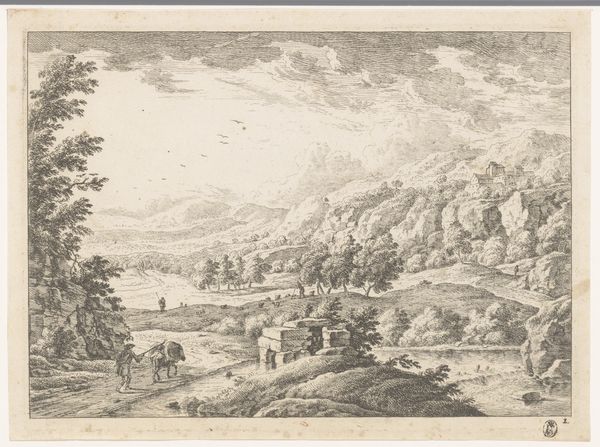

Monastery of San Francesco di Civitella in the Sabine Mountains 1810

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, etching, paper

#

drawing

#

narrative-art

# print

#

etching

#

landscape

#

classical-realism

#

paper

#

romanticism

Dimensions: 151 × 213 mm (image); 165 × 222 mm (plate); 210 × 276 mm (sheet)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: This etching by Joseph Anton Koch, created around 1810, is titled "Monastery of San Francesco di Civitella in the Sabine Mountains," and it’s a part of the Art Institute of Chicago's collection. What stands out to you initially? Editor: There’s a striking stillness to the entire scene, despite the small figures placed within the landscape. The crispness of the lines really draws me into the spatial relationships—the foreground figures against the receding monastery and distant mountains create an intriguing effect. Curator: Yes, and what I find fascinating is how Koch uses the motif of the monastery – and the figures inhabiting it – to engage with contemporary political discussions about the role of religious institutions in society during the early 19th century. Remember, this was a time of great upheaval with the Napoleonic wars impacting the power and status of such establishments. Editor: I can see that. The somewhat stark architectural rendering of the monastery, contrasted with the romantically wild landscape, introduces a compelling tension. Technically, the etching process allows for an impressive level of detail—especially in the rendering of the foliage. Did Koch employ a particular printing method? Curator: The etching technique allows for precisely those fine details that we see here, achieving clarity alongside depth, essential for the work's narrative elements, as it encourages reflection on how historical events and geographical locations shaped social structures. Editor: It's almost as if the composition itself—the arrangement of dark and light areas, the precise linearity of the architecture against the more fluid lines of the nature, presents a philosophical argument about the relationship between humanity and its environment. Curator: Precisely. And that's precisely where Koch succeeds—in subtly using landscape and its inhabitants as commentaries on power and legacy, mirroring and responding to larger ideological debates of the era. Editor: Well, exploring this from the view point of the lines and shapes has certainly offered me another perspective. Thanks. Curator: The pleasure was all mine. Thinking about art in broader social and historical settings really enriches my viewing experience, hopefully yours as well.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.