality. Editor: I never thought of art as a reflection of collective sentiment, and now I appreciate how it acts as a cultural mirror. Thank you for that enlightening perspective. Curator: It was my pleasure. The social commentary aspect enriches art, allowing it to echo human sentiment during different times.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.