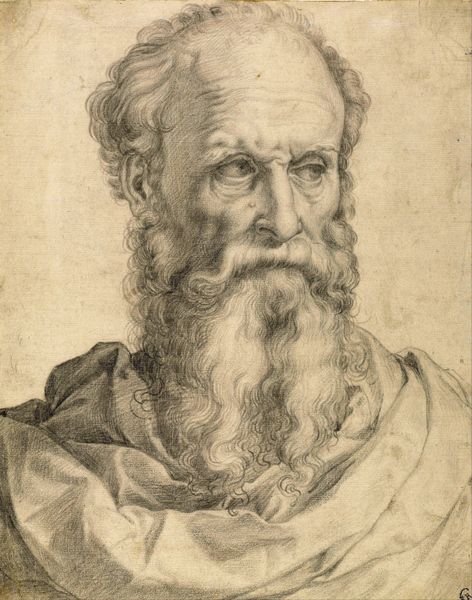

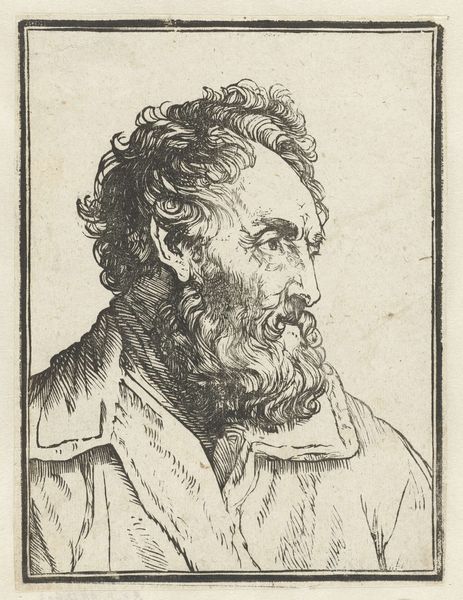

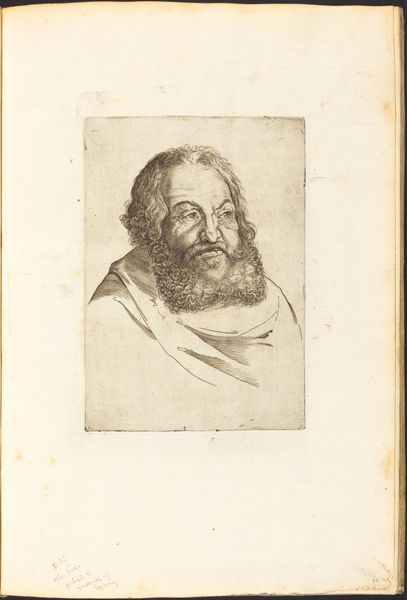

drawing, paper, pen

#

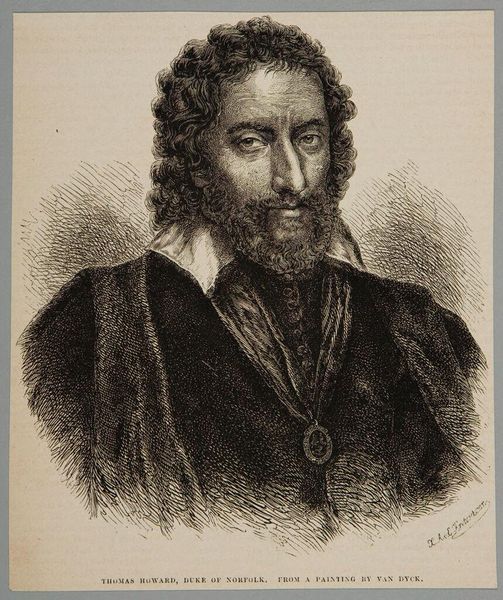

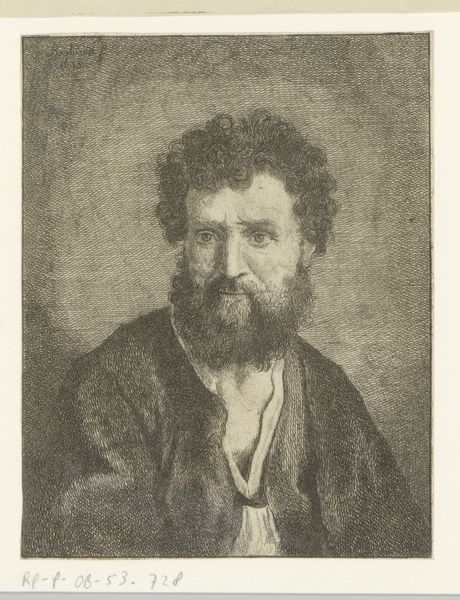

portrait

#

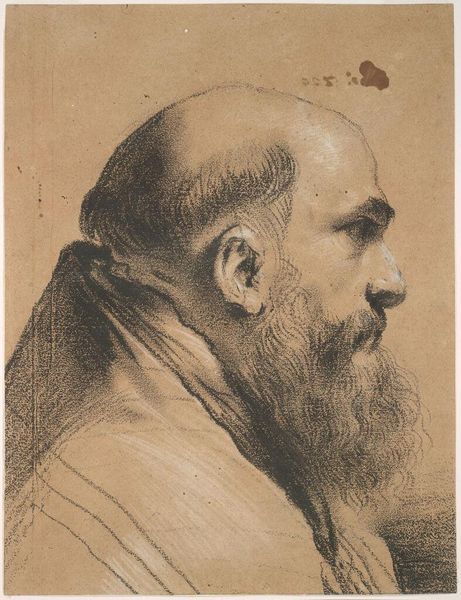

drawing

#

charcoal drawing

#

mannerism

#

paper

#

11_renaissance

#

oil painting

#

pen

#

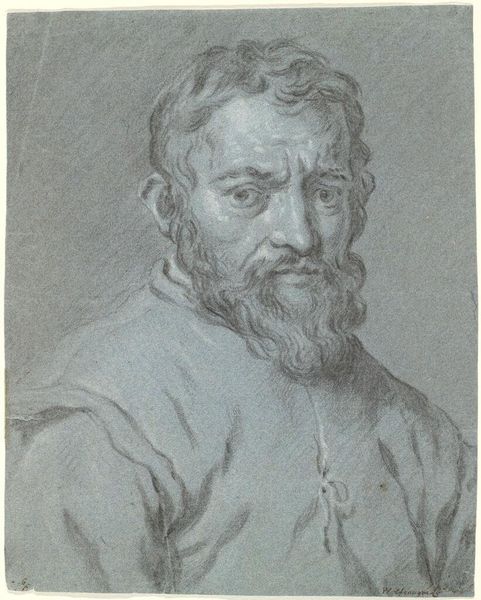

portrait drawing

Dimensions: 31 x 24 cm

Copyright: Public domain

Editor: This is Peter Paul Rubens’s “Portrait of a Man,” created around 1602, a drawing on paper using pen and charcoal. The gaze of the subject really draws me in. What do you see in this piece, beyond just a portrait? Curator: Beyond the immediate aesthetic appeal, I see a reflection of power structures and performative masculinity prevalent during the Renaissance. Rubens, while a master artist, was also deeply embedded in a patriarchal society. The subject's strong jawline and intense stare contribute to the construction of masculine authority and control in a period defined by hierarchical power. How do you think that intersects with contemporary notions of male identity? Editor: That’s fascinating. I hadn’t considered the role of the artist in perpetuating these norms. But if we view art as cultural documentation, can we separate Rubens's artistic skill from the reinforcement of these ideas about male dominance? Curator: Exactly! Separating the artist from their historical context is impossible. Rubens's artistic brilliance is undeniable, but his work, consciously or unconsciously, echoes the societal values of his time. This brings to light a critical discourse about the portrayal of masculinity throughout history. Consider how race and class also shaped access to such powerful depictions. It leads to challenging conversations. What are your thoughts on that? Editor: So, viewing art, especially portraiture, becomes an exercise in decoding not just the image but also the cultural and social context that produced it. It’s almost like archaeology. Curator: Precisely! And in doing so, we gain a deeper understanding of the power dynamics that have shaped, and continue to shape, our world. This understanding is not just about the past, but about the present. Editor: That gives me a lot to think about, viewing this not just as a portrait but a record of a particular type of power. Curator: Indeed. And questioning that power. That’s the real work.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.