Dimensions: height 198 mm, width 290 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

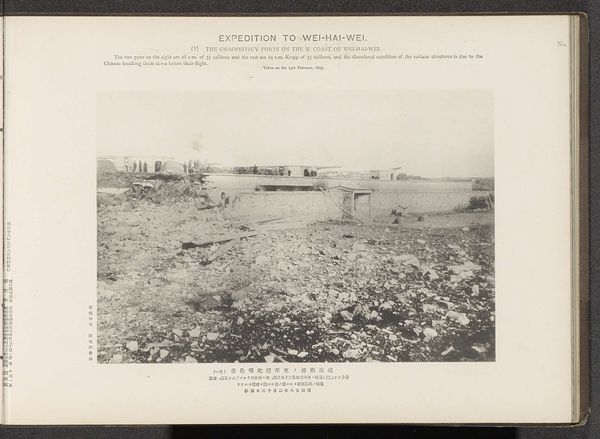

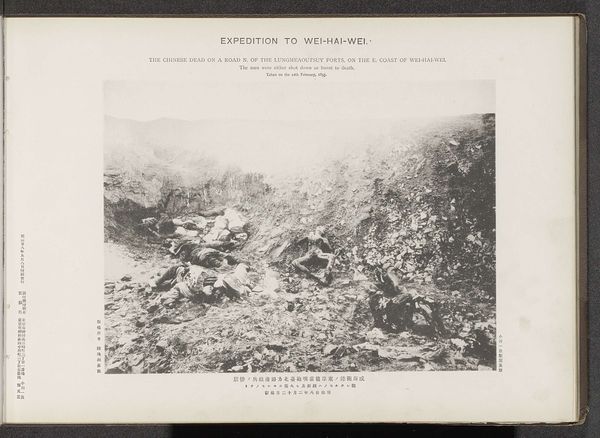

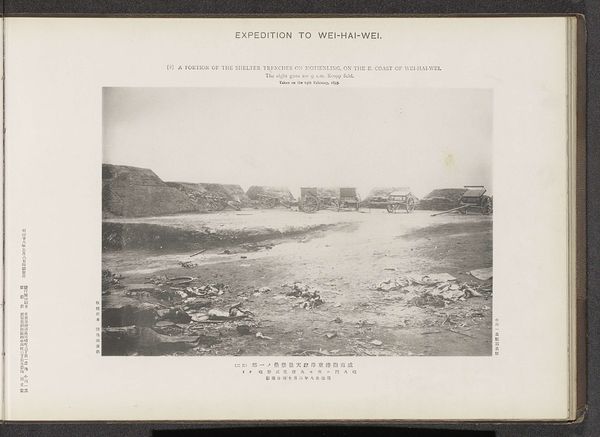

Editor: This photograph, "The Chaopeitsuy forts on the E. coast of Wei-Hai-Wei," possibly from 1895, depicts a scene of devastation. It’s incredibly stark; the black and white tones emphasize the destruction. What do you see in this piece, beyond the immediate impression of ruin? Curator: The image resonates deeply as more than just a depiction of physical damage. Consider the power dynamics at play here. It's vital to look beyond the immediate visual of the print itself to understand it as an Orientalist artifact. This photograph normalizes Western imperialism by showcasing a landscape violently impacted by colonial military intervention in China. How does that lens change your interpretation? Editor: It shifts the focus from the damage itself to the power structures that caused it. It's no longer just about the ruins, but about the act of ruin. Curator: Precisely. We have to think about whose perspective is privileged. Who is behind the camera? Who is producing and consuming this image? This photograph circulated back in Europe to feed narratives of Western progress. I wonder, what does the destruction of a place represent in terms of erased cultural heritage? Editor: I hadn't considered the lasting effects. It represents loss, doesn't it? The loss of not only physical structures, but also of history, identity, and agency. It really drives home how visual documentation can be a tool of domination. Curator: It certainly can. Images like these shaped perceptions and justified colonial policies. I'm left contemplating what strategies we can adopt in art history to resist such perspectives when engaging with archival material. Editor: This conversation has pushed me to question the narrative and dig deeper into the context. It is really impactful when looking through a decolonializing framework. Curator: I think we both came to new conclusions!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.