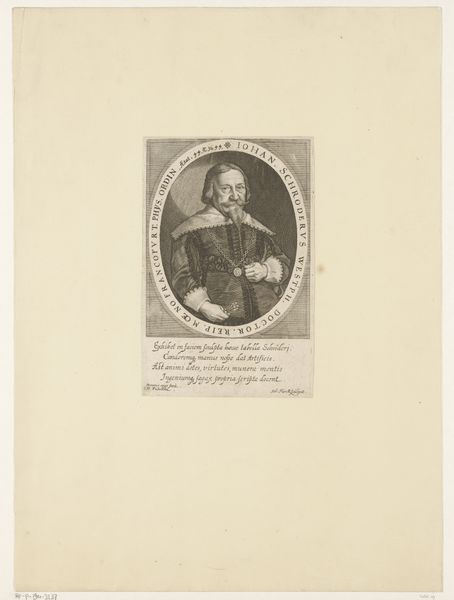

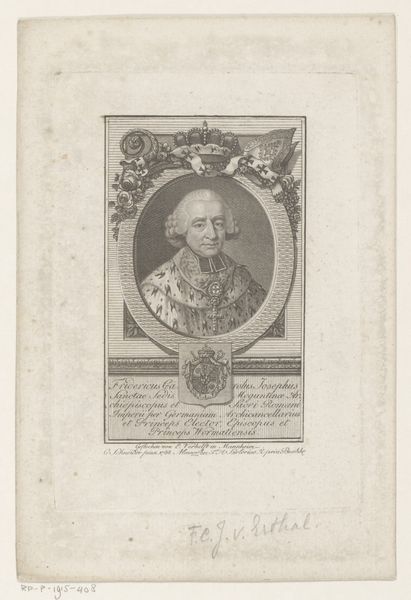

engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

#

old engraving style

#

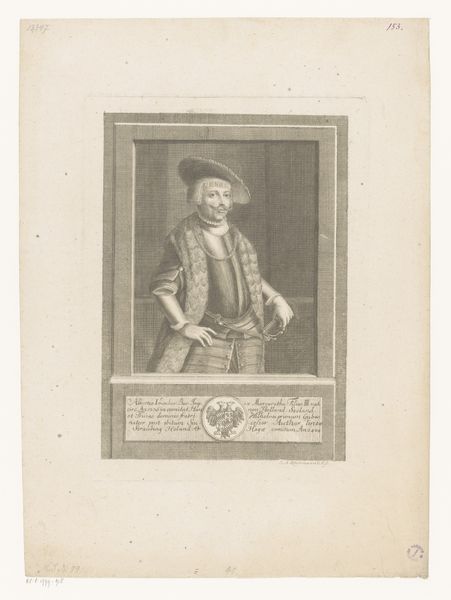

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 131 mm, width 100 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This is a portrait of Ferdinand van Brunswijk-Lüneburg, dating roughly between 1731 and 1769. It's an engraving by Christian Fritzsch and is held here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: Immediately striking! There’s such an imposing weight to this piece, even in the miniaturized engraving format. He seems rather stiff, but ornate. I’m immediately curious about how representations like this solidified power. Curator: Exactly. Let’s delve into the making of this image. An engraving meant mass production. Fritzsch's use of this method democratized Ferdinand's image. We need to think about the economic dimensions: who could afford these engravings? What kind of labour went into their making? Editor: And what narratives were being consumed along with them? Ferdinand, the subject, exists at an intersection of politics and militarism during the European Enlightenment. His role in the Seven Years' War, his connections to the Prussian monarchy...all layered within an era of shifting alliances and colonial expansion. The portrait almost seems like propaganda. Curator: In a way, yes. The print is an artifact of power made for consumption. How the engraver used etching tools, inks, and paper mattered significantly in delivering propaganda for social manipulation. Editor: Beyond manipulation, representations such as this have long been tools of visibility. In our current political climate, images operate in a similar manner, underscoring representation within our discussions of gender and identity. Who has the privilege to have their stories and portraits elevated and disseminated, then and now? It brings up pressing issues. Curator: This engraving allows us to unpack this further. From a material point, examining who the publisher of this image was could reveal the circulation networks through which power was distributed and maintained. A portrait of an individual actually can speak to larger social infrastructures, if one follows the materiality. Editor: Agreed. Considering Ferdinand's presence against broader cultural narratives certainly expands our understanding. Looking closer, we might unveil how systems of oppression were bolstered and also perhaps resisted through visual mediums, however subtle. Curator: Ultimately, it's through considering this artwork not only as a representation of a man but also as a product of specific material conditions that we see it revealing dynamics from its historical context to present-day dialogues. Editor: Exactly, prompting us to examine not just what is depicted, but how and why certain individuals and ideals were—and continue to be—privileged through representation.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.